This morning’s key headlines from GenerationalDynamics.com

- The First Thanksgiving — The Pilgrims meet the Wampanoag Indians

- The fur trade with Britain and Europe

- King Philip’s war

- Aftermath of King Philip’s War

- The Great Awakening of the 1730-40s

- The Revolutionary War — 1772-1782

- Aftermath of the Revolutionary War

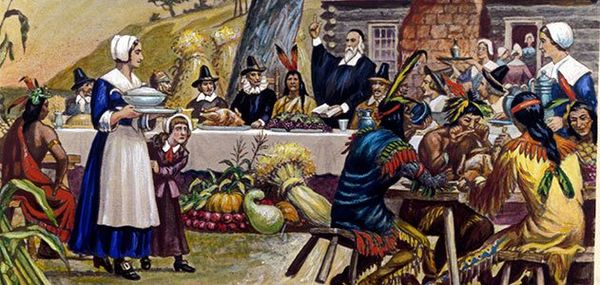

The First Thanksgiving — The Pilgrims meet the Wampanoag Indians

The First Thanksgiving

In the year 1600, throughout what is now the United States, it’s estimated that there were some 2 million Indians within 600 tribes speaking 500 languages. What happened, starting at that time, was a “clash of civilizations” between European culture of the colonists and the indigenous culture of the Indians. These cultures were so different that haven’t yet merged even today, inasmuch as many Indian tribes still live separately on reservations. It’s ironic that the American “melting pot” has merged so many cultures, but has not yet entirely merged the preexisting Native American cultures.

As with all tribes and ethnic groups in all places around the world, there were undoubtedly many brutal wars among the 600 tribes of the time. If there had never been any colonists, then the Indian tribes would have fought wars of extermination with each other, and probably today there would be one major tribe that was running the entire country, with other smaller tribes marginalized and discriminated against, perhaps even in reservations.

In this story, we’re going to focus on just one Indian tribes: The Wampanoag tribe that occupied what is now southeastern Massachusetts (where Plymouth Rock is).

There is some historical evidence that there was a major war among the Wampanoag tribe and the Narragansett tribe that occupied what is now Rhode Island, and the Mohawk tribe (part of the Iroquois) of upstate New York. This war occurred in the years preceding the colonists’ arrival at Plymouth Rock, probably in the 1590s. The Wampanoag and the Narragansett tribes were particularly devastated and weakened by that conflict.

So, when the pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock in 1620, in the midst of the Wampanoag tribe during a generational Awakening era (like America in the 1960-70s), the Indians were still war-weary, and were quite friendly to the pilgrims. There were even some Indians who, astonishingly, spoke English because they had been kidnapped by an English sea captain and sold into slavery, but escaped in London. One of them, Squanto, helped the pilgrims learn to hunt, fish and survive.

The pilgrims, led by Governor William Bradford, and the Wampanoags, led by chief Massasoit, developed a warm relationship. In November 1621, after the successful corn harvest, they celebrated with a feast now remembered as “America’s First Thanksgiving.”

Thanksgiving has been celebrated annually since then, and in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln made it a national holiday.

The fur trade with Britain and Europe

The Pilgrims were committed to have nothing to do with the English King and parliament. They had signed the Mayflower Compact, where they agreed that they would be governed by the will of the majority. They could provide for themselves, and they were friendly with the Indians.

This friendliness extended to trade. Before long, there was a mutually beneficial financial arrangement between the Indians and the colonists. The colonists acted as intermediaries through whom the Indians developed a thriving business selling furs and pelts to the English and European markets, and they used the considerable money they earned to purchase imported manufactured goods.

King Philip’s war

By the 1660s, the Wampanoag tribal society had entered a generational Crisis era, and relationships between the colonists and the Indians began to deteriorate.

William Bradford had died in 1657, and Massasoit died in 1661. The personal ties between these leaders had vanished, and younger generations of colonists and Indians rose to power with personal friendships replaced by mutual xenophobia.

A generational Crisis era is usually accompanied by a major financial crisis — that’s certainly true in the world today. Things really began to turn sour in the 1660s because styles and fashions changed in England and in Europe. Suddenly, furs and pelts went out of style, and the major source of revenue for the Indians almost disappeared. This resulted in a financial crisis for the Indians, and for the colonists as well, since they were the intermediaries in sales to the Indians. Then and now, a financial crisis only feeds into and increases xenophobia, racism and nationalism, as different societies, races and nations blame each other for the financial crisis.

Massasoit was replaced as Wampanoag chief by his youngest son, Metacomet, who was nicknamed “King Philip” by the colonists. Relations between King Philip and the colonists worsened, and things came to a head in 1671, when King Philip himself was tried for a series of Indian hostilities, and required by the court to surrender all of his arms. He complied by surrendering only a portion of them.

Relations continued to deteriorate, and King Philip’s War began in 1675, with Philip’s attack on the colonists on Cape Cod. The war was extremely savage and engulfed the Indians and the colonists from Rhode Island to Maine. There were atrocities on both sides, and the war ended with King Philip’s head displayed on stick. His wife and child were sold into slavery.

This was the most devastating war in American history on a percentage basis, with 800 of the 52,000 colonists killed. (It was devastating for the Indians as well.)

Aftermath of King Philip’s War

After the devastating, people began to ask: Why weren’t English soldiers here to defend us?

That brings us back to the Mayflower Compact, signed in 1620, which guaranteed that local government would be independent of the English Crown. The colonists had thought they would build their new community without outside interference, with their own rules and their own self-government.

After the devastation of King Philip’s war, they felt forced to acquiesce completely to English rule. All home rule was dissolved and Governors would be appointed from London. British troops would protect the colonists from the Indians and the French, and colonists would pay taxes to the Crown in return.

The Great Awakening of the 1730-40s

Anyone who was around during America’s Awakening era of the 1960s and 1970s will recall the “televangelists” – people like Herbert W. Armstrong, Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, Jerry Falwell, Jimmy Swaggart, Pat Robertson, Oral Roberts, and dozens of others.

A similar thing happened in the 1730s-40s. Historians have named this period “The Great Awakening in American history,” and in fact the phrase “generational Awakening era” was derived from this historical name.

Just as America’s youthful Boomers were rebelling against their parents in the 1960s, the colonists’ young generations in the 1730s were rebelling against everything English, including the Church of England, known as the Anglican Church in the colonies.

The issue of government by the English Crown was a divisive issue at that time. The older generations had ceded power to London in return for the protection of the English army. The younger generations rebelled against giving all this power to the Crown.

The Anglican Church never did have much success in establishing religious control in the colonies, as congregations of Puritans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Quakers and many other religions sprang up in the colonies from the beginning, and had to compete with one another for followers.

Starting in the 1730s, something brand new came about – something we recognize today in the form of “televangelists.” Various preachers went from city to city, telling thousands of rapt listeners that they would be punished for their sinfulness, but could be saved by the mercy of an all-powerful God. To take one example, John Wesley, born in 1703, created the Methodist religion, and traveled on horseback throughout the country for years, stopping along the way to preach three or four sermons each day.

The Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s was not just a religious revival; it was also an act of rebellion against the older generation that favored control by the British in return for protection. By rejecting the Anglican Church, the young colonists were symbolically rejecting British control.

The Revolutionary War — 1772-1782

All the contradictions and compromises that were forced upon the colonists following the devastation of King Philip’s War came to a head in the Revolutionary War. In particular, the taxes that England had levied against the colonies to pay for protection from the Indians and the French led to colonist demands for “No taxation without representation!”, the catchphrase for pre-Revolutionary days.

By the 1760s, the British were moving to consolidate their control over America as a British colony. In particular, the Sugar Act and Currency Act of 1764 were imposed in order to prevent the colonies from trading with any foreign country except through England as an intermediary. The Stamp Act of 1765 was enacted to recover at least a fraction of the money England had to spend to maintain its military forces in the colonies.

These moves by England hardly seem unreasonable. The colonies were expensive children, and like a parent expecting his children to pay a little rent, England had a right to expect the colonists to pay for a portion of the cost of protecting them.

But the pressure for revolution had been building for a long time. The Stamp Act was particularly galling. All printed documents, including newspapers, broadsides and even legal documents, had to have a stamp affixed, with the cost of the stamp being paid to England.

An underground terrorist group called the Sons of Liberty was formed. This group used violence to terrorize Stamp Act agents and British traders in numerous towns. However, violence was rare: colonial opposition was designed to be non-violent. The colonies formed a “Stamp Act congress” to call for repeal. English imports were boycotted. The English sought to contain the problem and compromise. As a result, the Stamp Act was repealed by 1766.

However, England was still trying to find a way to collect revenue from the colonies without engendering riots, but they never succeeded. In 1767, England passed the Townshend Acts, imposing further taxes on goods imported to the colonies. Four more years of increasingly virulent protests forced England to repeal the taxes in 1771.

There is no question that England was doing everything it could to compromise and contain the situation. When occasional violence broke out, it was contained. In the most well-known incident, the 1770 Boston Massacre, where British soldiers fired into a crowd and killed five colonists, two of the soldiers were tried and convicted, and tensions were relieved again.

By 1771, all taxes had been repealed except a tax on importation of tea, and even that tax was often evaded. From a purely objective view, the colonists really had few major grievances at this time.

However, a financial crisis occurred in July 1772, when the English banking system suffered a major crash. Many colonial businesses were in debt to the English banks, and were suddenly unable to obtain further credit, forcing them to liquidate their inventories, thus ending their businesses.

In May 1773, The English Parliament passed a new Tea Act, and in December 1773, a group of Boston activists dumped 342 casks of English tea into Boston Harbor.

The Boston Tea Party can hardly be called a major act of violence. Tea was expensive, of course, 342 casks of English tea shouldn’t have been something to cause a war.

Nonetheless, the Boston Tea Party, has become world famous. It was so electrifying at the time that it surprised and shocked both the colonies and England. After that, one provocation after another on both sides finally led to war.

The furious English Parliament passed a series of “Coercive Acts” to dismantle the colonial Massachusetts government, close the port of Boston, and control the hostilities. This was tantamount to a declaration of war. With positions on both sides becoming increasingly hardened, war was not far off.

Hostilities actually began in April 1775, when the colonial minutemen attacked the British forces following the midnight ride of Paul Revere. The separation became official on July 4, 1776, when the Continental Congress endorsed the Declaration of Independence.

The war continued until November 30, 1782, when American and British representatives signed a peace agreement recognizing American independence.

Aftermath of the Revolutionary War

The end of the Revolutionary War didn’t mean the end of the American crisis. There were still grave doubts as to whether the Union could survive. The colonies had formed a very weak Confederation, which left each former colony largely autonomous, adopting its own currencies, taxes, laws and rules. The economy suffered a major recession in 1786, resulting in severe acts of terrorism by bankrupt farmers and businessmen – acts that couldn’t be controlled since the terrorists could not be pursued across state lines because there was no federal army. The crisis did not end until 1790, after the Constitution was ratified and George Washington became president.

A generational crisis war is so horrific that the survivors, both the winners and losers, are willing to make compromises to make sure that nothing like it happens again. The survivors of King Philip’s War had agreed to a compromise that allowed Britain to rule the colonies and collect taxes in return for the protection of the British army. That compromise became the issue that led to the next crisis war, the Revolutionary War.

The Revolutionary War was also resolved with a major compromise – one that permitted slavery to exist in the South, though it was made illegal in the Northern states. The slavery compromise was necessary to create the nation in the first place. But it was also the seed that grew into the issue that almost destroyed the nation in the next generational crisis war – the American Civil War.

Note: This material was adapted from Chapter 2 of my book, Generational Dynamics – Forecasting America’s Destiny, which is available as a free PDF from my download page, http://generationaldynamics.com/download

KEYS: Generational Dynamics, Pilgrims, Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Rock, First Thanksgiving, Massasoit, William Bradford, Metacomet, King Philip, King Philip’s War, Mayflower Compact, Church of England, Anglican Church, John Wesley, Methodists, Puritans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Quakers, Great Awakening, Sons of Liberty, Stamp Act, Boston Massacre, Tea Act, Boston Tea Party, Revolutionary War, Coercive Acts, Paul Revere, Declaration of Independence, American Civil War

Permanent web link to this article

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.