On January 9, President Trump pitched the idea that NATO could take on a new and larger role: “I think that NATO should be expanded, and we should include the Middle East.”

That is, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, centered in Europe, should now become NATO + ME for Middle East, or NATOME, to be pronounced “nay-TOE-me.” It’s an interesting idea, albeit still a bit fuzzy—and it won’t be easy.

In fact, since World War Two, several attempts have been made to create some sort of Middle Eastern alliance, and they’ve all fizzled. For instance, back in 1955, U.S. diplomats working with a friendly government in Baghdad helped hammer out the Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), including Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. The hope back then, of course, was that METO, like NATO, would oppose Soviet expansion.

Yet just three years later, Iraq withdrew from the organization, which then changed its name to CENTO. Still, by any name, the organization failed to flourish; it withered, becoming ever more irrelevant, until 1979–when it finally dried up and blew away.

For their part, Arab nations have also had ideas for new alliances and arrangements. In 1958, Egypt and Syria joined together to create the United Arab Republic (UAR); the hope was that other Arab nations would join in, thereby fulfilling the dream of Pan-Arabism. But it was not to be—the UAR fell apart in 1961.

In the following decades, eccentric Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi had dreams, at various times, of a larger union of Arab and African peoples. But he couldn’t sell them to anyone—and in 2011, he himself was killed by his own people.

Meanwhile, in 1981, six Arab nations, along the Persian Gulf, created the Gulf Cooperation Council. And the GCC, while small, has at least managed to stay in existence.

Another Middle East coalition of a kind was created by President George H.W. Bush in 1990-91. This was the coalition aimed to expel Saddam Hussein’s Iraq from Kuwait. In a tour de force of diplomacy, Bush and his secretary of state, James Baker, managed to pull together 34 countries—including such key Arab states as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Syria—to follow the American lead in rescuing Kuwait.

Soldiers of the allied coalition carry their national flags past the reviewing stand and President George H.W. Bush in Washington on June 8, 1991 during the National Victory Parade following the first Gulf War. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds)

In the wake of the successful Desert Storm operation—in which the U.S. accomplished the mission of liberating Kuwait but wisely resisted the temptation of conquering Iraq—Bush and Baker hoped that some sort of “New World Order” would emerge. And yet that was not to happen, either on a global basis or a regional basis.

In the Middle East, the Arab countries were just too fractious; they disagreed over Israel, and perhaps even more profoundly, they were split between the Sunni and Shia branches of Islam.

Bush’s Not-So-Great War on Terror

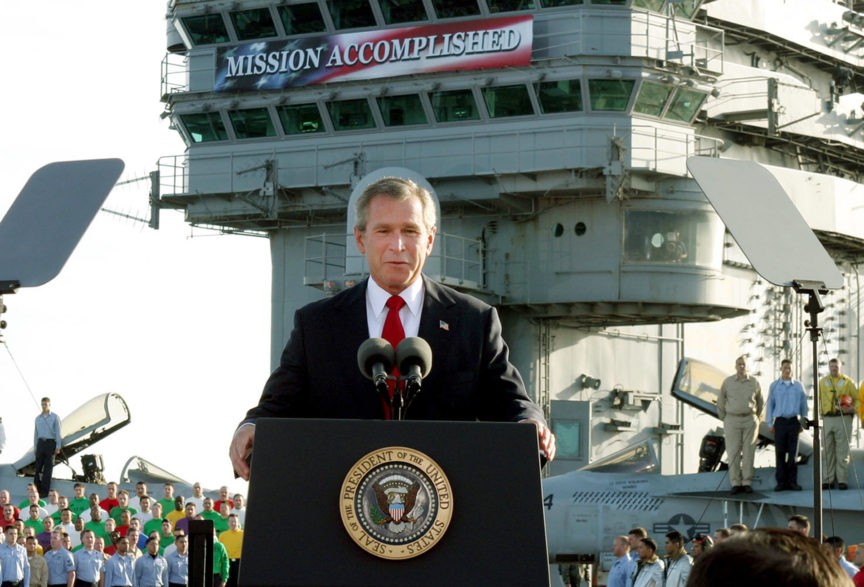

Then, in 2003, President George W. Bush attempted to create another alliance for the purpose of regime-changing Iraq. Famously, Bush did not know the difference between Sunni and Shia–the distinction between the two groups is central to any understanding of Iraq, past, present, or future.

Despite such basic geopolitical ignorance, the U.S. plunged in anyway, launching the spectacularly misnamed “Operation Iraqi Freedom” Although a fair number of countries joined the effort, at least at first, the major states of the world were all opposed to Bush’s war, as was the United Nations. In other words, the U.S. was essentially alone in a complicated geopolitical struggle; as this author has argued, it’s almost impossible to succeed when alone.

Predictably, therefore, the Iraq War was a quick military success and a prolonged political failure; instead of being greeted as liberators, we were resented as conquerors, and so the easy victory against Saddam’s obsolete military turned into a quagmire against crafty (and Iran-backed) guerrillas.

On May 2, 2003, President George W. Bush stood aboard the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln under a giant “Mission Accomplished” banner and declared that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended,” just six weeks after the invasion. The war dragged on for many years after that. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

In fact, since 2003, Arab Iraqis have been trying, militarily and politically, to be rid of the United States—the latest attempt coming just on January 5, when the Iraqi parliament asked us to leave. (The U.S. has said that it intends to stay in Iraq, although obviously that’s not a sustainable position, barring a change of heart by the Iraqis.)

The Enduring Need for a Strong Alliance

Still, Arab leaders realize that if their 13 countries—from Morocco on the Atlantic Ocean to Oman on the Indian Ocean—remain small and divided, they will be easy pickings for some larger, and even more fearsome, interloper than the U.S., be it Iran, Russia, or China.

Moreover, there’s another ray of hope for a possible Middle East alliance. Arab enthusiasm for the cause of Palestinians living in Israeli territory has waned. So now, finally, it’s increasingly possible for Arab countries to cooperate with Israel; most notably, Saudi Arabia seems to be lining up with the Jewish state on key strategic issues—most obviously, countering the threat from Iran.

In fact, in May 2017, President Trump visited Saudi Arabia and talked up the idea of a Middle East Strategic Alliance (MESA), precisely as a counter-weight to the ayatollahs in Tehran. Since then, the MESA idea has been kicked around without ever formally coming into existence.

Yet perhaps that’s about to change—perhaps some Middle Eastern alliance will, finally, be created.

President Donald Trump delivers a speech to the Arab Islamic American Summit, at the King Abdulaziz Conference Center, Sunday, May 21, 2017, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

The catalyst, of course, has been Iran. Ever since the killing of Iranian military figure Qassem Soleimani on January 3, Trump, having made his point to the Iranians—don’t mess with Uncle Sam!— is now looking for a solution that both keeps Iran in check and lowers the risk of a new “endless war.”

That dual strategy suggests a course of action that both deters, and contains, the Iranians. In other words, Uncle Sam needs peace through strength.

As the Roman military strategist Vegetius observed almost 2,000 years ago, the best way to assure peace is to prepare for war. (Si vis pacem, para bellum.)

In addition to a strong military, strong alliances can help, because allies serve as a force-multiplier. That is, the potential foe takes one look at the force arrayed against him and says, “Not today.”

This permanent show of force has been NATO’s secret sauce for more than seven decades. So maybe, just as NATO protected Europe from the Soviets and Russians for many years, NATO might now be expanded to safeguard the Arab Middle East from Iran, as well as from other threats. As Trump said on January 9th, “This is an international problem.” And, of course, since Europe is a lot closer to the Middle East than America, maybe the Europeans will realize that self-interest requires them to play a larger role in promoting stability.

Indeed, Trump went further in his ambitions. “Right now the [defense] burden is on us and that’s not fair,” he said. And yet if a NATOME could be established, thus helping secure the Middle East, he enthused, “We can come home, or largely come home and use NATO.” Indeed, as soon as January 10 reports came that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was exploring with other NATO countries to see what new structures might be possible.

President Donald Trump speaks during a working lunch with NATO members that have met their financial commitments to the the organization, at The Grove, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2019, in Watford, England. (AP Photo/ Evan Vucci)

To be sure, Trump’s new goal is going to prove highly controversial—and perhaps even impossible. Most of the 29 NATO members have no enthusiasm for greater exertions in the Middle East, and one NATO member, Turkey, currently seems hostile to some NATO objectives. Moreover, French president Emmanuel Macron has declared NATO to be “dead”; he wants to see NATO replaced by a Europe-only force—thus cutting out the U.S.

Still, it’s possible that all these issues can be ironed out. And in the meantime, a few NATO countries, such as Boris Johnson’s United Kingdom and Viktor Orban’s Hungary, might wish to help somehow. So that could be at least a start for NATOME.

Of course, in the U.S., too, any expansion of NATO into the Middle East would be difficult. In fact, as we all know, the current mood is to pull back. On January 10, a week after the Soleimani killing, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives voted 224:194 in favor of a resolution opposing any further use of force in the Middle East.

Trump’s Friends Speak Out

In that vote, which was non-binding, Democrats were joined by three Republicans, including one GOPer to whom Trump pays close attention: Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida. Gaetz has been a stalwart defender of Trump on the cable news circuit, and he is obviously a future force in Republican and national politics. And so when Gaetz voted, in effect, against Trump on the anti-war resolution—that got attention, including at the White House. As Gaetz said:

I get sick and tired of people in this town acting like toughness is engaging in conflict in the Middle East. In the resolution I voted for yesterday, there was a robust articulation of self defense.

By self-defense, Gaetz means, of course, “America First”—those being words that were brought to new prominence four years ago by candidate Donald Trump. So if Gaetz is saying we should be defending the homeland, not seeking to transform the world, well, it seems a cinch that Trump is listening and quite likely agrees. In the words of Breitbart News’ Sean Moran, “Gaetz serves as another leading advocate of Trump’s America First foreign policy vision, wherein America intervenes less abroad and focuses more on rebuilding the American nation.”

In fact, with the presidential election less than 11 months away, the pressure is building to get out of the war-war rut. As everyone knows, Fox News’ Tucker Carlson has been a strong and vocal critic of “endless wars,” and, as with Gaetz, he has Trump’s ear.

Since then, a January 9 poll from USA Today found that concern about new wars, even on the right, extends far beyond Gaetz and Carlson. The survey found that by a more than 2:1 margin—55 percent to 24 percent—Americans believe the strike on Soleimani made this country less safe. And a January 12 poll from ABC News/Ipsos found similar results. Indeed, Trump’s approval rating has actually dipped down since the Soleimani strike.

To be sure, according to a January 15 poll from the Pew Center, a slight plurality of Americans support the strike on Soleimani, and yet at the same time, a majority of Americans fear that it could lead America into a new war.

Of course, the news from Iran itself is always surprising. In the wake of the revelation that the Iranian military shot down that Ukrainian passenger jet, killing 176, and tried to cover it up for days, the Iranian government was thrown on the defensive, caught in its own lies. In fact, mass demonstrations–protesting the Tehran regime, not Trump or the U.S.–broke out all over the country. In other words, there’s plenty of evidence that the desire from freedom and normalcy abides within the heart of the Iranian people, and freedom-lovers everywhere should cheer them on. So yes, this upheaval in Iran, triggered by Trump, is an encouraging development, offering the hope of vindicating Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign against the ayatollahs.

Still, after nearly two decades of slogging through the mire of war, the American people are looking away from the Middle East altogether. That is, they want an alternative to regime-changing, nation-building, and the risk of more quagmiring; that’s the hopeful new vision, of course, on which Trump campaigned four years ago. And the January 11 death of two U.S. service members in Afghanistan only underscores the public’s frustration with the continuation of the status quo.

Moreover, as this author speculated recently, Trump might do well to take a page from Richard Nixon’s political playbook in 1972. Nearly half a century ago, Nixon, having inherited a mess in Vietnam, was astonishingly tough on the enemy North Vietnamese, even as he edged U.S. armed forces out of the war.

Yet to achieve an honorable way out of the Middle East mess—at least a way out of more combat and more sacrifice—we would have to create some sort of enduring alliance that could keep the peace.

U.S. soldiers, part of the NATO- led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), walk west of Kabul, Afghanistan, in this file photo from January 28, 2012. (AP Photo/Hoshang Hashimi, File)

In fact, Trump has been musing aloud about making peace. Speaking to a rally in Toledo on January 9, he suggested that he deserved at least some of the credit for the settlement of a conflict not far from the Middle East—the decades-long feud between the African nations of Ethiopia and Eritrea. The resolution of that conflict led to the October 11 announcement that the leader of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed Ali, would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

As Trump said in Ohio, referring to those events, “I made a deal, I saved a country, and I just heard that the head of that country is now getting the Nobel Peace Prize for saving the country.” Trump added, “I saved a big war, I’ve saved a couple of them.”

NATOME

Thus we come back to Trump’s idea of NATOME—or whatever name might stick, finally, to a Middle East alliance. To be sure, one big question for any alliance, by any name, would be whether or not Israel could, or would, join in. If Israel were to be a member of NATOME, it would be one heckuva strong alliance—strong enough, most likely, to keep the peace.

If Trump could manage to create such an alliance and if it proved to be working as intended, then surely he’d deserve a Nobel Peace Prize.

Okay, given the nature of the Nobel committee—we might recall that it gave Barack Obama the prize, and then when the 44th president expanded the war in Afghanistan, there was nary a peep from the Nobelists in Stockholm—it’s unlikely that the 45th president would ever be awarded the international accolade. He is, after all, a Republican.

Yet if Trump were to create a peace-bringing alliance such as NATOME, and then be snubbed by the Swedes, he would no doubt have something to say about that. And back home, he might just have to settle for being re-elected, running on a platform of prosperity—and peace through strength.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.