The U.S. drone strike that killed the world’s most dangerous terrorist mastermind, Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force commander Gen. Qasem Soleimani, also killed Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, a prominent Iraqi militant aligned with Iran.

In some respects, Muhandis was even more important to Iran’s ambitions in Iraq than Soleimani was.

Al-Muhandis was the founder of Kataib Hezbollah (KH), the Shiite militia gang that launched a series of rocket attacks against American positions in Iraq, eventually improving their aim enough to hit a base near Kirkuk on December 27 and kill an American civilian contractor. The U.S. responded with airstrikes that killed over 25 KH members. KH retaliated by working with Soleimani to set up an alarming, but ultimately unsuccessful, attack on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad.

In 2009, Kataib Hezbollah became the first Iraqi Shiite militia to be designated a foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. government. Muhandis was also sanctioned individually as a terrorist.

KH is part of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), a coalition of mostly-Shiite, pro-Iran militias in Iraq that organized initially to fight the Islamic State. Iraq formally legalized the PMF as a wing of the nation’s armed forces alongside the army, which has for decades struggled to maintain troops well-trained enough to keep the country stable.

As with many militant leaders and terrorists, Muhandis worked under a pseudonym; the 56-year-old’s real name was Jamal Jaafar Ebrahimi. His alias translates to “The Engineer,” a nod to his degree in civil engineering. He began his career in both politics and political violence as a member of Dawa, a Shiite party opposed to Sunni dictator Saddam Hussein, who did not tolerate much in the way of opposition.

Muhandis, along with many other Dawa members, fled to Iran after Saddam crushed their movement, obtaining dual citizenship and training under the Iranian military as part of the Badr Corps, an insurgent militia. After the United States topped Saddam, Muhandis ran for office and won a seat in the Iraqi parliament in 2005.

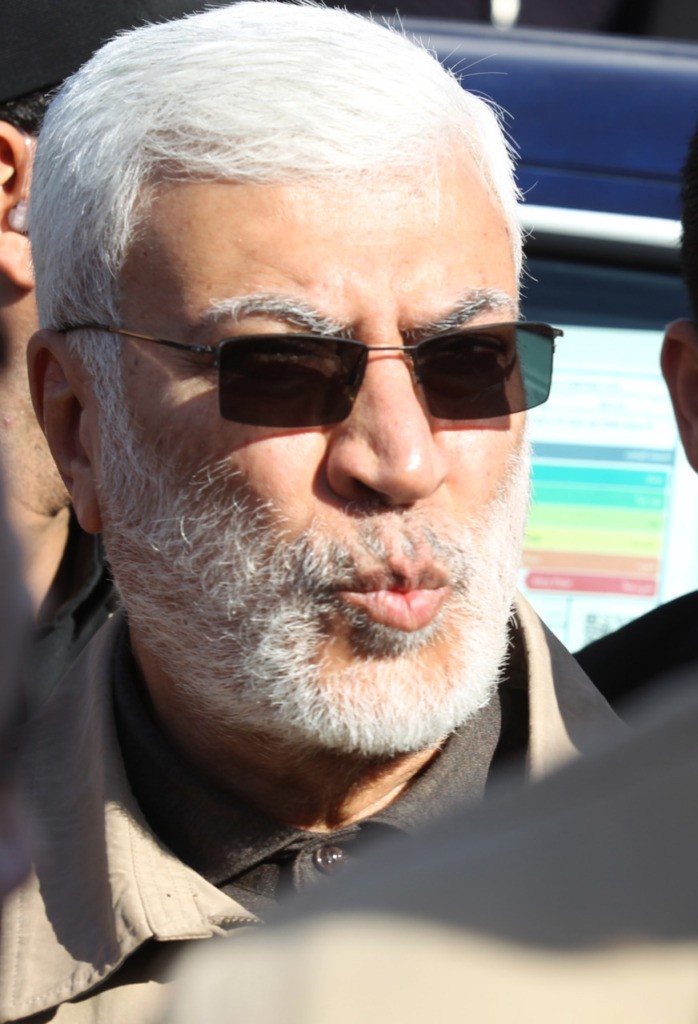

This photo taken on December 31, 2019 shows Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, a commander in the Popular Mobilization Forces, attending the funeral procession of Hashed al-Shaabi fighters in Baghdad. (AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP via Getty Images)

He eventually left that seat to resume his paramilitary career and at the time of his death was nominally the deputy commander of the PMF, also known as Hashd al-Shaabi. Many observers of the Iraqi Shiite militia scene view Muhandis as the true operational commander of the PMF, even though his title was deputy commander and he was supposedly subordinate to Iraq’s national security adviser Faleh al-Fayyadh.

Muhandis was not at all grateful to the United States for eliminating his old nemesis Saddam Hussein and making his meteoric career trajectory possible. He was a lifelong hater of America and devoted servant of Iran under a principle known as velayat-e faqih, a Shiite doctrine that essentially holds the ayatollahs of Iran as a superior authority to any national government. He was also very close to his mentor Soleimani and was happy to serve under him as an agent of Iran’s anti-American policies. He even strove to look as much like Soleimani as possible.

Like the Iranian regime he served, Muhandis had serious problems with the notion of embassies as sacrosanct foreign soil. In 1983, he was allegedly involved in planning bomb attacks on the U.S. and French embassies, plus a number of energy industry targets, in Kuwait that killed five Kuwaitis and injured 86 others. The actual bombers were Lebanese, another illustration of how Iran uses its terrorist proxies in numerous countries to carry out its dirty work. Muhandis also allegedly tried to assassinate the emir of Kuwait in 1985.

A Kuwaiti court sentenced him to death in absentia under his real name, a detail brought up by the Bush administration when it objected to Muhandis taking a seat in the Iraqi parliament in 2005.

Muhandis founded Kataib Hezbollah after he was elected to the Iraqi parliament, with the express goal of working with Iran to plant roadside bombs and carry out ambush attacks of American troops. They soon branched out into kidnapping, torturing, and murdering Iraqi civilians who opposed Iran’s agenda. A sizable number of their victims were children.

In a January 2017 interview, Muhandis said Kataib Hezbollah was working closely with Lebanese Hezbollah, which he said played a “central” role in organizing “resistance cells against the Americans” by sending fighters to bolster their ranks. He saluted both Lebanese Hezbollah and Iran for providing him with weapons. He stated that the government in Baghdad was fully aware of Lebanese Hezbollah’s participation in his operations.

In August, Muhandis accused the United States of working with Israel to coordinate secret attacks against his forces, including Israeli drone strikes staged out of Azerbaijan to strike targets in Iraq.

In his final days, Muhandis worked side-by-side with Soleimani to plot the murders of hundreds of Iraqi protesters, who were furious that the committee established by Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi did not name Muhandis as a key figure in the brutal crackdown. According to Iraqi police and security officials, Soleimani and Muhandis “hijacked” the government’s effort to deal with the protesters and turned it into a bloodbath modeled on the tactics employed to suppress protests against dictator Bashar Assad in Syria. One Iraqi commander recalled Muhandis telling him to regard the protesters as if they were enemy combatants and act accordingly.

Muhandis was also personally involved in arranging the assault on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad last week and was spotted at the scene along with many other paramilitary leaders.

“The US ambassador, the Americans and their intelligence agencies must not think that they can sustain their control over their bases in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. By Allah, we will stop America and all of its Iraqi cronies, hiding in their offices,” he told supporters a few days before his death, implicitly threatening Iraqi officials who didn’t toe the Iranian line.

Like Soleimani, Muhandis will be very difficult for Tehran to replace. His personal relationship with Soleimani, connections with Lebanese Hezbollah, utter devotion to the ayatollahs of Iran, and ties to other Shiite militia leaders were key resources for developing Iran’s network in Iraq.

Muhandis was instrumental in establishing the PMF as a state-sanctioned military force that is only nominally loyal to the Iraqi state. Personal loyalty to Muhandis was important for keeping fractious militia leaders from squabbling with each other. Washington Institute analyst Michael Knights described him as the “central nervous system” of Iran’s forces in Iraq.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.