Clambering to the crest of a ridge named Mont Saint-Jean on the early morning of June 18, 1815, the solitary figure who raised a looking glass to his eye probably was not thinking about the future of western civilization. For that British commander, victory on the rain sodden fields below him only represented what he hoped would be the final check on the territorial ambitions of the French adventurer who had convulsed Europe in war for over 15 years.

Yet the Duke of Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte on the field of Waterloo two hundred years ago, did indeed have a bearing on the course of western civilization, but not because it sealed the fate of just one man.

The Battle of Waterloo, in fact the entire series of Napoleonic Wars, represented the climactic struggle between absolutism on the one hand and an emerging liberal democratic tradition on the other–a struggle commenced when a British monarch grudgingly applied his royal seal to a document known to history as the Magna Carta.

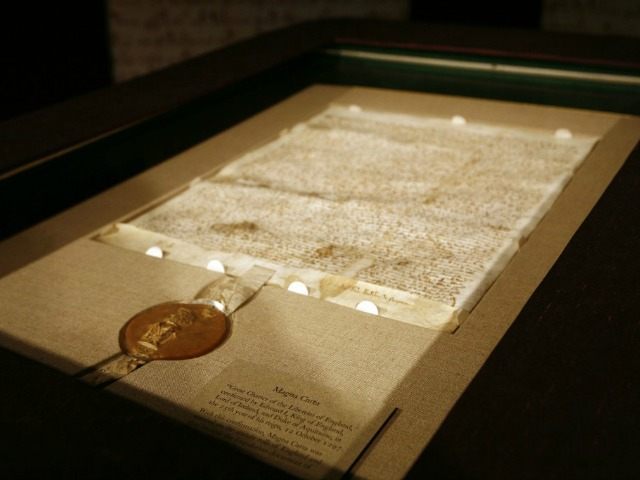

It is one of the strange quirks of history that in the same week Bonapartism was delivered its death blow in a Flanders field, the British celebrated the 600th anniversary of the signing of one of their founding documents. That Charter, 63 clauses in length, many of which we today might regard as governing trivial matters, was the culmination of a centuries-long attempt to check the power of the King, ensuring that royal fiat did not encroach on long held and much cherished individual rights. The baronial authors of the Magna Carta were not thinking of posterity nor of protecting anything other than what they regarded as their own feudal prerogatives. But in confronting the King under threat of civil war, they took the most forceful non-violent action by any peoples in Europe until that time to emphatically state that the King was answerable to not only his people but also to the law–and that he would not be permitted to stand above either.

It would take many more centuries for this idea to gain currency in mainstream continental thinking and when it was finally (and violently) brought into force, it was only a matter of years before the Europeans, most notably the French, regressed back into absolutism.

France, in particular, would not be done with its giddy embrace of authoritarianism. From the fall of Napoleon, to the rise of his nephew Napoleon III, to Vichy France, to the centralization of power that typifies the European Union today (and is remarkably undemocratic) we can see how the island kingdom of England really did part ways with its continental cousins, for whom constitutional monarchy and parliamentary rule were in truth mere abstractions to which one paid lip service–rather than deterministic features cemented into the very tissue of their political structures.

Many commentators and scholars have written authoritatively on how and why the concept of individual liberty flowered in England; but it is more instructive to note the way in which this idea pollinated, radiated from its source and then came to dominate the world. Carried with the Pilgrims to the first settlements in the New World; borne on the convict ships which reached Sydney Harbor, sailing with merchant seamen who braved the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the British determinedly transferred their ideas of individual liberty and freedom to the countries they populated giving birth to the Anglosphere and becoming the de facto leaders and guardians of what today we regard as Western civilization.

Is it any wonder that the American revolutionaries in the 1770s, in claiming their rights to reject taxation without representation, regarded themselves as doing so not as Americans at all but as British citizens, whose natural rights, they claimed, had been articulated and codified in the Magna Carta.

Today there are many who wish to characterize the Magna Carta as irrelevant, as representing nothing more than a back room deal between a crooked king and his cronies which the King almost immediately repudiated anyway.

What they fail to understand or appreciate is that history swept the Magna Carta forward as a blueprint upon which future generations would leave their own designs, using it, over time, to erect impregnable structures which would guarantee such rights as due process, equality before the law, and habeas corpus–rights which have come to be regarded, even in the halls of that broken institution the United Nations, as universal.

None of this appeared to be at stake amidst the cannon’s roar at Waterloo. But nearly a century and half later, when the Western democracies confronted absolutism’s latest continental incarnation, no one could be in any doubt. It fell to the English speaking people to defend and save the West. That role is no less incumbent upon us today and in face of the rise of a reinvigorated, militant Islam, Russian tyranny, Europe’s reversion to statism, and our own intellectual elite’s growing rejection of Western exceptionalism,we shirk that responsibility at our peril.

Avi Davis is the President of the American Freedom Alliance in Los Angeles. John L. Hancock is the author of Liberty Inherited (CreateSpace, 2011) and a fellow of the American Freedom Alliance. They are the co-ordinators of the international conference Magna Carta: The 800 Year Struggle for Human Liberty ( Los Angeles – June 14 -15)

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.