The American Revolution matters today more than ever.

Terrorism, globalization, technology, and political correctness threaten America’s unique national identity. Since 9/11, liberties have been poached and the Constitution scorned. In these turbulent times, many Americans are thirsting to discover the roots of the founding and reclaim the essence of the idea that became the United States of America.

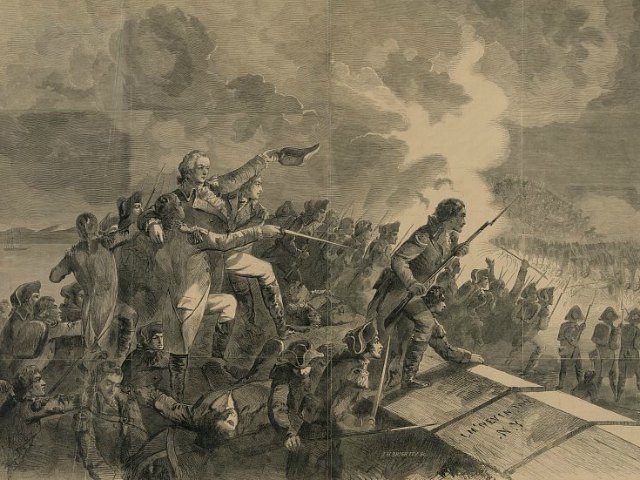

The forgotten revolutionary raid at Stony Point exemplifies American courage, innovation, and grit. It typifies American DNA and who we are as Americans.

On July 15, 1779, the night was cold, and the wind lashed at the faces of the American light infantry moving through the darkness. One by one, the Continentals stepped off solid ground and plunged into waist-deep, thick, green muck. Because the slightest noise could alert the British to their presence, resulting almost certainly in instant death, the men maintained silence. They were part of a twenty-man commando-like team called a “forlorn hope”—in today’s lexicon, a suicide squad. They served as the tip of the spearhead assaulting one of the most heavily defended British fortresses in North America.

With heavy axes and muskets, the men had to cut a hole through the abatis—pointed, blade-like, wooden stakes that were waiting for them, poised to tear into their flesh. Until the abatis was removed, the rest of the assault force would be unable to enter the fort. The forlorn hope would slowly hack their way through the timbers while under constant fire from the enemy. If they made it through alive, they would have to begin the process again and chop through yet another row of thick abatis.

The story of this battle is recounted in a new bestselling book, Washington’s Immortals, which chronicles the efforts of the elite troops of Maryland, some of whom played a key role at Stony Point. This unique book is the first Band of Brothers treatment of the American Revolution, detailing the most important elements of nearly every significant battle of The War of Independence.

The fortifications at Stony Point, New York, sat on a ninety-acre piece of land that juts out into the west side of the Hudson River. With steep, 150-foot cliff faces on three sides and a marsh on the other side, the site had excellent natural defenses. On May 30, 1779, the British had seized control of both Stony Point and Verplanck’s Point, another fort on the opposite side of the river, directly across from Stony Point. The two forts cemented British control of the Hudson and threatened the American defenses at West Point just 13 miles away.

At this point, the War of Independence had dragged on for more than three years, and the Americans had survived a brutal winter at Valley Forge. After carefully gathering actionable intelligence on the British outpost, Washington ordered a raid to assault Stony Point and remove the threat which the British fortification posed to American defenses. Rather than deploy his entire army, which could have played into a British counterattack, Washington unleashed more than 1,000 men from his light infantry, a corps “composed of the best, most hardy and active marksman.” The volunteer force was unencumbered by baggage and heavy artillery and earned renown for their daring, alertness and efficiency.

In order to accomplish this mission, the American officers sought volunteers for the forlorn hope and a hundred-man advance guard. The advance guard would be the first troops to enter the fort after the forlorn hope chopped through the walls, and they would bear the brunt of the enemy’s defensive efforts. Many Marylanders answered the call, including free African American George Dias. Although history books don’t often mention their contributions, as much as 10 percent of the Maryland troops in the American Revolution were African Americans.

Before the group had set out around noon, General “Mad Anthony” Wayne had ordered, “Should there be any soldier so lost to every feeling of honor, as to attempt to retreat one single foot or skulk in the face of danger, the officer next to him is immediately to put him to death.” The same fate would befall any man who spoke or discharged his musket. The officers carried spontoons—long, menacing, razor-sharp iron pikes on the end of wooden poles—which would be used without hesitation to fulfill General Wayne’s order should the need arise. And the need did arise—at least one man who tried to flee was run through by an officer.

In complete silence, the Patriot forces marched more than 13 miles across mountainous terrain that was so rugged that they frequently were forced to move in single file. By the time they reached the fortifications at Stony Point, it was the middle of the night. Alert British sentries caught sight of the approaching Americans and opened fire. The forlorn hope tore into the abatis while the enemy spewed musket fire and grape shot. They managed to cut a small opening in the first abatis and pushed their way through to the second, many of them catching clothing and flesh on the sharpened sticks as they passed.

Yelling, “The fort’s our own!” the men soon breached the fort’s upper defenses. Vincent Vass, a member of the forlorn hope, said he heard the “blares of Cannon and Small arms” as he charged through. Fighting his way to Stony Point’s upper works, he had “received two wounds, a musket ball Scaled the bone of my hip, a buck shot entered my thigh.” The friend who had volunteered for the forlorn hope alongside him was also injured.

As the Americans enveloped them, the British desperately attempted to re-form and repel the oncoming enemy. Vass said he heard the British cry out in the melee: “Quarters, quarters brave Americans! Mercy! Mercy! Dear Americans, quarter, quarter!”

Within thirty-three minutes, it was over. The two sides lost nearly an equal number of killed and wounded—around one hundred men. The American light infantry captured 472 British and Loyalists. At 2:00 a.m. Wayne wrote to Washington: “Dear General,—The fort and garrison, with Colonel Johnson, are ours. Our officers and men behaved like men who are determined to be free.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of ten books Washington’s Immortals is his newest bestselling book. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah, and he was nearly killed by Chechen terrorists during a firefight. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickKODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.