New reports show that Africa’s middle class is closer to 18 million people than the previously estimated 300 million. To make matters worse, they are all located in a very small area of the continent.

In 2011, the African Development Bank stated the middle class contained 313 million people. However, Credit Suisse’s 2015 Global Wealth Databook put the number at 18 million, which is almost seventeen times smaller. Scholar John Campbell said the difference in numbers comes from the evaluations. The bank measured the classes with “income or consumption-related criteria” while Credit Suisse used “assets and wealth accumulation.”

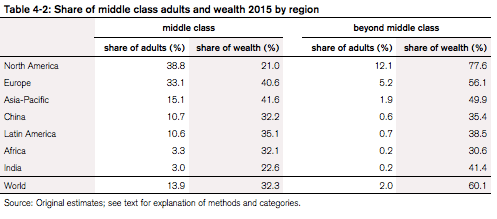

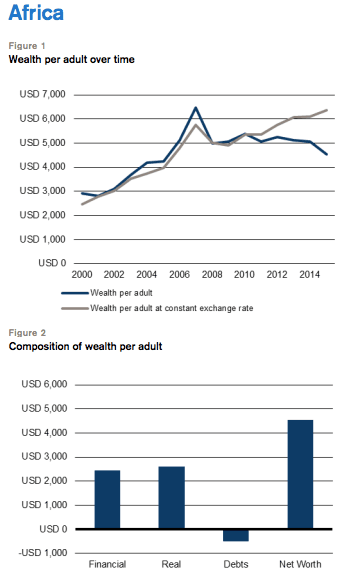

“More than 93% of adults in Africa own less than USD 10,000, and 95% of adults in in India fall in this range,” stated the authors.

One major puzzle for experts continues to be why the upper classes do not contribute to the profit of “multinationals,” instead preferring local companies. This has forced large companies who would bring jobs to more communities to limit their presence in many countries. For example, Cadbury and Coca-Cola closed factories in Kenya, and Nestle SA cut jobs by 15% in sub-Saharan Africa earlier this year.

“We thought this would be the next Asia, but we have realised the middle class here in the region is extremely small and it is not really growing,” said Cornel Krummenacher, the CEO of the region.

However, African companies are also not immune. At one time, South Africa’s ShopRite Holdings wanted 600-800 stores in Nigeria. But now they only have 12. CEO Whitey Basson said the companies cannot compete with informal traders.

“We just couldn’t compete with the informal trade,” he said. “It’s just a waste of time for us to expand in a market where we can’t get the optimum size for having enough stores to make a meaningful contribution to us.”

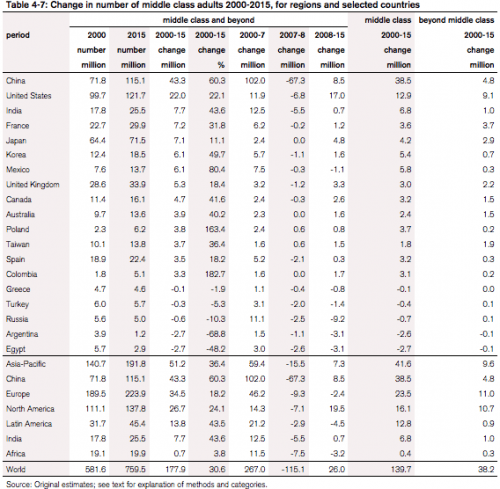

A Pew Research Center report from July found that African countries declined the most from 2001 to 2011. Ethiopia’s middle class dropped 27%, while Nigeria’s went down 18%. The researchers determined their statistics by classifying those who live on $10-$20 a day. Overall, their study concluded only 6% of Africa’s population can be considered middle class.

Mail & Guardian Africa reports:

The researchers’ [Credit Suisse] set $50,000 as the lower threshold for one to be classified as middle class, while the upper limit is pegged at $500,000, using 2015 prices. It is not arbitrary: the lower band is equivalent to about two years median earnings in the US, enough to tide over a member of the middle class in the event of any setback.

The upper figure is an estimation of what it would cost to buy an annuity (such as social security or pension plans) for one close to retirement that would pay the median wage for the rest of their life, while still leaving them solidly middle class.

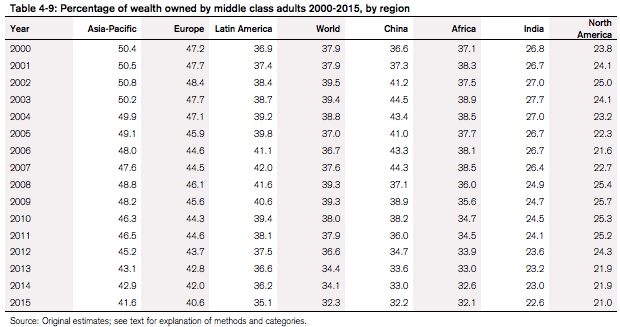

“Residents of Africa are also heavily concentrated at the bottom end of the wealth spectrum: half of all African adults occupy the bottom two global wealth deciles,” wrote the Credit Suisse authors. “In sharp contrast, North America and Europe are heavily skewed toward the top tail, together accounting for 63% of adults in the top 10%, and an even higher percentage of the top percentile.”

South Africa houses 4.3 million of Africa’s middle class. However, the number becomes “14.1 million if other countries such as Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco and Nigeria are thrown on the pack.”

“This means that the reminder of the middle class, which is about 4.7 million are shared between more or about 48 countries on the entire continent,” wrote Jonathan Adengo at AllAfrica.com.

CNBC Africa explained the importance of the middle class:

‘Middle class’ households are typically defined as those that spend at least half of their income on goods and services beyond just food and basic necessities. The emergence of this ‘consumer class’ helps to propel growth to the next level. Buoyed by supportive demographics, a rising middle class will mean that demand grows, businesses prosper, employment increases and economies flourish. It’s a virtuous cycle.

Traditionally, the ‘middle class’ has also played an important role in political developments. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the rise of multi-party politics in the 1990s, with calls for greater accountability, was often closely correlated with improved economic management and faster growth.

Jeremiah Mutonga, the African Development Bank (AfDB) Uganda country representative, echoed the exact thoughts of CNBC Africa. He said a large middle class economy is a need for Africa since they demand “good governance and accountability from those in power but beyond that it can also demand for quality goods and services.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.