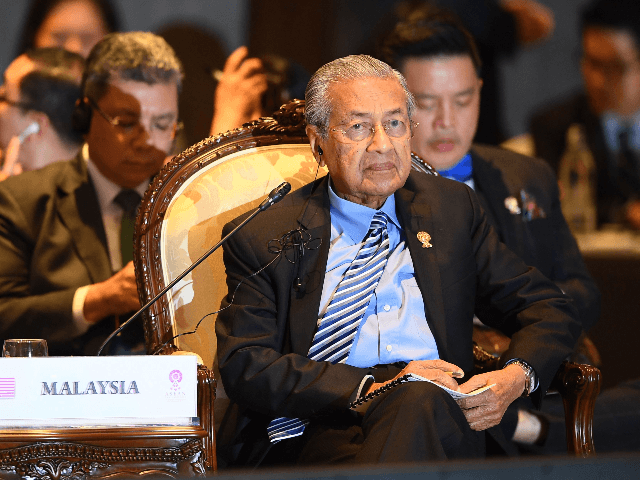

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, who returned to power at the age of 92 in 2018 with a surprise election victory over his former protege Najib Razak, made an equally stunning departure on Monday by resigning his office without warning or explanation.

Mahathir has agreed to serve as interim prime minister at the request of Malaysia’s king until a replacement can be sworn in.

The prime minister’s surprise resignation left Malaysia in turmoil by shattering its dominant political alliance, as the Wall Street Journal reported on Monday:

Neither the prime minister’s office nor Mr. Mahathir’s political party, Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia, known as Bersatu, provided a reason for the abrupt resignation. Earlier in the day, Bersatu’s president said the party was pulling out of the ruling coalition amid reports of internal turmoil in the party.

The messy developments left the alliance—which won an astonishing election victory in 2018 and promised to shift the course of Malaysian politics—in tatters. “The fact that this coalition has collapsed is one thing, but the fact that it’s collapsed in the way that it has, full of all of this drama and uncertainty and a lack of clarity, sends a lot of shock through the system,” said Bridget Welsh, a University of Nottingham Malaysia honorary research associate.

The 2018 polls marked a watershed moment because Mr. Mahathir’s Alliance of Hope defeated the United Malays National Organization that had dominated politics in Malaysia since independence in 1957. The outcome represented a democratic transfer of power in a region where authoritarianism and one-party rule have persisted. The coalition ousted former Prime Minister Najib Razak, who is on trial over a financial scandal involving the theft of billions of dollars from state investment fund 1MDB.

The diverse coalition included Mr. Mahathir’s political rival, Anwar Ibrahim, a former protégé he shares a complicated relationship with. Mr. Mahathir ruled Malaysia for years through the 1980s and 1990s, with Mr. Anwar serving as his deputy for some of that time. Mr. Mahathir fired Mr. Anwar after the two disagreed over how to handle the Asian economic crisis of the late 1990s. Mr. Anwar was then jailed for sodomy—a charge he has long denied.

The only sign of trouble over the weekend was Anwar talking vaguely about “betrayal” on Sunday, although he might not have been talking about betrayal by Mahathir. Members of Anwar’s party spoke of opposing some sort of “conspiracy” aimed at bringing Mahathir down, while Anwar himself said Mahathir resigned because he was insulted by accusations that he was secretly planning to abandon his current allies and form an anti-corruption alliance with the opposition parties he defeated in 2018.

“I appealed to him on behalf of Keadilan and Pakatan, that this treachery could be dealt with together, but of course he’s got a different mind,” Anwar said on Monday, telling reporters he had begged Mahathir to stay.

“He thought that he shouldn’t be treated in that manner, to associate him in working with those we believe are blatantly corrupt,” Anwar said of the rumors that Mahathir would be pressed into a partnership with the opposition.

Other theories suggest Mahathir resigned because he did not wish to complete a pre-election deal he made with Anwar to transfer power to him. Longtime observers of Malaysian politics described Mahathir as a clever strategist and wily survivor who might even have staged his resignation in a bid to consolidate power, potentially returning as prime minister in a few weeks with a different governing coalition, cabinet, and policy agenda.

AFP’s sources indicated rivals within Anwar’s party were working with opposition politicians to cut Anwar out of the ruling coalition and form a new government around Mahathir, who either refused to go along with it or resigned because he was involved in the plan but could not politically survive the embarrassment of getting caught while trying to undermine Anwar’s much larger party.

Mahathir’s Bersatu party vowed personal loyalty to him and withdrew from the governing coalition on Monday. Two ministers were dismissed from Anwar’s People’s Justice Party, prompting nine lawmakers to resign from the party in solidarity and announce they would form their own independent parliamentary bloc. Anwar angrily denounced “traitors” within his own party and Bersatu for scheming to bring down the government and sabotage the ruling coalition.

If Mahathir’s resignation sticks, a possible successor would be Deputy Prime Minister Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, who would become the first female prime minister of Malaysia.

According to sources inside Anwar’s party, Wan Azizah will soon be named interim prime minister because none of the competing coalitions in parliament have enough muscle to form a government. In theory, any lawmaker who can muster enough votes could become prime minister, pending the approval of the king. If no one can bank the necessary number of votes and secure royal approval, new elections would most likely be held. There is no strict upper limit on how long an interim prime minister can govern, and few limitations on their power compared to a full prime minister.

Ironically, one of the reasons Mahathir’s governing coalition was on shaky ground with Malaysian voters was the difficulty of attracting investment to Malaysia because competing nations in the region are seen as more politically stable. Malaysia’s stock market hit an eight-year low after news of Mahathir’s resignation broke, with anxiety about the coronavirus epidemic and attendant reduced business from China seen as a contributing factor in ending the longest bull run in the world.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.