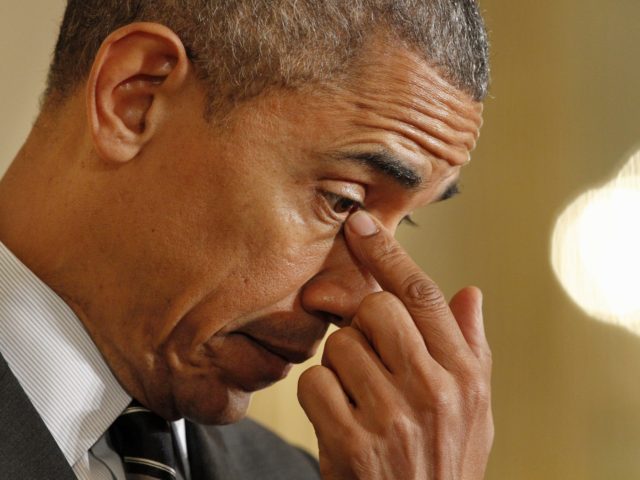

President Obama began his Wednesday speech announcing his intention to abandon all efforts at withdrawing U.S. troops from Afghanistan by touting a list of successes.

Since 2001, he said, the American-led coalition “pushed al Qaida out of its camps, helped the Afghan people topple the Taliban and helped them establish a democratic government.” With 9/11 mastermind Osama bin Laden dead and al Qaida’s capacities greatly diminished, Obama added, the war in Afghanistan “came to a responsible end” nearly two years ago.

Except, of course, for how it didn’t. Remember, this is still the speech about delaying U.S. exit from Afghanistan for the foreseeable future. Obama’s victory narrative might be appealing, but it is stretched beyond all recognition by the meat of his announcement—namely, that there is no known end in sight for the lengthiest military entanglement in our history.

In making his case, Obama conveniently leaves an open door to endless imbroglio, fails to convince that continued intervention is in American interests, and projects an idealistic goal of Afghan transformation that will never let this misadventure end.

Obama’s list itself suggests just how knotty an entanglement Afghanistan has become. From an initially limited vision of holding responsible those who had aided and abetted an attack on the United States, the war in Afghanistan has long since spiraled into a messy nation-building project in which, as currently conceived, America’s role can continue ad infinitum.

Even as he conceded that “Afghan forces remain in control of all the major population centers, provincial capitals, major transit routes and most district centers,” Obama maintained that because “Afghan security forces are still not as strong as they need to be” and “the Taliban remains a threat,” the United States’ wildly expensive and poorly defined occupation must continue.

This pliable language leaves Obama—not to mention the next president—utterly without a rubric to bring our troops home. The Afghan security forces will never be as strong as they possibly could be given more American time and billions, and the Taliban and its copycats and successors will always seek to be a threat. Another ten years and 10,000 troops won’t change that.

A realist assessment of Afghanistan’s situation is not silly enough to posit perfection as the requirement for this chapter in U.S. foreign policy to come to a close. Whatever he may say, in nixing all chance of near-term exit, Obama here wants nothing of realism.

Worse yet, what’s notably lacking from Obama’s argument is any convincing indication that this ongoing military commitment has a clear connection to America’s vital interests. Afghanistan is still dangerous, to be sure, but it is more stable than it used to be—plus thousands of miles away. We are protected by the world’s largest two moats, friendly bordering neighbors, and far and away the most powerful military on the globe.

Absolute security is unachievable, but fiddling with the graveyard of empires for another generation isn’t a step in that direction.

Indeed, Afghanistan doesn’t have to be transformed into Mayberry for our intervention there to be rightfully finished. To claim otherwise at this point in the war is liberal interventionism at its worst: license for what has become a sprawling social project which does little to directly defend U.S. national security.

By suggesting we must stay until this project is perfected, Obama points the United States toward a utopian objective which frees him and future administrations from any accountability to the American people. There will always be a few more tweaks to make, no matter how many years we occupy, and there will almost certainly always be a power-hungry resident of the Oval Office happy to have that war-making leeway.

“When we first sent our forces into Afghanistan 14 years ago,” Obama said toward the end of his remarks, “few Americans imagined we’d be there—in any capacity—this long.” That’s true, but after a speech like this, it unfortunately isn’t hard to imagine we’ll still be there 14 years from now.

Bonnie Kristian is a fellow at Defense Priorities. She is a contributing writer at The Week and a columnist at Rare, and her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, Relevant Magazine and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.