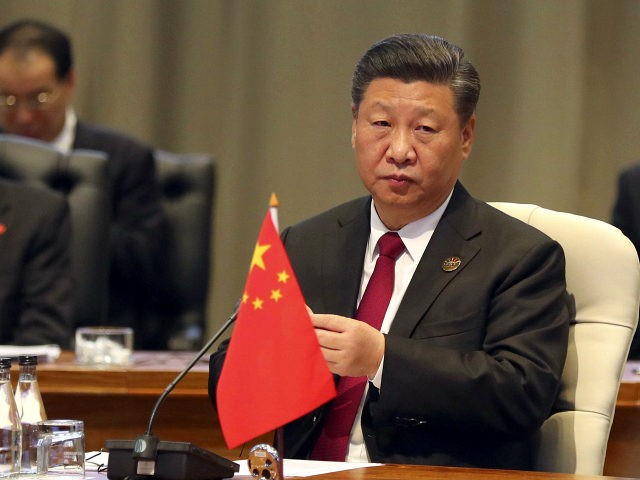

Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping demanded his officials “reject the vulgar, the base and the kitsch” on the internet during a two-day meeting on how to improve state-sponsored propaganda, government media reported Wednesday.

According to Reuters, which cites the original Chinese language report on the meeting at Xinhua, the state news agency, Xi Jinping insisted that the internet must be “clean and righteous,” devoid of content that upsets the Communist Party’s preferences.

The remarks reflect a years-old policy under Xi of censoring political criticism, Western culture, and anything that could lead to Chinese people questioning the wisdom of their leadership.

Xi has struggled to contain online criticism, which has grown on social media since he announced an end to presidential term limits in February. Criticism has risen to unprecedented levels on social media following the revelation that a Chinese biotech corporation deliberately sold faulty vaccines, resulting in hundreds of thousands of children being essentially unvaccinated.

Xi has also used his power in an attempt to contain the growing popularity of Western culture, particularly rap music and hip-hop culture, which China essentially banned from television in January unless it promotes the Communist Party.

“Uphold a clean and righteous internet space,” Xinhua says that Xi told senior propaganda officials at the meeting, occurring on Tuesday and Wednesday. “Reject the vulgar, the base and the kitsch. Put forward more healthy, high quality internet works of culture and art.”

Xinhua’s English-language coverage of the meeting does not mention the internet. Instead, it highlights Xi’s insistence that propaganda leaders promote “unity of thinking and gathering strength” and, especially “traditional Chinese culture.”

“In order to do a better publicity and ideological work under the new circumstances, Xi underlined holding high the banner of Marxism and socialism with Chinese characteristics,” Xinhua reports. “He also stressed adhering to the path of socialist culture with Chinese characteristics and developing a great socialist culture in China.”

“We will improve our ability to engage in international communication so as to tell China’s stories well, make the voice of China heard, and present a true, multi-dimensional, and panoramic view of China to the world,” Xi announced, explicitly noting that “China’s traditional culture serves as the cultural foundation of the Chinese nation.”

The insistence of “traditional” Chinese culture comes as Beijing braces for potential censorship of the second season of The Rap of China, which debuted in July. The first season of the show, an American Idol-style reality competition pitting Chinese rappers against each other, became a breakthrough hit for the streaming service iQiyi last year.

The show became a nightmare for Chinese propagandists, who spent years attempting to promote “patriotic hip-hop” celebrating “Big Daddy Xi” to no avail.

Following the end of the first season, Beijing announced it would ban hip-hop that did not promote communism from television and heavily censored the co-winners of the competition, the rappers PG One and Gai. The rappers found themselves abruptly removed from guest spots on television and forced to apologize for lyrics of which the government did not approve.

The second season of the show appears on the way to become as big a hit as the first one and features international Chinese-language rappers as well as the American hip-hop trio Migos as producers on set to help foster talent, setting up the need for a high-level meeting of Chinese propaganda and censorship leaders to control the show’s popularity.

The idea of limiting thought on the internet is far from a new one to the Xi regime, however. China announced a “national campaign to clean up the online environment” in March.

State media insisted that social media companies and internet corporations “strengthen their self-discipline and supervision against pornographic, obscene and vulgar content.” “Politically sensitive content” was the most pressing to censor, though content that “disturbs the public order” also received notable mention.

Following Xi’s removal of term limits, reports of China’s search engines and social media networks censoring a wide variety of potentially problematic phrases — including “I don’t agree” — began surfacing. Chinese users are also not allowed to use the name “Winnie the Pooh” because it became a code name for Xi, whom critics compared to the portly fictional bear.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.