In the wake of the Paris and San Bernardino terrorist attacks, there has been increased pressure on social media companies to take down Islamist material to interfere with their recruiting efforts, but the companies are also worried about allegations of censorship.

In fact, according to a Sunday Reuters article, former employees of Facebook, Google, and Twitter “all worry that if they are public about their true level of cooperation with Western law enforcement agencies, they will face endless demands for similar action from countries around the world.”

They are equally worried about “being perceived by consumers as being tools of the government”… or the tools of non-governmental activists who also pressure them to censor certain material. There is also some pressure to keep militant accounts active because intelligence agencies glean valuable information about terrorists by studying their online activities.

For good measure, social media providers are concerned that if more details of their screening processes are made public, militants will learn how to defeat them.

And all of these considerations must be weighed quickly because everything happens fast on the Internet. The Reuters article mentions that government officials and activist groups sometimes get swift results by simply pointing out that objectionable material violates a social media company’s terms of service – which almost invariably prohibits posting incitements to violence, for example – and letting the company self-censor targeted postings in a matter of hours. One activist with experience at using such techniques described it as “commonplace for federal authorities to directly contact Twitter and ask for assistance, rather than going through formal channels.”

Such was the case with the Facebook page maintained by San Bernardino jihadi Tashfeen Malik, which she created under an alias. It was quickly taken down on Friday for violating Facebook’s terms of service, as it reportedly contained pro-ISIS propaganda.

There is potential for abuse, including what amounts to old-fashioned state-imposed political censorship, with these “workaround” methods. For instance, Reuters notes that social media providers generally use algorithms to flag accounts that might need to be suspended because they do not have the time to conduct a thorough review of every item that attracts a small number of complaints. These algorithms can be exploited by determined activists and government-run operations, as in the case of evidently coordinated campaigns to blow critics of the Russian and Vietnamese governments off Facebook.

Although Reuters does not mention it, the “flag-spamming” campaigns, used by activist mobs in the United States to hound users they disagree with off Twitter, could be viewed as similar abuses. One solution explored by companies like Google is to grant enhanced flagging privileges to trusted users, giving them an enhanced ability to report offensive material and obtain quick action from service providers.

Such “trusted flagger” status is reportedly reserved for non-governmental groups. Of course, the line between government and “activist” can grow quite blurry, especially when individual people are passing through revolving doors between government service and NGO employment. Even in the free-speech bastions of the Western world, it is not hard to find non-government activists groups happy to support an official agenda, and while few tears are shed over vaporized ISIS fan pages or shuttered terrorist Twitter accounts, eventually people with less clearly sinister material are going to complain about censorship.

There is plenty of official pressure that makes no pretense of routing itself through non-governmental groups. President Obama’s Sunday speech on terrorism included an explicit promise to “urge high-tech and law enforcement leaders to make it harder for terrorists to use technology to escape from justice.”

A senior administration official told The Hill there is “a dialogue that we have been having with Silicon Valley” about “cases where we believe that individuals should not have access to social media” for recruiting terrorists and planning violent operations. However, the White House abandoned plans to call for legislation that would compel social media companies to take stronger measures against jihadis.

Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton also called for social media companies to “deprive jihadists of virtual territory” on Sunday, and was somewhat dismissive of concerns about how such an agenda would raise “all the usual complaints” about freedom of speech.

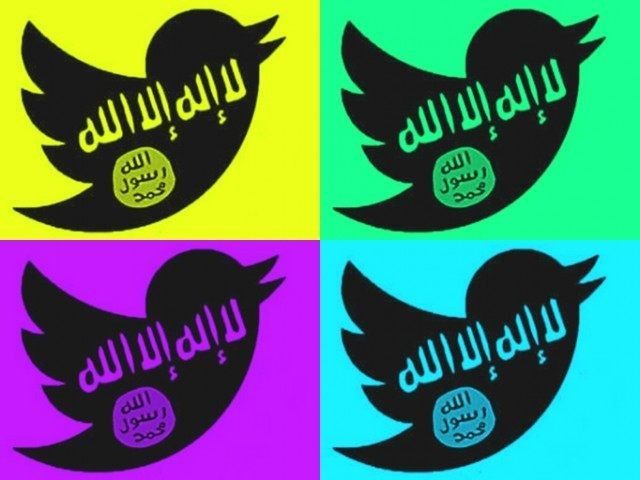

The impulse to drive terrorists off social media is bipartisan, as The Hill notes the House Foreign Affairs Committee has also urged Twitter to “put a stop to this cyber-jihad.” Aside from the most dedicated free-speech campaigners and intelligence analysts who use terrorist social media as a surveillance resource, just about everyone agrees the online footprint of terrorists – especially social media-crazed ISIS – needs to be reduced. However, it is not just those most-dedicated free-speech campaigners who worry that censorship weapons unleashed against the cyber-jihad could run out of control.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.