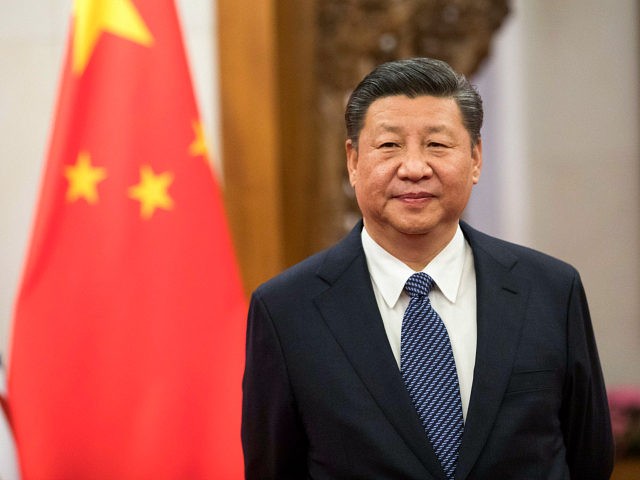

Chinese state media reported Monday that a new round of “discipline” inspections began this weekend, seeking to stamp out graft, inappropriate behavior or any threat to Xi Jinping’s totalitarian rule within the Chinese Communist Party (CPC).

The announcement came hours after the CPC revealed it had taken the first step to repeal the two-term limit on presidents that would have Xi out of office by 2023, helping Xi maintain total control of the party and the country.

The state-run China Daily revealed on Monday that 15 “inspection teams tasked with enforcing Party discipline” have left Beijing to studiously keep tabs on officials in “30 provincial-level regions, ministry-level agencies, and State-owned enterprises.” The list of entities being inspected includes ten cities, 14 provinces, eight ministries, and eight government-controlled corporations, the variety highlighting the full control the CPC has over the nation’s institutions and economy.

The publication claims the investigations will last until “late May” and are necessary because “times have changed and China is facing a new situation.” The official identified as expressing that concern does not elaborate on what exactly has changed that necessitates longer inspections.

Among Xi Jinping’s most significant modifications to the way the Communist Party controls its local chapters has been the creation of inspection groups, beginning with his presidency in 2013. The groups allowed Xi’s Beijing-based Politburo to keep a closer eye on local officials, identify potential threats in Communist officials who did not agree with his reforms, and rapidly purge anyone in the party who may present Xi with a challenge.

The Global Times, another Communist Party newspaper, published a column specifically asserting that the new round of inspections — and upcoming reforms in the soon-to-begin CPC legislative session — will strip CPC officials outside of Beijing from much of their influence. The CPC unveiled proposed changes to the national constitution on Sunday, including the term limit repeal and the creation of a national “supreme supervisory organ” that would “oversee local commissions and answer to the NPC and its standing committee.”

“Under the previous system, the local leadership and the superior anti-corruption agency led the local anti-corruption agency. In the new system, local supervisory commissions will be supervised by their superior commissions and the local people’s congress,” the Global Times explains. “Analysts said the interference and role of local governments in anti-corruption efforts is expected to significantly drop.”

The Times insists this is necessary “to institutionalize the anti-graft drive.”

Xi began his anti-graft drive in 2013, demanding officials begin investigations into accusations of bribery, embezzlement, and other crimes. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection began this campaign in earnest a year later, sending “discipline inspectors” to look through the past of every single member of the Communist Party. By the beginning of 2015, Xi announced that over 2,000 members of the party had been stripped of membership and arrested for a variety of corruption crimes.

Beijing targeted not only civilian CPC members but military leaders. That year, Chinese state media announced the arrests of 14 generals and 39 lawmakers on “graft” charges.

The purge triggered international alarm. Many observers suggested that those targeted for graft happened to be critical of Xi or supporting of alternatives for the presidency. Xi dismissed the accusations, joking that his government was “not House of Cards.”

Most recently, Beijing announced that top general Fang Fenghui had lost his position and face charges of bribery in a military court. That announcement followed the removal of Wang Qishan from the head of China’s corruption agency at October’s Communist Party Congress after he faced accusations of bribery and corruption himself.

As China’s lawmaking body, the National People’s Congress (NPC), is controlled by the CPC, there is little expectation of any resistance to the proposed changes, either to the corruption agency or to Xi’s term limits.

The People’s Daily, yet another Chinese state newspaper, took to defending the latter on Monday, as well. Noting that “president” is the weakest title Xi has — he is also commander-in-chief and head of the CPC — the publication claimed, “it has been proved over history that a leadership structure in which the top leader of China simultaneously serves as the President, the head of the Party, and the commander-in-chief of the military is an advantageous and adoptable strategy.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.