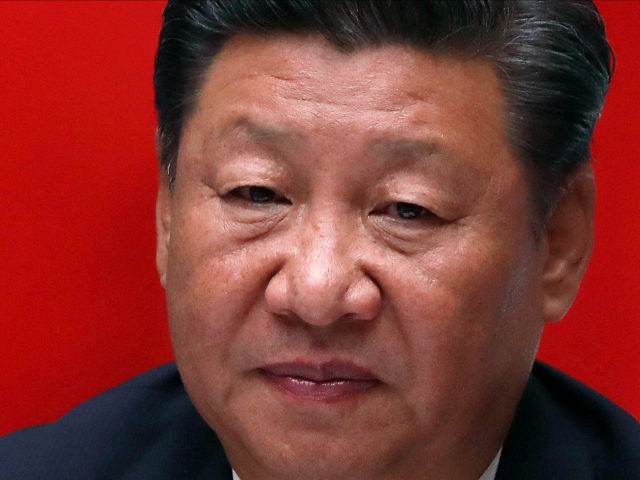

In an interesting footnote to a story from last week, Kirsty Needham of the Sydney Morning Herald noticed that China’s state-run media edited a little detail from the international version of its massive hagiography of President Xi Jinping:

Among his achievements, in the Chinese language version, was that he had turned the South China Sea Arbitration at The Hague – which found against China – into “waste paper.”

It was an achievement that state news agency Xinhua’s lengthy hymn, entitled “Xi and His Era,” did not include in the English version for foreign consumption.

The arbitration tribunal at the Hague comprehensively rejected China’s claim to economic rights across a large, resource-rich area of the South China Sea in a landmark July 2016 ruling. China rejected the ruling as “illegal and invalid” and blasted the Philippines for requesting arbitration from the international tribunal.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was significantly softer in its approach toward China this year than in previous meetings since the South China Sea disputes began, giving Beijing reason to think dismissing the Hague ruling and wearing down the resistance of other regional powers was the right play. The Philippines, in particular, set aside its strongest South China Sea claims after China offered a large financial aid package last year.

Needham wonders if Australia might have reason to worry about a militaristic ruler – she notes he keeps a “photo of himself in military uniform on his desk” – whose agenda includes massive increases in naval and air power, claiming vast regions of the ocean as Chinese territory, exporting “neo-authoritarian” ideology to the developing world, and treating international court rulings like “waste paper.”

It is also curious that Western politicians and analysts who fret constantly about the resurgence of “nationalism” in the United States and Europe have little to say about Chinese nationalism, which is far more outspoken and blatantly aggressive in Xi’s China than under any major political leader in the free world.

Robert Daly of the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute on China and the United States is quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald piece suggesting that China will be “preoccupied with domestic challenges of rebalancing its economic development” over the next five years and therefore is more interested in globalist trade than global domination. He also thinks China will be unable to project “soft power” effectively because its authoritarianism “repulses foreign audiences.”

Those both seem like risk predictions. China may have a lot on its plate domestically, but Xi’s brand of Chinese nationalism virtually demands projecting power abroad, not least by trashing international court rulings and seizing whatever islands catch Beijing’s eye. Freed of liberal democratic concerns about social welfare, China has a lot of money to throw around on expansionist enterprises, and while Xi adroitly uses the language of globalism to woo international audiences, his policies are “China First” to the bone.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.