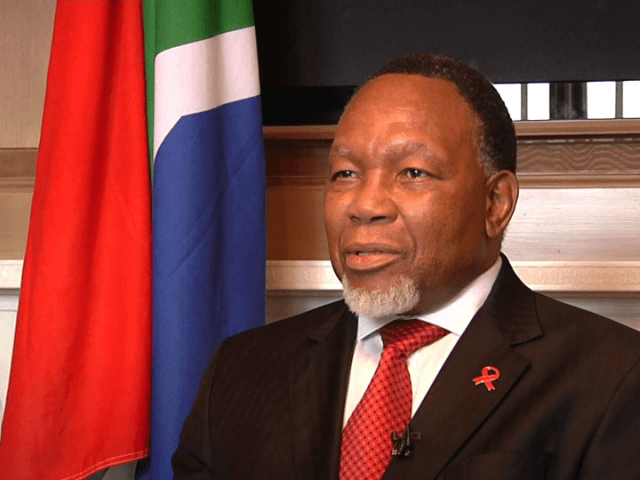

South Africa’s former president Kgalema Motlanthe recently stated that his African National Congress (ANC) party has become so corrupt it should lose the 2019 election for its own good.

A few weeks later, with the ANC coming apart at the seams, political analysts believe incumbent President Jacob Zuma may postpone December’s party elections in a bid to retain power for his faction.

In an interview with the BBC, Motlanthe predicted the ANC’s seeming lock on the South African electorate since the end of apartheid was coming to an end because the party is now associated with “corruption and failure.”

“It would be good for the ANC itself and let me tell you why—because those elements who are in it for the largesse will quit it, will desert it and only then would the possibility arise for salvaging whatever is left of it,” Motlanthe stated.

He added that it was necessary for the ANC to “hit rock bottom” before it can be reformed. “It has to lose elections for the penny to drop,” he anticipated.

Rock bottom has not been reached yet, but it might be dimly visible in the shadowy depths of the political well Nelson Mandela’s party has been plummeting down. Jacob Zuma survived eight no-confidence votes to retain his position, despite an impressive list of charges rattled off by the BBC, ranging from the abuse of public funds for private gain to political profiteering and rape.

In a subsequent interview, Motlanthe zeroed in on Zuma as the major obstacle to reforming the party. “Each one of his mistakes and indiscretions, the ANC takes it upon itself to defend as though he is the ANC,” the former president explained. He hastened to add that he himself would not run for office, so he was not making a self-serving political argument.

Motlanthe seemingly diluted his message, perhaps in response to criticism from party leaders, by saying in a late September radio interview that “I would vote for the ANC because I believe in the ANC.” He framed his earlier comments as a prediction that voters would abandon the ANC unless it offered fresh leadership, rather than encouraging people to vote against ANC candidates to force the party to change.

When a caller to the radio show asked why Motlanthe did not speak up long ago, he said he has been critical of the party at private meetings, but until now he felt it would be inappropriate to speak in public.

“You know‚ as a former president‚ conventions also dictate that I must not be seen to be too critical of the incumbent. The fact that we are at the point where we are speaking shows we are in a deep crisis,” he said.

The prospects for Zuma’s faction of the ANC took a solid hit in September when the High Court of South Africa overturned the elections of several Zuma allies from his home province of KwaZulu-Natal. This could severely compromise the Zuma faction’s influence in the party conference, even if the invalidated officials manage to hang on to their seats until them. In a party already torn by allegations of corruption, refusing to accept the judgment of the High Court that your election was unlawful is not a good look.

Zuma himself, at age 75, is not running again. He is attempting to install his chosen successor, Nkosanzana Diamini-Zuma, a proponent of “radical economic transformation” to address South Africa’s flagging economy, high unemployment, and income inequality allegedly dating back to the apartheid era. In practice, that means “expropriation of land without compensation, nationalization of the Reserve Bank and radical restructuring/redistribution of ownership, structures, and institutions,” as summarized by Max Du Preez at News24.

Whatever else South Africans might think of such an agenda, they are likely to be less enthusiastic about entrusting a corrupt party with radical economic transformation. “Even if she did comprehend the sheer madness of nationalization, land grabs and radical redistribution rather than strong economic growth, she would find it impossible to go against the grain of those to whom she is now beholden,” Du Preez observes.

Diamini-Zuma is locked in a four-way leadership battle with other candidates who lack her corruption baggage, especially ties to the wealthy Gupta family of India, the dark angels of South African politics who are widely seen as controlling Zuma for their own profit.

Du Preez doubts voters will go along with any sort of dramatic economic transformation unless a very long list of Gupta-linked officials, and others who knew of their corruption but were too weak to stop them, is purged from the government and state-owned business enterprises. “If these people remained in their positions, the structures and culture of patronage, rent-seeking, corruption and state capture would continue to wreck South Africa and further cripple the economy,” he argues.

Unfortunately, as he concedes, actually purging all of these people is virtually impossible—he warns it might even provoke violence in the streets—so the ANC will be tempted to serve up “cheap populism” instead of making needed reforms. That strategy may not be enough to save Diamini-Zuma, who is fading fast according to analysts quoted by online news source the South African.

Zuma will, therefore, be sorely tempted to postpone the December party conference, which frankly might need to be called off because it could disintegrate into a physical melee, not to mention various forms of ballot skulduggery. On Sunday morning, the Eastern Cape provincial congress of the ANC ended with members of opposing factions brawling with chairs, bottles, and clubs after accusations of registration irregularity were made. The police were obliged to break up the fight by tossing stun grenades into the room.

Which brings us back around to Kgalema Motlanthe’s original point: It might be impossible to reform the ANC until it loses its power, or at least believes it faces an existential political crisis.

How does one reform a party that cannot hold meetings for fear of violence, and cannot be purged of corrupt officials without sparking riots in the streets—and yet appears to have no serious competition for national leadership, the major opposition Democratic Alliance party having been crushed in a bid to call early elections last month? Bitter factional warfare does not seem like a promising path to constructive reform.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.