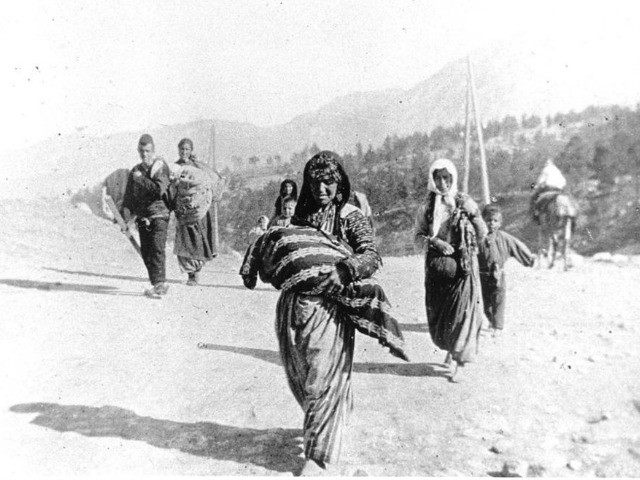

On April 24, 1915 the Ottoman Turkish leaders ordered the arrest of hundreds of notable Armenians in Istanbul and launched the systematic annihilation of Armenian as well as Assyrian Christians within the empire’s borders and throughout the Middle East. This day would become known as “Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day,” and a century later is the center of a persistent geopolitical controversy.

In 2006, then-Senator Barack Obama penned a letter to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice urging her to recognize the deaths of 1.5 million Armenians in the early-twentieth century as a “genocide.”

Citing a number of studies, scholars, and eye-witnesses of the massacre in Armenia, Obama wrote, “The occurrence of the Armenian genocide in 1915 is not an ‘allegation,’ a ‘personal opinion,’ or a ‘point of view.’ Supported by an overwhelming amount of historical evidence, it is a widely document fact.”

Though Obama was insistent that the George W. Bush administration use the word “genocide” when referring to this incident, he has failed to keep his word from a pledge he made during his 2008 run for president. Many expected Obama to use the 100th anniversary of the genocide to keep his promise, but the president has decided to refrain from mentioning genocide in his Remembrance Day comments.

President Obama was mostly accurate in stating that there is a great deal of support for the conclusion that genocide was committed on the Armenians. Some Turkish scholars refute that genocide took place and lay the blame of the slaughter at the feet of the Armenians themselves. However, this can largely be attributed the long-standing Turkish tradition of denying the events took place and the increasing belligerence toward individuals and nations who say otherwise. Though the undisputed mass killing of Armenians began during World War I, the conflict between the Armenians and Ottoman Turks had roots in earlier conflicts.

At the outset of World War I, the Ottoman Empire was crumbling and beginning to tear apart on ethnic and religious lines. The Ottomans were also under threat from European imperial powers which had become involved in the Middle East. Nationalist Armenian movements that tried to court European sympathy, and Russian interest heightened the Turkish belief that the Armenians scattered throughout their empire were a disloyal threat.

In the recently-released book, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, historian Eugene Rogan explains in-depth the roots of the Armenian genocide.

Several Armenian nationalist organizations, the Hunchaks and Dashnaks, made attempts in the 1880s and 1890s to build ties to Great Britain and Russia and push for Armenian independence. This movement was met with repression by the Ottoman authorities, and there were a series of massacres committed against Armenians in 1894 and 1896 in which hundreds of thousands were killed.

“In 1909, many Ottoman Turks suspected the Armenians of being a minority community with a nationalist agenda, intent on seceding from the empire,” Rogan wrote. However, the Armenians would have difficulty coalescing into a separate nation because they were not geographically concentrated. Rogan continued, “Without a critical mass in one geographical location, the Armenians could never hope to achieve statehood—unless of course, they could secure the support of a Great Power for their cause.”

There was a movement to to compromise between the Turks and Armenians that could have prevented later strife—full citizenship rights granted to Armenian Christians as well as a decentralization of Ottoman authority—but these “hopes were dashed in the aftermath of the 1909 counter-revolution when, between 25 and 29 April 1909, some 20,000 Armenians were killed in a frenzy of bloodletting,” according to Rogan.

The outbreak of World War I was very bad timing for the Ottoman Empire and the Armenians. The war got dragged into the Middle East as Germany tried to bolster its ties to the Ottomans and Great Britain and Russia tried to check their influence.

Armenians served throughout the Ottoman military, but were accused by fellow soldiers of siding with the Russians and enemies of the empire. Adding to the strife was the German-fueled call for global jihad by the Ottomans against their enemies. The result was that many Muslim Turks turned against their Armenian comrades and killed their fellow soldiers en masse with no repercussions. “Increasingly, Armenians were no longer seen as fellow Ottomans,” wrote Rogan.

In April of 1915 conflict between the Turks and Armenians became so great that rebellions broke out in Armenian communities and there was open conflict with Ottoman authorities. This set off a chain of events that lead to the genocide of Armenians. A Venezuela soldier of fortune who had been fighting with the Ottomans saw a brutal massacre of Armenians by Turkish troops. When the Venezuelan asked an Ottoman officer to cease the killing the officer responded acceding to Rogan, “that he was doing nothing more than carry out an unequivocal order emanating from the Governor General of the province [i.e. Cevdet Pasha]… to exterminate all Armenian males twelve years of age or older.”

The Turkish Committee for Union and Progress (CUP) often employed hired gangs and criminals to kill the Armenians and actively encouraged the slaughter, according to Rogan. He wrote about a Turkish captain’s confession, recounted to an Armenian priest, that government officials had sent soldiers to “all the surrounding Turkish villages and in the name of holy jihad invited the Muslim population to participate in the sacred religious obligation” of killing Christian Armenians.

In the years that followed, at least hundreds of thousands and likely over a million Armenians were killed. Some died simply as a result of war, but many others due to direct targeting from their fellow Turks and indirect targeting from Ottoman authorities. And the Turks engaged in more than killing; they systematically tortured the Armenians.

Lloyd Billingsly at FrontPageMag wrote, “Torture squads would apply red-hot irons, tear off flesh with hot pincers, then pour boiled butter into the wounds. The soles of the feet would be beaten, slashed, and laced with salt. Dr. Mehmed Reshid tortured Armenians by nailing horseshoes to their feet and marching them through the streets. He also crucified them on makeshift crosses.”

U.S. ambassador Henry Morgenthau Sr. wrote in his memoir, “Most of us believe that torture has long ceased to be an administrative and judicial measure, yet I do not believe that the darkest ages ever presented scenes more horrible than those which now took place all over Turkey.”

In 2006, Rice and some conservative commentators argued that stirring the pot and officially recognizing the Armenian genocide was not worth undoing the fragile relationship between Turkey and the United States at the height of the Iraq War. For instance, foreign policy analyst Fred Gedrich argued in National Review that if the House voted to recognize the Armenian genocide it could prompt Turkey to use force against U.S.-allied Kurdish rebels in northern Iraq, as well as deny access vital Turkish seaports to American troops and supply ships. But critically, he wrote, “Turkey serves as a bulwark against radical Islamic forces and is one of few Muslim countries having full diplomatic, economic and military relations with Israel.”

The Turkish authorities lashed out in 2007 and recalled their ambassador after the House voted to consider making an official recognition of Armenian genocide. Turkey has repeated this action recently when they recalled their ambassador from the Vatican after Pope Francis called the Armenian massacre the “first genocide of the 20th century.”

The last American president to call the incident in Armenia a genocide was Ronald Reagan, in a 1981 speech memorializing the Holocaust. This followed a long-standing tradition of Americans aiding the Armenian survivors of the massacre. In 1925, a massive rug woven by orphaned Armenian girls was given to President Calvin Coolidge in recognition of American efforts to help their people. Coolidge proudly hung this rug in the White House and took it to his home after he left office.

Though this rug was returned to the White House during the Clinton administration, Obama’s administration initially refused to release it to the Smithsonian for display.

Dr. Rafael Medoff, the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, wrote in a History News Network article, “President Coolidge had pledged that the rug would have ‘a place of honor in the White House, where it will be a daily symbol of goodwill on earth,’ but instead, in the autumn of 2013, it became a daily symbol of politics taking precedence over recognizing and combating genocide.”

After a great deal of pressure, the Obama administration allowed the rug to appear at the Smithsonian in a generic “gifts to the White House” section.

“The genocide rug was sandwiched in between a Sevres vase presented by France to the United States after World War One, and a cluster of lucite-encased branches sent by Japan after the 2010 tsunami,” Medoff wrote.

Many on the right and left still make the argument that officially recognizing the Armenian genocide is harmful to American national self-interest, a position that Obama’s actions give credence to in light of his failed campaign promise.

However, considering what has taken place in the Middle East since 2007, the United States may want to reconsider the strained attempts to remain in the good graces of a Turkey that has moved much farther in the direction of supporting enemies of the United States and the free world.

The Turks are currently amongst the world’s most anti-American people. A recent Pew survey ranked it as the third most anti-American country after Egypt and Jordan. The November 2014 attack by Turkish nationalists on U.S. Navy sailors was just the most recent prominent example of the level of anti-American sentiments in the country.

Islamist parties have consistently been on the rise in Turkey as has the focus on fundamentalist Islamic teaching in their schools. Turkey’s formerly close ties to Israel have evaporated since 2012. The American Jewish Congress rescinded its Profiles in Courage award given to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2004 after calling him “arguably the most virulent anti-Israel leader in the world.” There have even been accusations that Turkey has been funding the Islamic State and gives medical treatment to ISIS fighters.

The bottom line is that the need to tiptoe around Turkey’s insistence on never mentioning the Armenian genocide is quickly evaporating as the country becomes increasingly hostile to the West and works against American interests. While there may be no need to push for Congressional recognition of the Armenian genocide, a simple mention by the president a century later would have been a powerful statement. A statement would show that the United States will not continue to tolerate the horrendous mass-murder of Christians, Jews, and countless other people that is taking place throughout the Middle East today. Now that opportunity has been entirely missed as American power recedes and even the smallest appeals to moral authority disappear.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.