China’s talk of cyber-security reform has not been followed by significant action, according to U.S. intelligence officials. “We haven’t seen any indication in the private sector that anything has changed,” said National Counterintelligence Executive William Evanina on Wednesday, as he announced a forthcoming report on economic espionage in cyberspace.

In fact, as Bloomberg Business reports, Evanina said the U.S. intelligence community doubts China could call an abrupt halt to its cyber-espionage if it wanted to, comparing such a dramatic change to “turning off a big faucet in China.”

One reason for the difficultly of China controlling its hackers is the diffuse nature of their cyber-espionage operation, which uses both regular People’s Liberation Army militarized hackers and irregular, deniable data-raiders who can be denounced as “rogues” at Beijing’s convenience. It takes time to filter instructions through that sort of network.

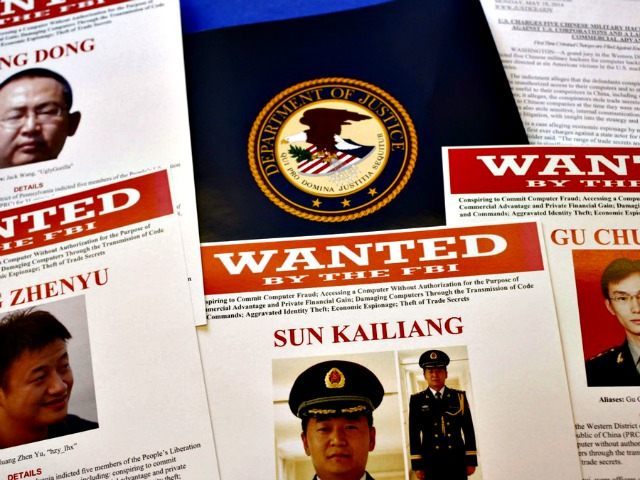

Also, as Bloomberg Business recalls, it was only in September that President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a mutual agreement to refrain from online economic espionage, activity China has resolutely denied engaging in, even though the U.S. indicted five Chinese military officials for stealing American corporate secrets last year. It would be rather embarrassing for China if hacking suddenly stopped within a few weeks of Xi agreeing in public to knock off the sort of activity he insists his country has never conducted.

However, the fact that Evanina’s office has detected little improvement in the Chinese hacking situation poses political difficulties for the Obama Administration, which may face increased pressure to “punish Beijing, possibly by placing new sanctions on companies and officials involved in hacking attacks,” according to the Bloomberg report.

The dimensions of the problem will be made clear in December’s economics espionage report, which was prepared with the assistance of 140 U.S. companies, half of which claim to have been targeted by foreign hackers. 90 percent of those attacks are said to come from the Chinese government, inflicting an estimated $400 billion in total economic damage.

Reuters quotes Evanina saying most of these intrusions are variants of the “spear-phishing” attack, which uses personal data about the targets to trick them into opening malware-laced emails, or simply give up security information about themselves that can be used to penetrate their computer systems. For example, Evanina mentioned the Office of Personnel Management hack as an example of spear-phishing, but according to most accounts it does not seem to have involved much in the way of viruses or aggressive computer “hacking” in the classic sense; the perpetrators stole valid credentials and logged into the system as seemingly legitimate users.

Also on the subject of the OPM hack, Evanina mentioned he was “unaware of any evidence that any parties had so far tried to use personal data hacked from OPM for nefarious purposes.” That is a relief to everyone who was worried about identity theft, of course, but it also supports the conclusion that foreign government hackers – specifically, Chinese government hackers – were behind the attack.

Rogue data pirates would have tried to sell the most valuable stolen data trove in history, or used it to carry out secondary crimes, such as credit-card fraud. They would have done it quickly, too, because such stolen data has a brief shelf life, especially when it’s the subject of intensive media coverage. Soon all the victims have changed their passwords, switched out their credit card numbers, and obtained other forms of protection, dramatically reducing the criminal value of stolen personal information. Its espionage value, on the other hand, does not decay so quickly; it can remain useful for identifying covert operatives and spying on government employees or contractors for years to come.

Stolen technology also remains useful for quite some time. According to Reuters, Evanina accused China of stealing “technology for producing glass insulation, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), drone aircraft, wind and solar power generation, hydraulic fracking and oil fracking,” among other prizes.

The agreement to refrain from cyber-theft between Presidents Obama and Xi has been embraced by the entire panoply of G20 nations, but there is still an awful lot of hacking going on. It is just too profitable, strategically useful, and deniable for state actors to disdain, no matter what public statements they make. The potential benefits are enormous – a glance at Evanina’s list of stolen technologies makes $400 billion in damage sound quite plausible – while the costs are virtually zero.

To date, no one has declared either a trade war, or the kind fought with bullets, over hacking offenses. China pulled off Cyber Pearl Harbor with the OPM hack, changing the espionage game for years to come, with no real consequences. Arguably, the opportunity for Xi to hold photo ops with President Obama and pontificate about China’s dedication to Internet security was worth whatever sanctions they could conceivably suffer. Thanks to the deniability inherent in operations that use “rogue” hackers, the worst-case scenario for active government cyber-saboteurs would involve rounding up the Usual Suspects and holding a show trial or two.

On the practical side, computer experts have long lamented that defensive technology lags behind malware – the hackers always have an edge. Cyber espionage works, the risks are minimal, and the benefits are great, so it’s going to keep happening.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.