For years she was a mother of 10 young children, keeping a good, Muslim home. Now she is a rebel commander with a gun, fighting, she says, for her honor and her religion. Her children battle at her side.

Speaking in an on-camera interview with journalist Tracey Shelton, the 43-year-old muqatila, as such women soldiers are known, calls on others to join in her battle against Bashar Assad, and in the founding of a Syrian Islamic state. And though her all-female battalion numbers only 15 troops, she is by no means alone.

The role of women in the three-year-old Syrian conflict is complex and often confusing, but one thing is abundantly clear: women have become one of the strongest weapons in the war, used as much by the regime as by most of the countless rebel groups.

“Early on,” Shelton says, “women were used largely to smuggle weapons across the border in their abayas, since they are never examined at checkpoints.” But that role has changed as rebel forces have taken over most of the borders and as Syria has been ripped apart by death, torture, and terror from within.

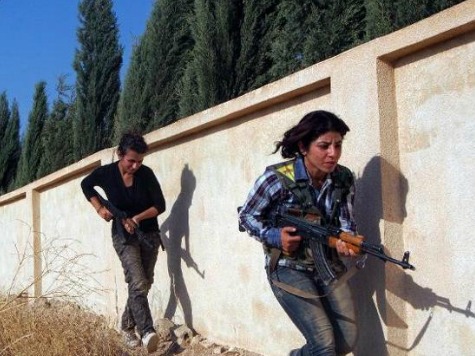

These days, they carry their own Kalashnikovs and know how to use them. Some are well-trained snipers. And while most women continue to fulfill traditional wartime roles – cooking meals, nursing the wounded – more and more of the estimated 5,000 women known to have joined this war are on the front lines, fighting alongside men.

Many of these women have come to Syria from abroad – and the number of those women is growing, Edwin Bakker, a fellow at the International Center for Counter Terrorism in The Hague, told me in an e-mail.

Some say that the trend started with Assad’s Lionesses for National Defense, an all-female paramilitary force that the Syrian leader established in 2012. Others point to women fighters in the Kurdish militia group Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), where one in every five fighters is a woman. And secular women–university students and professionals–have been taking part in the revolution in one way or another from the beginning in the major cities, though there is no knowing how many of those first rebels have become actual combatants. Indeed, Shelton observes, “A lot of the secular fighters who started the revolution have had to flee because they are afraid of Al Qaeda and ISIS, (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria).”

But the presence of women fighters among Islamist groups is new, and while few in number, represent a disturbing development: women who are willing to violate the very principles of Sharia to build a Sharia state for the future.

“In Arab countries – and Libya and Syria more than other Arab countries – men have the feeling they have to protect the women,” says Shelton, “so for them to be out there fighting – it’s not that they’re not willing or don’t want to, but it’s difficult for them to convince husbands to let them come to the front line.”

But not always, especially for the European women. British-born “Myriam,” as she is called in a British Channel 4 documentary, first went to for Syria to wed Swedish-born Abu Bakr in an arranged marriage. While her new husband, himself a foreign member of the Islamist forces, initially refused to allow her to take part in the fighting, he eventually relented; the documentary shows the couple comparing “his and her Kalashnikovs.”

“When I’m shooting my one, it’s better than shooting your one,” she says.

Other British women reportedly have joined the fighting. In January alone, two teenage girls were arrested at Heathrow airport on suspicion of links to terrorist activity in Syria, while two others were charged with helping to finance the rebel forces.

What is it about the Syrian conflict that draws so many women–women who never considered fighting in Afghanistan or Iraq?

In part, according to Bakker, it’s a geographical issue: Syria is easier to get to from the West than is, say, Afghanistan–it is just a walk across the Turkish border. Difference in religious beliefs among the Taliban and that of Western Salafi women also plays a role, he says. “And I am sure this also played a role for western Muslim women: the lack [in Afghanistan or Pakistan] of basic facilities and any luxury.” And, he adds pointedly, “the impact of social media cannot be underestimated.”

But there are emotional elements as well. Ongoing media reports of the suffering of children or of other women, raped by Assad’s forces, inspire rage as much as they do a longing to give help to those in need. Others, says Bakker, “come to Syria as part of a dream to live in a truly Islamic State under sharia law and raise their children in a future heaven on earth.”

Yet because the phenomenon of women fighting on the frontlines is so new, many journalists and experts I spoke to expressed skepticism. Both Shelton and former CNN Iraq Bureau Chief Jane Arraf, who has also reported extensively from Syria for Al Jazeera, told me they never encountered these women fighters–nor had they met anyone else who did. And Edwin Bakker maintains that the idea of Islamist female fighters “does not fit with their culture, ideology and their modus operandi in the past (unlike Kurdish female fighters or secular Arab women). Islamist women have played a role as suicide bombers. But the idea that they would fire at the enemy side by side with male Islamist fighters is either a true novelty or propaganda.”

And yet, the UK’s counter-terrorism unit commander Richard Walton told the Standard, “We’ve had a number of teenagers both from London and nationally who’ve been attempting to go to Syria. That’s boys and girls, unfortunately. It’s not just the odd one.”

How to explain the differences? Are there, as the New York Times reported, 5,000 women fighting among the Syrian jihadists? Are many Westerners among them? Is the number of Western women growing?

That depends largely on definitions: how one defines “jihad” and what is considered “joining the rebel forces.” And on this, there seems to be some confusion. With the plethora of media reports, one gets the impression that every Muslim in Syria who is not supporting the regime is a jihadist, and that a jihadist is an Islamic terrorist. No distinctions seem to be made among Syrians who join secular groups on the frontlines, Kurdish women fighters, European converts who join moderate Islamic battalions, and those who may be connecting with Al Qaeda affiliates or the terrorist ISIS–an organization so extremely violent that even Al Qaeda has recently disavowed them.

At the same time, German intelligence officials have demonstrated a link between European aid organizations and jihadist groups, arguing that many Westerners who claim to be going to Syria assist in hospitals and provide other charitable aid in fact are allying with Islamists. Others seem to find themselves locked into Islamist groups when they’d only gone there to assist in humanitarian aid.

The boundaries, in other words, could not be more blurred.

This is not to say that a threat does not exist. Indeed, though Shelton told me she would “be surprised” to find women fighting with Al Nusra, Syria’s official Al Qaeda wing, she was less certain about ISIS. “You can’t get near them as a journalist, because they’ll kidnap you,” she said. “They’re very secretive. So these women may very well be going within ISIS groups, but no one sees them simply because they don’t mix with other groups.”

If that is the case, then should these women return to Europe, they will be bringing terrorist skills back with them- skills they are likely to teach their children. And with the ability still to hide their weapons beneath their abayas–weapons they are now fully trained to use–they may prove to be radical Islam’s most powerful weapon yet in its war against the west.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.