The perilous condition of free speech around the world is highlighted by a new report from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, which found blasphemy laws have become “astoundingly widespread” across the world. Some of them specify shockingly severe penalties as well, including torture and death.

The title of the report asks and answers a crucial question: “Respecting Rights? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws.” The Commission strongly rejects arguments that blasphemy laws are needed to protect religious freedom. Instead, it finds them a consistent violation of basic human rights.

USCIRF chairman Daniel Mark said:

Religious freedom includes the right to express a full range of thoughts and beliefs, including those that others might find blasphemous. Advocates for blasphemy laws may argue that they are needed in order to protect religious freedom, but these laws do no such thing. Blasphemy laws are wrong in principle, and they often invite abuse and lead to assaults, murders, and mob attacks. Wherever they exist, they should be repealed.

The report buttressed Mark’s statement by finding that most blasphemy laws “failed to protect freedom of expression, were vaguely worded, and carried unduly harsh penalties for violators.” Every single blasphemy law was found to deviate from “at least one internationally recognized human rights principle,” with freedom of expression and freedom of religion obviously the most commonly trampled rights.

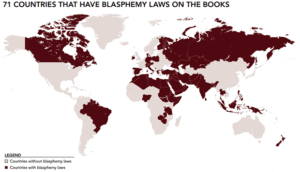

The raw numbers are chilling: 71 of the 195 nations currently recognized in the world have blasphemy laws. 86 percent of those laws prescribe imprisonment or worse for offenders.

The distribution of blasphemy laws around the world might come as a surprise. Only 25.4 percent of them are found in the Middle East and North Africa. A roughly equal percentage of the world’s blasphemy laws can be found in the Asia-Pacific Region, and Europe lags only slightly behind, with 22.5 percent. 15.5 percent come from sub-Saharan Africa, while 11.2 percent can be found in the Americas.

USCIRF notes that enforcement of blasphemy laws tends to be more relaxed in some areas, which gives the Commission optimism that reform is possible. Then again, one of the countries cited as having relatively relaxed anti-blasphemy enforcement is Canada. The country that scored best on the USCIRF’s index of freedom for nations with blasphemy laws is Ireland. The report takes pains to note that blasphemy laws are by no means relegated to the far corners of the Third World.

The portion of the world currently covered by some sort of blasphemy law, as depicted in a map provided by the USCIRF, is even more sobering than the raw numbers:

Some of these laws, like Canada’s, are general proscriptions against offending all religions, at least in theory. The countries with the worst oppression scores are all Islamic: Iran, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and Qatar. Iran and Pakistan both have the death penalty for blasphemy.

On the other hand, Italy comes in at Number 7 on the list of most repressive blasphemy laws, with stiff fines and prison sentences for insulting the Catholic Church. Malta was Number 10 with stringent laws against blaspheming the Roman Catholic Apostolic state religion, but it repealed its blasphemy law after the report was compiled. Denmark also repealed a fairly severe blasphemy law in June 2017.

In many other cases, USCIRF cites the vague nature of blasphemy laws as a strike against them, since enforcement can be mercurial according to the whims of officials or the demands of angry mobs. The analytical section of the report notes that having an official state religion is one of the most reliable indicators that blasphemy laws will become oppressive and discriminatory, but not every country with such laws specifies a state religion.

A few interesting aberrations in the scoring methodology are noted in the report. For example, Grenada specifically criminalizes the sale or publication of blasphemous or obscene books but intrudes much less into free speech or individual privacy than most other nations with blasphemy laws. Saudi Arabia scores relatively low on the repression index, despite having notoriously strict punishments for defaming Islam, because the Saudis do not have a written penal code – they are entirely governed by Islamic sharia law.

The report also offers an extensive comparison of Egypt and Italy, which have comparable numeric scores for their blasphemy laws under the USCIRF’s methodology but are vastly different in the way those laws are implemented in practice. Italy, for example, handed down its most recent known blasphemy indictments in 2009, but they are much more common in Egypt, even after the Muslim Brotherhood was overthrown by current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in 2013. In fact, the frequency of blasphemy prosecutions in Egypt has been steadily increasing since the ouster of longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak in 2011, with 21 cases reported between 2015 and 2016.

Also, the report grimly notes that, while Bangladesh has blasphemy laws of only average severity on the books and the national constitution specifically protects freedom of religion for non-Muslims, Islamist vigilantes routinely attack and kill accused blasphemers.

The Economist quotes an interesting comment from Irish politician Mairead McGuinness, who serves as vice president of the European Parliament. McGuinness pointed out that, “when Europeans criticize the abusive blasphemy or apostasy laws in countries such as Indonesia, Pakistan, Sudan, or a host of others, the local authorities frequently accuse us of hypocrisy.” Therefore, she called for a referendum to abolish Ireland’s relatively mild blasphemy law, presumably hoping other European nations would follow suit.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.