At the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) meeting this weekend, Australia and Japan joined the United States in calling for a legally binding “code of conduct” for the South China Sea. More to the point, they want an internationally-recognized legal barrier to China’s conduct in the region.

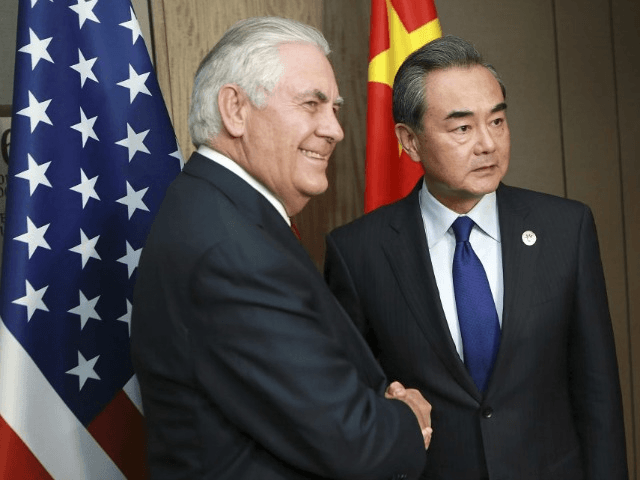

As the Philippine Star observes, the statement from U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop, and Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kano was “considerably stronger than a joint statement of concern issued by their counterparts in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.”

A statement from the three nations, whose meetings are known as the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue (TSD), stressed the importance of “upholding the rules-based order” and called upon all states to “respect freedom of navigation and overflight and other internationally lawful uses of the seas.” The TSD swiftly clarified that they were talking about the South China Sea and looking at China when they spoke:

The ministers expressed serious concerns over maritime disputes in the South China Sea (SCS). The ministers voiced their strong opposition to coercive unilateral actions that could alter the status quo and increase tensions.

In this regard, the ministers urged SCS claimants to refrain from land reclamation, construction of outposts, militarization of disputed features, and undertaking unilateral actions that cause permanent physical change to the marine environment in areas pending delimitation.

The ministers called on all claimants to make and clarify their maritime claims in accordance with the international law of the sea as reflected in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and to resolve disputes peacefully in accordance with international law.

The ministers called on China and the Philippines to abide by the Arbitral Tribunal’s 2016 Award in the Philippines-China arbitration, as it is final and legally binding on both parties.

The ministers noted the significance of the UNCLOS dispute settlement regime and the Tribunal’s decision in discussions among parties in their efforts to peacefully resolve their maritime disputes in the SCS.

The ministers urged ASEAN member states and China to fully and effectively implement the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC).

This was followed by the call for a “Code of Conduct for the South China Sea,” which was given its own acronym, “COC.” The Code of Conduct envisioned by the U.S., Australia, and Japan would be “legally binding, meaningful, effective, and consistent with international law.”

The East China Sea was also mentioned in the statement, with similar warnings against “any coercive or unilateral actions that could alter the status quo and increase tensions.”

As mentioned above, ASEAN’s statement on the South China Sea was much softer, in part because the ASEAN nations ended up in a diplomatic impasse over how strong the wording should be. China has, it would seem, bullied most of the Association nations out of even mentioning the military facilities Beijing has been installing on disputed islands and reefs.

According to Japan Times, the big clash behind the scenes at ASEAN was between Vietnam and Cambodia. Vietnam, which has vociferously argued with China over certain disputed islands, wanted very tough language against Chinese land reclamation projects inserted in the ASEAN statement, but China’s firm ally Cambodia resisted those demands. One diplomat said Cambodia has effectively become China’s voice at ASEAN on South China Sea affairs.

The statement ASEAN ended up releasing merely expressed concern over “land reclamations and activities” in the area that have “eroded trust and confidence, increased tensions and may undermine peace, security and stability in the region.”

As for the South China Sea Code of Conduct, Secretary of State Tillerson and his Australian and Japanese counterparts needled China for failing to produce such a code in a timely fashion, because China has technically been working with ASEAN on developing a framework for over 15 years. Tiny reefs have blossomed into Chinese military airfields while China works on writing a code of conduct that would prevent Pacific nations from turning tiny reefs into military airfields.

In its current form, the framework primarily offers guidance for avoiding tense incidents between the aircraft and naval vessels of various nations in the South China Sea—a far more limited code than what the U.S., Australia, and Japan have in mind.

In fact, as one analyst pointed out to Japan Times, the current “framework” for the Code of Conduct is little more than a list of topics. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi offered some encouragement on Sunday that negotiations on a more substantial code could begin in November.

Another bit of South China Sea drama at the ASEAN conference involved the host country of the Philippines, which wanted to release a statement calling for “non-claimant nations” to stay out of territorial disputes. “Non-claimant nations” means those without direct claims on South China Sea territory, which primarily means the United States. By an interesting coincidence, ruling out interference from non-claimant nations just happens to be one of China’s preconditions for negotiating the Code of Conduct.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.