Cold War One

For a period of time, the overseas communist empire had been America’s geopolitical partner. Yet then a string of incidents suggested that maybe the partnership wasn’t so friendly after all; numerous spies were discovered in our midst, responsible for stealing some of America’s most precious strategic secrets. Moreover, a string of American witnesses came forward to offer firsthand accounts of espionage penetrations, and the dangers they posed. And so finally, it became clear to the American people, always reluctant to abandon the hope for peace and friendship, that, yes, the partnership was truly over.

Does this seem to describe the worsening relationship between the U.S. and China over the last two decades—as most Americans have gone from being hopeful that the Chinese economic miracle would lead to democratization, to being fearful of the strategic power of Big Panda?

In the year 2000, President Bill Clinton sat down with the Chinese leadership and agreed that the two countries, the U.S. and China, would enjoy a “constructive strategic partnership.” And the two presidents since Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, both mostly ignored China as they pursued other goals, such as democratizing Iraq or signing a nuclear deal with Iran. To put that another way, both Bush and Obama were mostly content to leave the warm relationship with China in place, not really noticing that China was taking our jobs, stealing our intellectual property, and growing to be more of a geopolitical menace.

This American naiveté about China has an interesting historical parallel. You see, seven decades ago, there was another warm relationship with a communist power that grew cold. That relationship, of course, was between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, back in the 1940s. Indeed, if we study the trajectory of a warm alliance that deteriorated into a cold war, we can learn some valuable lessons in strategic statecraft—specifically, how America can can keep its footing, even as the international terrain is shifting.

During World War Two, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. had been allies in the war against Germany, and then, at the tail end of the fighting, against Japan, too.

July 1945 marked the high-water mark of that alliance. That’s when the leaders of the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain met in Potsdam, Germany to celebrate the complete defeat, two months earlier, of Hitler’s regime, and to plan for the final vanquishing of Japan, which came the following month. Amidst all those high hopes, many Americans were, yes, naive about the prospect of a constructive U.S.-Soviet relationship in the postwar era.

Yet soon, clear-eyed observers—most notably, Winston Churchill, who coined the phrase “iron curtain” in 1946—saw that the Western vision of a free world was incompatible with Stalinist totalitarianism. Thus the warmth of 1945 became chilly soon thereafter, heading toward the frigidity of the Cold War.

A critical moment in that freezing came in 1948, when the Soviets blockaded truck transport from West Germany to the urban island of West Berlin, that being an enclave of two million German civilians—as well as American, British, and French garrison troops—inside Soviet-controlled East Germany.

The Russian blockade was non-violent; the Red Army simply refused to allow supply trucks to travel the 100 miles from the West German border, through East Germany, to West Berlin. This blockade was technically an act of war, and the Americans could have regarded it as such. Yet in his larger wisdom, President Harry Truman chose to respond in a clever but non-violent manner; he ordered the Berlin Airlift, flying supplies right over the heads of Red Army blockaders—who didn’t dare shoot down the planes and really go to war.

West Berlin children perched on the fence of Tempelhof Airport watch fleets of U.S. airplanes bringing in supplies in 1948 to circumvent the Russian blockade. (Henry Burroughs/AP Photo)

The Berlin Airlift was a wondrous exemplar of American Can Do. In the course of nearly a year, from June 1948 to May 1949, the Americans and their allies flew more than 280,000 flights to West Berlin, delivering more than 2.3 million tons of supplies. After a while, perhaps tired of being embarrassed by this ongoing display of American generosity and logistical virtuosity, the Soviets lifted the embargo. And so the U.S. had won a peaceful, but still signal, victory in the Cold War. (We should, however, remember the 70 American and British airmen who gave their lives in this effort, killed in crashes and other accidents.)

The Berlin Airlift showed how the U.S. could wage the Cold War, winningly yet peacefully.

In fact, West Berlin was soon the backdrop for another winning Cold War moment. In June 1963, President John F. Kennedy traveled there to deliver the stirring words of solidarity, Ich bin ein Berliner (I am a Berliner), to a cheering crowd, delighted that JFK had spoken their language. On that day, on the new electronic stage of television, the light of a brave young president glowed for all the world to see.

President John F. Kennedy, left, waves to a crowd of more than 300,000 gathered to hear his speech in the main square in front of Schoeneberg City Hall in West Berlin. (File/AP Photo)

Cold War Two

We can add that the defense of a free city against communist encroachment is not just history; it’s also happening now, in our time, as Chinese communists threaten the liberty of Hong Kong. In fact, a poignant July 16 headline in Foreign Policy reads, “Ich Bin Ein Hong Konger”—a play, of course, on the 35th president’s speech of a half-century before. As author Melinda Liu explained, “Hong Kong is turning into the West Berlin of the quasi-cold war between the West and China.”

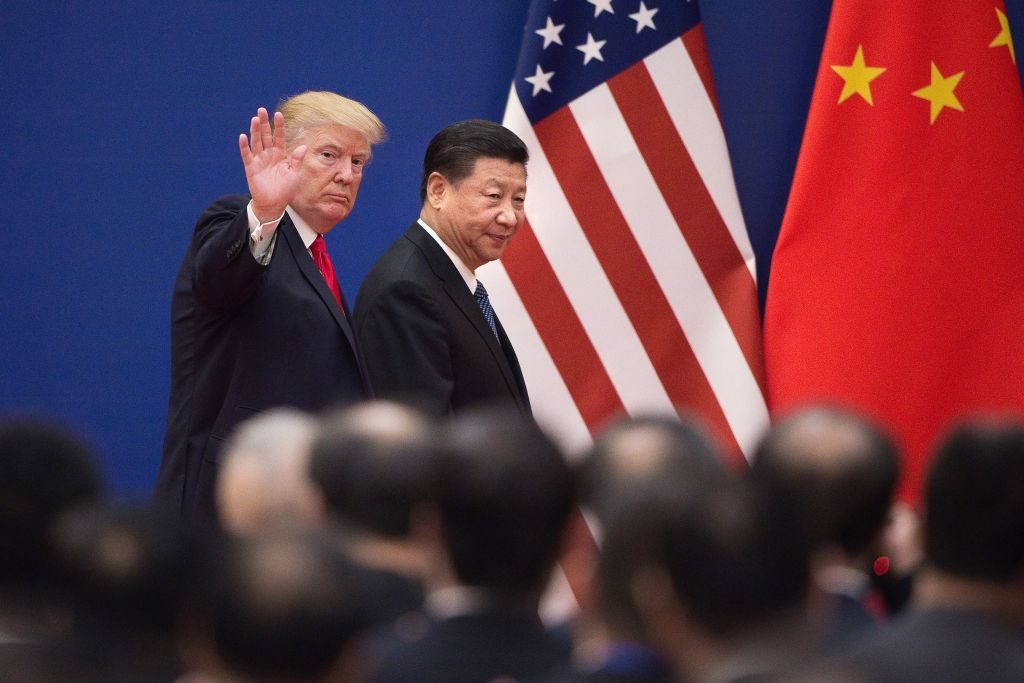

So what is the 45th president doing about Hong Kong? So far, Donald Trump hasn’t said much of anything. Why? Part of the reason is that the situation, then and now, is different; whereas West Berlin, in JFK’s day, was a sovereign non-Soviet territory, Hong Kong, in DJT’s time, is formally a part of the People’s Republic of China—and has been for more than two decades. In other words, even if he wanted to, Trump couldn’t just hop on a plane and go to Hong Kong—it’s somebody else’s country.

Moreover, Trump is currently in the midst of delicate trade negotiations with the People’s Republic. It must be noted that in world politics, the goal of preserving freedom for Hong Kong must always be weighed against all other American goals.

U.S. President Donald Trump (L) and China’s President Xi Jinping leave a business leaders event at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on November 9, 2017. (NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP/Getty Images)

Yet still, Trump has been tough on China in ways that his immediate predecessors never were. As he said of trading arrangements during the 2016 campaign, “We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country, and that’s what they’re doing.” Three years later, Sino-U.S. relations, stirred by Trump’s stark rhetoric, are in flux, and it’s undeniable that the old warmth between the two countries has cooled.

Indeed, the Trump administration is actively seeking new ways, less heralded than in trade, to slow China’s momentum. For instance, the Pentagon has taken steps to loosen China’s stranglehold on rare earth elements, needed for many advanced production processes, by expanding U.S. domestic production.

Still, plenty of Americans hanker for the “good old days” of easy trade, and no-questions-asked outsourcing to China. Just on July 23, two writers for Bloomberg News warned against a trade conflict with the P.R.C.; looking at relations through a distinctly corporate prism, the duo warned against a possible trade conflict: “The risk is such a war would leave the U.S. isolated and unable to take advantage of innovation that is increasingly cross-border.” We can observe that this familiar mantra, “innovation,” typically means that the U.S. hatches an idea, while the Chinese actually manufacture it. The end result, of course, is that the Chinese come out way ahead, as they come to possess not only the intellectual property, now shared, but also the manufacturing capacity—exclusively all theirs.

And speaking of the leakage of intellectual property, including state secrets, we can once again look back to the Cold War and find parallels to today.

Spies, Yesterday and Today

In September 1945, Igor Gouzenko, a cypher clerk in the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, Canada, defected, bringing with him abundant evidence of deep Russian penetration into the West. In fact, Gouzenko was just one of a number of defectors and refugees offering up scary details about Soviet espionage, which was aiming to pilfer everything from military plans to industrial secrets.

Indeed, Soviet agents had even managed to gain our greatest secret, the know-how for making an atomic bomb. Greatly aided by their spy rings, the Soviets exploded their own A-bomb in 1949. Bottom line: The Americans did the thinking, and the Russians did the stealing.

Yet for reasons of security—as well as, sometimes, a desire to cover up embarrassing failures—U.S. authorities chose to cloak the full extent of Soviet spying; the last major counter-intelligence secret, the Venona project, was not declassified until 1995. Only then did we learn just how many spies the Russians had placed in our midst.

Importantly, back in the ’40s, the Soviets had many American allies who were not friendly to Moscow, but yet were not actual spies. In fact, millions of Americans—some active communists, some merely left-wing fellow travelers—were eager to promote communism and, also, just as eager to discredit anti-communism. Thus anti-communist Americans, warning of Soviet dangers, found themselves derided as “imperialists,” “fascists,” and “warmongers.”

The most important of the pro-Soviet voices was Henry Wallace, a former vice president. In the late ’40s, Wallace stoutly insisted, against mounting evidence, that the Soviets were good-hearted partners for peace, and that we just needed to understand them better:

There is no misunderstanding or difficulty between the USA and USSR which can be settled by force or fear and there is no difference which cannot be settled by peaceful, hopeful negotiation.

So that was the message of the left in those days: We must go the extra mile to be friends with Stalin. Historians still debate whether Wallace was a dope, a dupe—or an outright Soviet asset. Whatever the truth, Wallace, popular with the media, was a political force to be reckoned with.

Fortunately, these pro-Soviet Americans soon met their match—actually, met more than their match. This Soviet-stopper was Whittaker Chambers, an unlikely hero if there ever was one. Chambers was a pudgy and rumpled journalist—who was, in fact, a onetime communist. Yet he had recanted Bolshevism, found Christianity, and then blown the whistle on a Washington, DC, cell of influential red spies.

The most famous of these spies was Alger Hiss, who had held high posts at the State Department during World War Two; after that, he took a cushy job as president of the liberal-leaning Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (In those days, non-communist liberals often found it hard to see the difference between themselves and communists.)

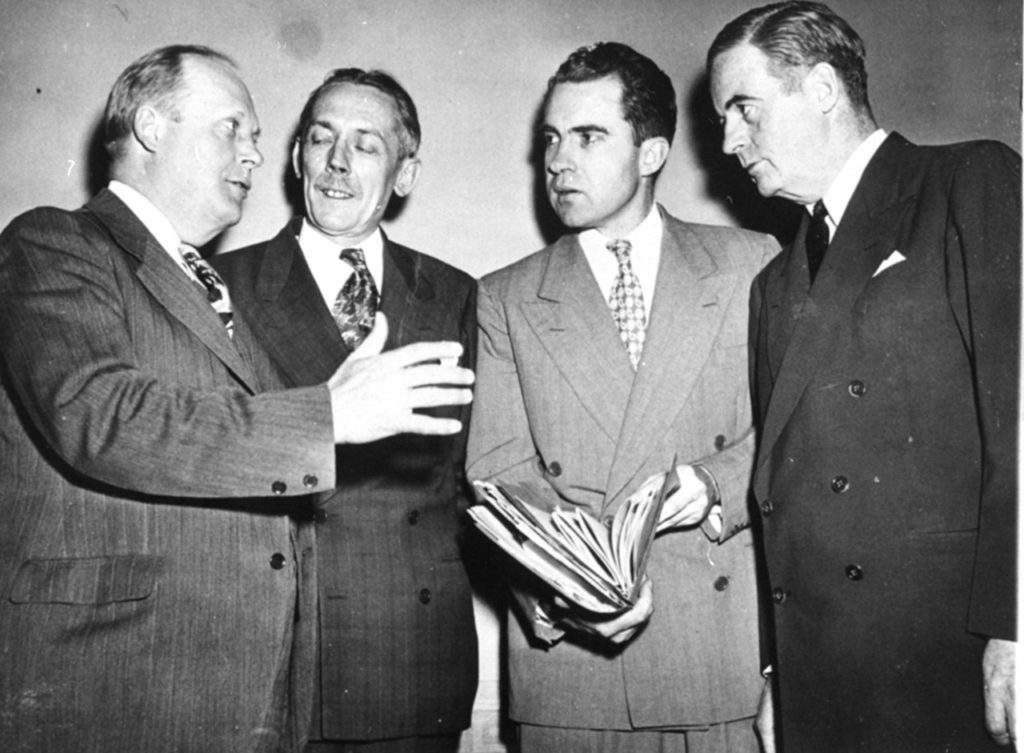

In the summer of 1948, Chambers cooperated with a rising young Republican, Rep. Richard Nixon of California. Nixon was only a freshman Congressman, just 35 years old, and yet his colleagues, taking note of his work ethic and intellect, gave him the task of steering the inquiry of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC). Guided by Nixon’s lawyerly strategizing and questioning, Chamber’s testimony proved explosive, blowing Hiss out of his posh pro-Soviet perch.

Whittaker Chambers takes his turn on the stand testifying in Washington on August 25, 1948, before the House Un-American Activities Committee. (WCA/AP Photo)

Alger Hiss, accompanied by his wife, Priscilla, arrives at Federal Courthouse in New York City on June 24, 1949, for the second day on the stand testifying in his perjury trial. (Murray Becker/AP Photo)

Soon, Chambers was a national hero to most Americans, even as the hard left, suddenly on the defensive, disdained and despised him. In the years that followed, Chambers, now forever a polarizing figure, authored a best-selling memoir, Witness, a book that stands out, even today, for its literary quality and personal honesty. Chambers was even awarded, posthumously, the Medal of Freedom.

Meanwhile, Hiss was packed off to prison.

Okay, so now, if we are to continue with the then-and-now historical parallelism, we can ask: Is there an American figure today who might be playing a role comparable to Chambers back then? Actually, there could be several.

Three Witnesses, and Maybe More

One potentially comparable figure is Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley venture-capital legend. On July 14, at a Washington, DC, conference on nationalism, Thiel took up the subject of Google’s relationship with China, asserting that it was “seemingly treasonous.”

Here we might pause to observe that unlike Chambers, Thiel was never a communist, nor a spy. And yet still, Thiel has been a witness to China’s penetration of Silicon Valley; in the decades since graduating from Stanford University, he has played a key role in the formation of numerous startups, including PayPal, Facebook, and Palantir.

Peter Thiel speaks during a discussion at the National Press Club on October 3, 2011, in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

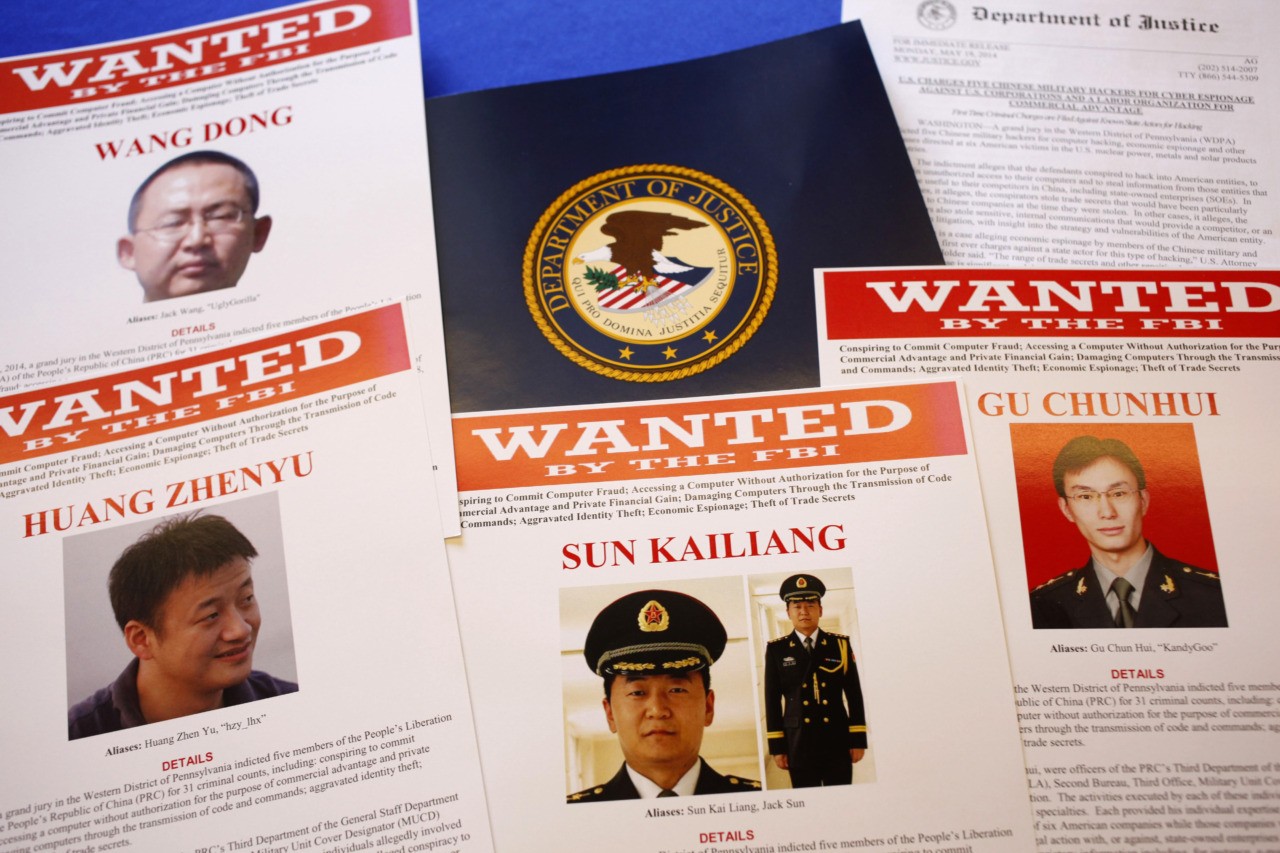

During those same decades, we might add, scores of Chinese spies have been caught in the U.S., most of them apprehended while trying to breach a tech sector.

Yet it’s worth noting that in his D.C. speech, Thiel didn’t directly accuse anyone of being an actual, premeditated spy for China; he was making a general charge, not a specific or personal one. Indeed, the point of his decision to insert the adverb “seemingly” in front of “treasonous” could have been intended to describe a situation in which people and firms were taking action against American interests, even if they didn’t quite realize it.

Yet even so, Thiel’s description of the psychology of Google, and its employees, was damning:

They consider themselves to be so thoroughly infiltrated that they have engaged in the seemingly treasonous decision to work with the Chinese military and not with the US military . . . because they are making the sort of bad, short-term rationalistic [decision] that if the technology doesn’t go out the front door, it gets stolen out the backdoor anyway.

The following day, July 15, a second witness, Joe Lonsdale, a partner of Thiel’s at Palantir—and a major venture-capital force in his own right—also stepped forward. Appearing on CNBC, Lonsdale declared:

Google clearly needs to evaluate what it’s doing. Peter and I built a very patriotic company. Google is clearly not a patriotic company.

Continuing, Lonsdale added, “Everyone in the Valley knows that the Chinese government is very involved there,” including, yes, “Chinese spies.”

Then, on July 16, a third witness, Alex Stamos, a former chief security officer at Facebook, tweeted, “It is completely reasonable to assume that MSS and SVR have subverted employees at all the major tech companies.”

We might note that “MSS” stands for the Ministry of State Security for the People’s Republic of China, and “SVR” is the spy agency for Russia.

These accusations raised alarms. Soon thereafter, Trump vowed that the Justice Department would investigate Google, and the President has since reiterated his determination to dig. (And, of course, for a variety of reasons, all of Silicon Valley is also under close scrutiny from Congress.)

The photo shows the press materials released by the U.S. Justice Department on May 19, 2014, detailing charges of economic espionage and trade secret theft against five Chinese military officers, all hackers in an international cyber-espionage case. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

Hanjuan Jin, enters the federal courthouse Wednesday, Aug. 29, 2012, in Chicago, before being sentenced to four years in prison for stealing trade secrets from Motorola Inc. for the Chinese military. Jin, who worked as a software engineer for Motorola Inc., was stopped by U.S. customs officials in February 2007 as she was attempting to leave the country on a one-way ticket to China carrying over a thousand confidential Motorola documents. (AP Photo/M. Spencer Green)

Needless to say, just as in the ’40s, the anti-communist witnesses faced pushback. Typical was Business Insider, which sniped, “The verbiage of ‘patriotism’ and ‘treason’ among tech moguls is new and alarming, reminiscent of the McCarthy era in 1950s America.”

We can step back and observe that to most Americans living in the ’40s and ’50s, those years were a time when dangerous communist influences in America were exposed and curbed. And yet to some Americans, including many in the media, the ’40s and ’50s were a dark time of repressive “McCarthyism,” in which many communists were denied such jobs, such as screenwriting for Hollywood.

The New York Times, always the agenda-setter for the left, made clear where it stood in a July 20 story headlined, “A New Red Scare Is Reshaping Washington.” So we can see: Just as it did in the ’40s, the Times strongly disapproves of too-vigorous anti-communism. (Moreover, if Trump is anti-China, then it’s easy to see how a correct-thinking progressive would feel compelled to be pro-China, at least in relation to the U.S.)

In that piece, the Times quoted Susan Shirk—a top State Department official in the Clinton administration, now chair of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California at San Diego—as saying that the U.S. was now, lamentably, gripped by “an anti-Chinese version of the Red Scare.” Shirk added, “We’ve made this mistake once before, during the Cold War, and I don’t think we should make it again.”

So that’s the progressive line: The anti-communism of the ’40s and ’50s was a mistake, and we shouldn’t make that mistake again today.

So now the question: Will Thiel, Lonsdale, and Stamos be called to testify before Congress, as was Whittaker Chambers back in 1948? If so, their testimony could crystallize public understanding of the new communist threat. Or if not any of that courageous trio—Thiel, Lonsdale, and Stamos—perhaps other patriotic witnesses might come forward? Silicon Valley is, after all, a large place, and this is, after all, the Information Age, and so there should be no shortage of information about Chinese activities.

Sadly, the House Un-American Activities Committee no longer exists; in Cold War One, it proved to be a fine forum for the airing and debating of important topics. And yet HUAC could always be revived; interestingly, the origins of HUAC reach back to 1918, when a predecessor committee was launched by Democrats.

We might also add that one reasons why Chambers’ appearance before HUAC proved so effective was that it came in the wake of a thorough investigation; in other words, Chambers’ testimony was only the clincher, because plenty of spadework had already been done.

One key digger, in particular, deserves to be remembered. That was Father John Francis Cronin, a Catholic priest who wrote a detailed look at Soviet penetration in October 1945—that is, just two months after the end of World War Two, when few were thinking of a possible Cold War. As Cronin documented, the communists had set up numerous front groups, mostly under the banners of progressive causes; for instance, there was the American Committee for the Foreign-Born, based in New York City, as well as other front groups, such as the Council on African Affairs and the Council for Pan-American Democracy, also located at the same Manhattan address.

Aided by Cronin and many others—including J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI—Nixon became an anti-communist hero; soon thereafter, he was elevated to the U.S. Senate, then to the Vice Presidency.

Reps. Karl Mundt, John McDowell, Richard Nixon, and Richard Vail, left to right, on May 19, 1948, discuss House passage of the Mundt-Nixon anti-communism bill. (AP Photo)

It’s worth pointing out that many Democrats, too, were strongly anti-communist back then. One such was Rep. Thomas J. Dodd of Connecticut, who was elected to Congress in 1952, after two decades of distinguished service in law enforcement; he was first at the FBI, then at the right hand of the attorney general, then also served as a prosecutor of Nazis at the Nuremberg Trials.

(As a tangential aside, it’s worth recalling that decades later, in the ’60s and ’70s, the careers of both Nixon and Dodd were waylaid by scandals unrelated to their anti-communism, although some suspected that the hostility they engendered through their sleuthing contributed to the animus against them. Still, anyone in public service should remember that having the right enemies is never an excuse for bad behavior.)

Five Lessons About Internal Security

So today, as we enter in what seems to be Cold War Two with China, what lessons about internal security can we learn from Cold War One? Here are five:

First, cold wars are preferable to hot wars. As we have seen, Truman and Kennedy, as well as other Cold War presidents, preferred to focus on measures short of actual fighting with the Soviets. The result, as we know, was a peaceful American victory; the USSR collapsed in 1991. So while of course we need a strong military, including a strong nuclear deterrent, we must strive to manage our diplomacy so that we can minimize actual combat. And we should also remember that weakness is provocative, because it becomes dangerously tempting to the foe. So that’s why internal security is always a vital form of national security, always to be safeguarded.

Second, as we recognize with pride that America’s glory is its freedom, we must also realize that our openness has made us vulnerable to nogoodniks, who would take advantage of our good faith.

Third, our vulnerability is exaggerated by new technologies, most obviously, the Internet. Yes, by now the Net is familiar, and yet even so, none of us can say that we fully understand all its implications and weaknesses. Thus we should expect that Silicon Valley companies will work with, not against, proper authorities to assure our safety, as consumers, as citizens, and as a nation.

Fourth, if the need for investigation does arise—and it will—it’s best to pick the smartest and most effective leaders, as the Republicans did with young Richard Nixon. Moreover, if possible, it’s best that these investigations are conducted on a bipartisan basis. Back in the Chambers era, plenty of Democrats, such as Tom Dodd, were on board with muscular anti-communism, and that strengthened our nation’s security.

Fifth, the struggle to preserve and protect America is larger than the fate of any one individual. That is, a particular politician may falter or fail—and will, for sure, eventually pass from the scene. So the national goal should be to transcend personality, as well as party. The mission of defending the integrity of the nation, without fear or favor, now and forever, should take precedence over any individual citizen.

If we keep these five points in mind, we can fully expect to preserve both our freedom and our internal security—no matter what the Chinese throw at us.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.