CARACAS, Venezuela – Driving through the streets of Caracas, it is impossible not to notice the ubiquitous government propaganda on the sides of buildings and scores of armed police.

Even harder to avoid, however, is the garbage.

On almost every street corner, stacks of waste can be seen piled up, some of it in black bags, but other items in limbo such as water bottles, diapers and occasionally food waste.

Around almost every pile of garbage, a crowd had formed, rifling through it for scraps to eat. From schoolchildren to the elderly, even to those in work uniform, many Venezuelans are resorting to scavaging just to survive. A recent report found that over 15 percent of people scavenge as a means of survival.

Those who eat what they find have developed the skill of finding edible bits of food where they can. In an interview with Colombia’s El Tiempo, for example, one woman noted that some neighborhoods are known for having the “good” garbage – the kind with food in it that can be recooked and consumed, as opposed to non-food waste.

A woman and her teenage daughter, who can be seen wearing a school backpack, search for food in garbage bags.

Huge amounts of waste are routinely dumped on roadsides. A pro-government by-stander scolds me for taking the photo. Anything showing Venezuela’s extreme poverty is considered a crime against the state.

Middle-aged men ruffle through bin bags. Drainage systems are also inundated with waste, increasing the risk of flooding.

A roadside is covered in waste within a busy market.

Stray dogs can be seen scavenging through garbage. Some Venezuelans have now resorted to eating dogs just to survive.

Anti-government protesters regularly place bin bags in the middle of the road to prevent vehicles from accessing marches.

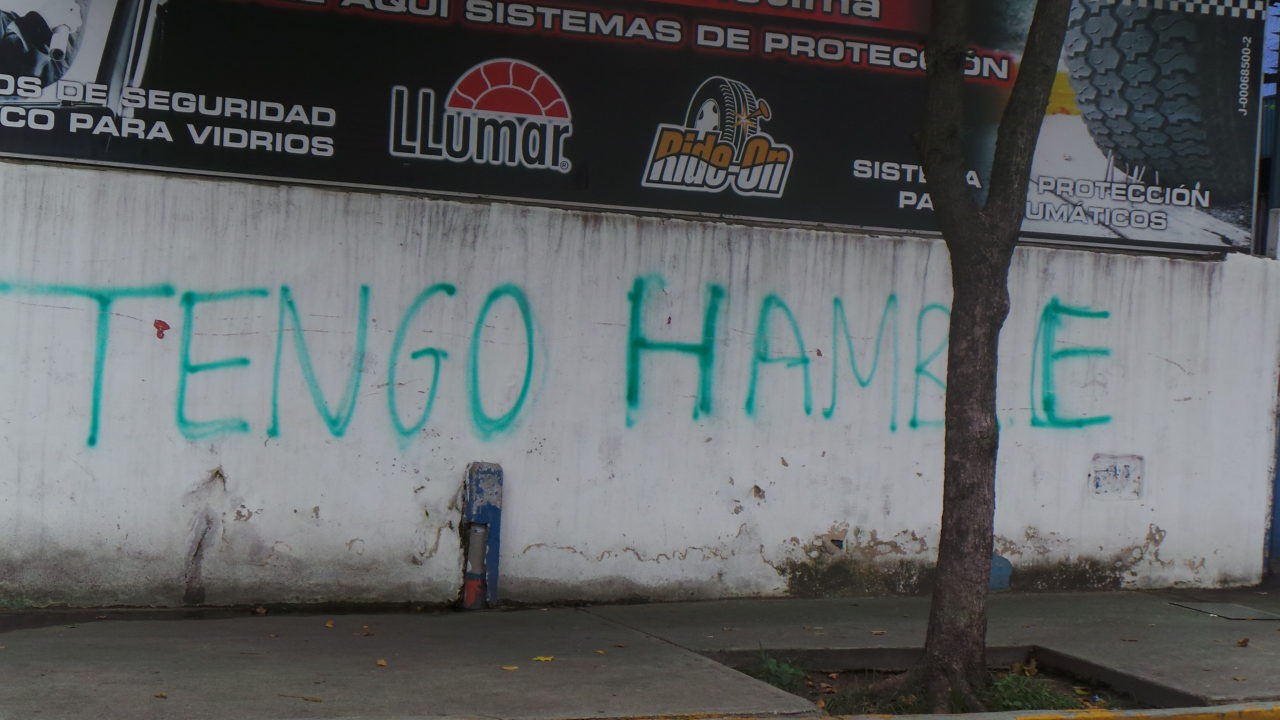

“I AM HUNGRY”

The country’s problems with managing landfill are well documented. Venezuela’s waste management system has been largely non-existent for much of the Chavista era. In 2007, a Lonely Planet travel guide to Venezuela warned foreign visitors that waste management was “far and away the most obvious environmental problem in Venezuela,” with “no recycling policy and dumping of garbage in cities, along roads and natural areas is common practice.” In some neighborhoods, garbage trucks simply fail to come around for over a week, resulting in large heaps of garbage on the streets.

“The fundamental problem has been planning, which has stagnated the solid wage management systems [in Venezuela] for 20 years, because in the past two decades, the exact same thing has been done despite the evolution of technology as well as recycling measures that have evolved,” Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV) professor Juan Carlos Sánchez explained at a 2016 presentation.

There is little evidence that Maduro has implemented reforms to change the waste management system, despite his claims of environmentalism. Venezuela remains a signatory of the Paris Climate Agreement and under former president, Hugo Chávez’s leadership launched a number of environmental initiatives such as “Mission Tree” that promoted conservation and sustainable development. However, such initiatives appear to have been sidelined under the Maduro regime, and it is unclear how, if at all, Venezuela is working to meet the commitments in the Paris agreement.

This did not stop Maduro from criticizing President Donald Trump’s withdrawal announcement from the Paris Agreement, accusing Trump of “turning his back on the world.”

Maduro has blamed corruption, private enterprise, and the United States generally for the country’s current state of emergency.

In addition to the unsightly nature of the problem and environmental dangers, the waste is also likely to present a serious health hazard, particular given the South American nation’s status as one of the countries most affected by the Zika virus. Stagnant pools of water, easily created by standing waste after rainfall, breed mosquitos that spread the disease. The government has refused to disclose numbers of Zika victims or other key details to keeping the public safe, and the Colombian Health Minister last year accusing Venezuelan health officials of “an epidemiological silence” on the problem.

Even if Venezuelan government officials sought to solve the problem now, they would have to improvise on what to use to solve it. Venezuela is lacking hygienic products to tackle the mess, with chronic shortages of products such as detergent, disinfectants, and general cleaning materials.

You can follow Ben Kew on Facebook, on Twitter at @ben_kew, or email him at bkew@breitbart.com

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.