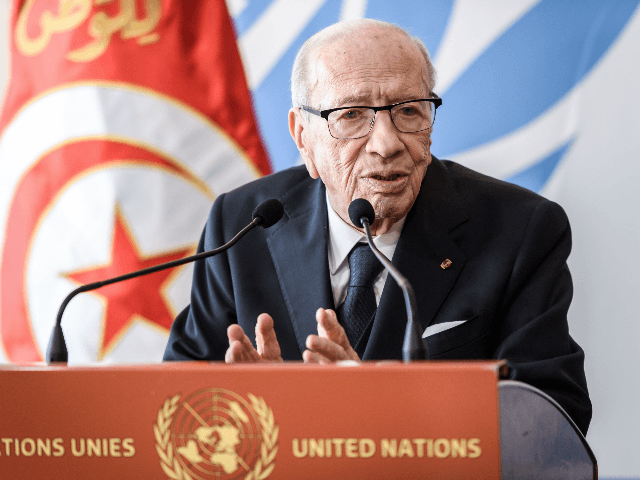

The first democratically elected president of Tunisia, Beji Caid Essebsi, died on Thursday at the age of 92. He was the third-oldest head of state in the world after Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II and Malaysian President Mahathir Mohamad.

He came out of retirement in 2011 to form a political party and win the country’s first post-Arab Spring election, and was seen as a much-needed moderate stabilizing force at a time when Tunisia might have slipped into Islamist fundamentalism.

Educated in France and trained as a lawyer, Essebsi’s involvement in Tunisian politics stretched all the way back to the end of French colonial rule in 1956, including stints as interior and defense minister for the first independent Tunisian government, headed by his political idol Habib Bourguiba. Essebsi’s services for the Bourguiba regime included putting down a military coup in 1963, which led to accusations that Essebsi abused human rights and staged show trials for Bourguiba’s political opponents.

Bourguiba wound up holding power until he was deposed by a coup in 1987 and replaced by his former prime minister, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who in turn was deposed by his prime minister Mohamed Ghannouchi in 2011. Various elections were held over the decades, but none of them was considered free or fair until the election Essebsi won in 2014. Some of the previous elections saw the opponent running unopposed.

Essebsi quickly cobbled his Nidaa Tounes (“Call of Tunisia”) party from a smorgasbord of constituencies, ranging from business leaders to left-wing academics and Islamists, after the Arab Spring kicked off in Tunisia. The event widely regarded as sparking a string of revolutions across the Middle East was an anguished fruit seller who set himself on fire after police shut him down and humiliated him for lacking a permit. President Ben Ali’s regime did not long survive the immolated fruit seller.

Essebsi and his party were able to keep Tunisia from sliding into the abysses of anarchy and Islamism that claimed the other fledgling Arab Spring democracies, although he has been criticized for backing away from democratic liberalization and attempting to set up a political dynasty.

Ironically given the economic despair and frustration with a stagnant bureaucracy that launched what Tunisians refer to as the Jasmine Revolution in 2011, the economy remains weak and unemployment is actually three points worse than it was when the fruit seller set himself on fire. Tunisia has been under constant siege from Islamists since Essebsi was elected president, with huge terrorist attacks rocking the country in 2015 and frequent battles between security forces and militants.

Essebsi’s health began deteriorating last month, leading to three stints in the hospital. The government rebuffed questions about his condition, leading Prime Minister Youssef Chahed to accuse those who said Essebsi was desperately ill of spreading “fake news.”

Essebsi had already announced he would not run for president again in the November elections despite appeals from his party, saying it was time to “open the door to the youth.” Mohammed Ennaceur, the speaker of the Tunisian parliament, is scheduled to be sworn in as interim president on Thursday, although there are some procedural issues that need to be cleared up, such as the need for a Constitutional Court that does not currently exist to formally confirm the vacancy of the presidency.

Nidaa Tounes is not doing terribly well at present. In fact, the party’s secretary-general accused Chahed of organizing a coup against Essebsi and brought charges against him at a military tribunal, paralyzing the government. Nearly half of the parliamentarians elected with Essebsi in 2014 have defected to other political factions.

Observers say the fractious Nidaa Tounes party has been cracking up practically since it was formed. Essebsi has to pass party leadership along to others when he assumed the presidency. Party meetings have dissolved into fistfights. When leadership was assumed by Essebsi’s son Hafedh, half the party denounced the attempt to establish a political dynasty.

Each half accused the other of forming unacceptable coalitions with other blocs in parliament. Hafedh Essebsi accused Prime Minister Chahed of treating Nidaa Tounes officials with disrespect and appointing cronies to replace them, while Chahed declared he was waging “war on corruption.”

How all of this will play out after the death of the respected “old wolf” Beji Caid Essebsi remains to be seen. Most observers seem to feel the Tunisian constitutional system is strong enough to weather the crisis with Ennaceur’s interim presidency firmly in place until the November election. Despite the government’s peevish answers to questions about Essebsi’s health, Tunisians were growing accustomed to the idea that he might not make it to November.

The Tunisian government declared a seven-day period of mourning for Essebsi, hailing him as one of the nation’s “greatest men and one who contributed the most to building it.” The statement celebrated him for “fighting for [Tunisia] to become and to remain free, strong, secular, and modern until the end of time.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.