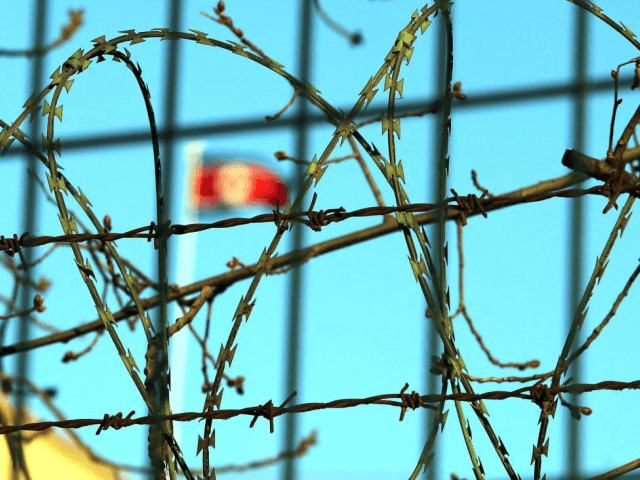

North Koreans who fled the regime and live in South Korea say the government and major national institutions are pressuring them to treat the human rights atrocities they experienced as “taboo” and to refrain from criticizing the leftist government for warming up to dictator Kim Jong-un, the South China Morning Post reported Tuesday.

The Post report is the latest in a series of similar complaints surfacing in South Korean and other Asian media that defectors and refugees who choose to speak freely about the horrors they endured in the communist country are being silenced or removed from the public eye by those who support President Moon Jae-in’s policy of rapprochement with North Korea.

South Korean authorities estimate that 32,000 North Korean refugees live in the country. Many choose to live quiet lives, fearing retribution from North Korea. Others, however, have chosen to speak out publicly about the human rights abuses they endured and the experiences they had under Kim Jong-un. Some of these tell the South China Morning Post that South Korean authorities and major media outlets have encouraged them to keep their criticism to themselves.

One of these defectors, the animator Choi Seong-guk, told the newspaper that he was essentially “kicked out” of a South Korean television studio after making the mild comment that Kim Jong-un, a dictator known to keep tens of thousands of his citizens in labor camps and approve of harrowing public executions, should not be trusted.

“They asked my opinion about Kim Jong-un’s trip to South Korea. I told them we cannot believe him as people in North Korea always say ‘peace will only come after all the capitalists in the South disappear’. We shouldn’t be tricked by Kim Jong-un,” Choi explained. “Then, the host said: ‘Thank you very much’ and kicked me out of the show shortly after. It took less than five minutes.”

Refugees have complained of this sort of censorship since April, when Seoul began expanding its efforts to raise support for Moon Jae-in’s meeting with Kim Jong-un on the Korean border, the first of its kind. One of these defectors, Ahn Chan-il, the president of the World Institute for North Korea Studies, told the newswire service UPI that he was essentially removed from South Korean television for addressing Kim Yo-jong, Kim Jong-un’s sister and believed to be the head of Pyongyang’s propaganda operation, with insufficient reverence. Ahn reportedly called Kim “that woman” on television, then abruptly watched invitations to appear on television end completely.

Ahn told UPI that “all defector interviews on television and radio have decreased by about 80 percent at least since the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics.”

Others complaining about censorship to the South China Morning Post this week included an unnamed professor who told the outlet that his academic superiors chided him for referring to North Korea as a “nuclear regime,” despite the fact that no evidence exists that the Kim regime has done away with its illegal nuclear weapons program. Several others told the outlet that they have felt pressure not to discuss human rights in North Korea when appearing publicly in the South.

The issue of human rights was notably absent from discussions in the first meeting that Kim and Moon held this year. Perhaps even worse than not being mentioned at all, it was Kim Jong-un who made note of the large refugee community, not Moon.

“North Korean defectors and displaced people do have high hopes for our meeting today,” Kim reportedly said during their talks in Panmunjom, the border “peace village” the Koreas use to hold meetings.

North Korea stands accused of a wide variety of human rights abuses under Kim and his predecessors, father Kim Jong-il and grandfather Kim Il-sung. Among the crimes attributed to the regime are the public execution of individuals caught possessing foreign media, particularly Hollywood movies; the use of labor camps to imprison any individual believed to not support the regime and their entire families, including children born in the labor camps who are not allowed to leave; the gruesome execution of officials Kim decides are insufficient loyal through methods such as anti-aircraft fire; and the forced starvation of millions through appropriating funds to the nation’s nuclear program instead of humanitarian aid.

Ji Hyeon-a, another defector who has taken on the role of human rights activist, told the South China Morning Post that she felt pressured into silence, particularly after President Donald Trump met with Kim in Singapore.

“[None of the leaders] mentioned anything about [North Korean] human rights … Trump even described Kim as a citizen-loving leader, which felt quite unpleasant,” Ji said. “It made all 32,000 defectors in South Korea liars.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.