(Bagram, Afghanistan) On a grey-brown December morning, an Afghan Air Force C-208 taxis and holds short of runway two-nine at Kabul International Airport. Its mission isn’t glamorous: a liaison flight from the capital to the NATO Base at Bagram, up the Kabul valley to the northwest.

The pattern in Kabul is busy, and the 208 holds a full ten minutes, waiting its turn to take off. In the interim, a British C-130 is cleared to land and a pair of Afghan Air Force Mi-35 attack helicopters roll past and lift off, heading for an air-support mission somewhere near Gardez.

While the C-208 sits idling, the flight crew painstakingly goes through the departure checklist. In addition to ferrying passengers and light cargo to Bagram, this is a training flight. The plane and pilot are Afghan Air Force, but sitting in the flight deck’s right seat is thirty-year-old US Air Force Captain Lindsey Bauer.

Captain Bauer is part of the NATO Air Training Command-Afghanistan (NATC-A), a select group of pilots, aircrew, flight maintainers, security personnel and operational planners whose mission is to rebuild the Afghan Air Force.

Bauer normally pilots the KC-10 Extender, one of the US Air Force’s biggest tanker planes, an aircraft that dwarfs the single engine C-208 she guides down the busy taxiway.

After graduation from the US Air Force Academy and several deployments with KC-10 squadrons, Bauer volunteered for duty in Afghanistan and was selected as an advisor pilot with the 438th Air Expeditionary Wing. Her job includes basic and advanced flight instruction, as well as flying as a NATO ‘Mentor’ on Afghan air combat missions.

Flying with her today is a twenty-year-old Afghan Lieutenant, fresh from basic flight training in the United States. Like other Afghan service members interviewed for this article, he asked that his identity be protected. Despite a recent promotion, the flight student has yet to tell his family that he is part of the Afghan Air Force. In a country polarized by sectarian and political tension the Taliban has been known to target the family members of Afghan aviators. The risks this young pilot takes in the air extend to his relations on the ground.

But more encouraging–even inspiring–is the Afghan pilot’s attitude. On this afternoon sortie he is focused, enthusiastic, and well prepared. In the cockpit he listens as Captain Bauer discusses the intricacies of a Kabul departure. A modest C-208 isn’t likely to attract a shoulder-fired missile, but it is slow enough to be a lucrative target for rooftop gunmen. The take-off will be steep and spiraling, conveying plane and passengers quickly out of the cone of possible ground fire.

As the Afghan officer completes his checklist, the tower clears the 208 direct to Bagram.

“All right,” Bauer says into the intercom, “Let’s do a short field departure.” She turns over the stick, and the engine surges. “You have the aircraft.”

“I have the aircraft,” the Afghan lieutenant answers.

The C-208 turns onto the runway, straddles the centerline, and rolls for take off.

At its peak, the Afghan Air Force was a regional power with over 400 combat aircraft including dozens of MiG fighters and Sukhoi bombers. Schooled by the Russians, Afghan aircrew and flight maintainers were among the best trained in Asia.

Then came the Soviet withdrawal. In February 1989, Mikhail Gorbachev declared Soviet participation in the Afghan conflict to be at an end, but in the mountains and deserts north and east of Kabul, the fighting continued unabated. In the ensuing multi-lateral civil war, the decline of the Afghan Air Force was inexorable. Aviation fuels and lubricants became increasingly hard to find, and spare parts (even machine screws and batteries) became more precious than gold. As Mujahideen scourged the countryside, Afghan Air Force pilots and mechanics melted away from their bases and went into hiding. The jet fighters moldered away in hangars and revetments, and the few remaining helicopters were scattered between far-flung airfields, pressed into the service of warlords.

Eventually, the Taliban entered Kabul and declared an Islamic Emirate on September 27, 1996. But the Taliban’s victory had been pyrrhic and the prize hollow. Vast areas of the country remained under the control of the Northern Alliance. The city of Kabul was in ruins, its international airport a barely functioning collection of craters, and the Afghan Air Force had all but evaporated.

When US and coalition forces invaded in 2001, there were only a handful of flyable airplanes in the entire country. As Operation Enduring Freedom undertook the mission of pacifying the Afghan countryside, little thought was given to rebuilding the Afghan’s military aviation capability. It was four years before the decision was made to re-establish an independent Afghan Air Force.

The mission was daunting.

Aircraft could be supplied or purchased, but the backbone of a modern air force–flight crews, mechanics, and avionics technicians–had to be trained from almost from scratch. In 2005, this effort crystallized with the activation of the US Air Force’s 438th Air Expeditionary Wing. The pilots and maintainers of the 438th simultaneously conduct the daily training of Afghan air-crews and mechanics, as well as serve as in-cockpit “mentors” for Afghan air combat operations.

The Afghan Air Force operates American made workhorses like the C-130 and the C-208, but the mainstay of the force is an aging fleet of Russian-made transport and attack helicopters. Some, like the Mi-17 and Mi-24, are veterans of the Soviet-Afghan war. All perform vital transport and tactical missions in a country where the roads can change from safe to suicidal in the span of minutes.

It is the job of the NATO Air Training Command’s boss, Air Force Brigadier General John Michel, to oversee the instruction of Afghan aircrew and maintainers across this multi-platform, multi-mission effort.

“The withdrawal of most American forces in 2014 makes every training flight and mentored combat mission vitally important,” Michel said during a late night interview in his headquarters at Kabul airport.

Though a continued training presence for the Afghan Air Force is planned, General Michel knows that time is not on his side.

“Regardless of the Status of Forces agreement, US combat forces will continue to be drawn down as the Afghans stand up. When the Americans are gone, the Afghan Air Force will have to fly solo.”

An expanding air force needs aircrew, as well as mechanics, and the training pipeline for a pilot can be as long as three years. To speed this process, General Michel has assembled a hand-picked cadre of flight instructors. Team members are drawn from experienced US Air Force applicants, and special attention is given to pilots who have demonstrated flexibility, cultural awareness, and what General Michel calls “emotional intelligence.”

“Mutual respect is fundamental to building the trust of our allies,” General Michel says. “Everything we are trying to do follows from that.”

Unlike most American generals in Afghanistan, John Michel does not spend much time in “the bubble” of a command center. He leads from the front, literally, and spends many of his days out among the troops, talking to both his trainers and their Afghan charges on the flight line.

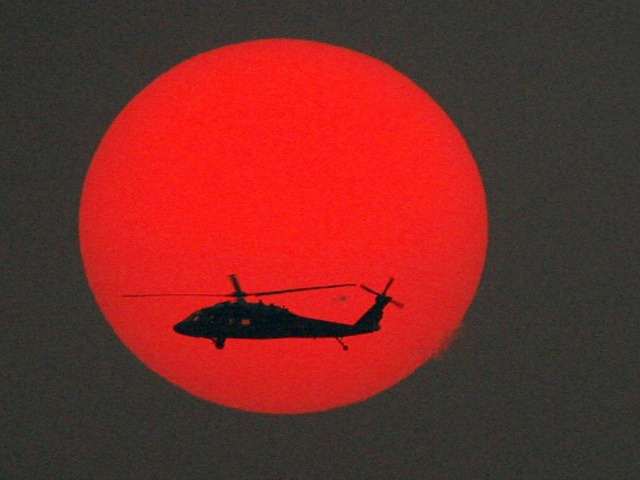

His security detail alert and discreetly following, General Michel talks with Afghan pilots as they prepare a pair of Hind gunships for an afternoon sortie. A few minutes later, he’s again out of his armored SUV, this time in one of the hangars, shaking hands with groups of Afghan mechanics. General Michel uses these visits to make sure that the wheels are turning smoothly, and he is not above tackling a problem directly.

It has previously been a characteristic of the Afghan Air Force that expertise and materiel have been used to build fiefdoms among aircraft maintainers and mechanics–a miniature game of empire-building based on know how and spare parts. It is part of the NATO mission not only to train a 21st century Air Force but also to rebuild the Afghan military’s internal dynamics.

An hour has passed since General Michel arrived on the tarmac for his unscheduled visit. After touring the hangars, the general enters the avionics shop and is buttonholed by a pair of maintenance officers. Someone, somewhere, has ordered the transfer of a couple dozen of their best technicians. The general listens closely as an interpreter explains the matter, a page straight out of “Turf Wars 101.”

With a series of handshakes, General Michel promises to stop the transfers until the matter can be looked into. This seems to please the crowd of avionics technicians who have gathered around. The flight maintainers go back to work, and the general heads back to the command center.

General Michel has made himself the face of the NATO air training effort; he is its brand, and he knows that trust is a fundamental component of the job he has come to do. This high-visibility, high-access leadership style is intended to foster confidence between Afghans and Americans–but this strategy is not without risk.

As elsewhere in Afghanistan, the threat of green on blue violence vastly complicates the work of American advisers. Thirty-six months ago, an Afghan pilot opened fire in a meeting, killing nine American officers and senior enlisted personnel. The Taliban, too, understands that the NATO air-training mission is vital to the survival of the Afghan Republic. In June, they launched a coordinated attack striking with a pair of suicide bombers while other gunmen raked NATC-A area with automatic weapons fire and rocket-propelled grenades. Just weeks ago, in December, a car bomb struck a wall near the compound, casting a mushroom cloud skyward and tossing flaming engine parts into the headquarters area.

Afghan air and ground forces are making gains in combat capability and mission readiness. The nation’s police forces are making slower progress but are improving. American trainers proudly point out joint Afghan Army and Air Force operations–missions that see Afghan helicopters deliver Afghan soldiers against Taliban strongholds. Presently, the Afghan Air Force plans and executes over 90% of its operational missions, an impressive accomplishment and a critical step toward building a fully independent force. As American forces withdraw from combat, the tactical importance of the Afghan Air Force will become decisive. The military history of the 20th century proves it is impossible to conduct a successful counterinsurgency effort without air power.

The winter sun is slanting off the mountains as the Afghan Air Force C-208 continues its flight to Bagram. In the cockpit, Captain Bauer has a moment to talk about her tour.

“My own take on the mission… I’m enjoying it. I work with a fantastic and eager group of Afghans who are all more than ready to defend their country… At the moment, that means moving passengers and cargo, or transporting medivac patients so they can be appropriately taken care of.”

Captain Bauer nods at her copilot, “But they all dream of flying bigger and better things.”

As one of the mission’s only female flight instructors, Bauer has had to work around some of the chauvinism endemic in male-dominated Afghan culture. Her calm authority and patient teaching style have won her many converts.

“As far as the female aspect, I noticed that they were at first a little cautious around me, but a lot of them tell me that I remind them of a sister or cousin,” she says. “I think some also feel the need to look out for me, like they do their own relatives.”

Bauer, who is from an Air Force family, is also an example to the several female pilots now training for the Afghan Air Force. “I have a special bond with the females, too. There was one who was so excited to fly with me because all she has ever seen are male pilots. She really appreciates having a female instructor to relate to.”

The radio crackles, and Bauer listens as her copilot contacts Bagram approach in slow and careful English. The base at Bagram, too, has recently come under attack, and she watches carefully as her student banks into a steep approach. The landing is flawless, and in a moment the 208’s doors are open and the offload begins. It will be a short turn around.

As the engine whines, passengers and cargo are quickly disgorged onto the ramp. From the cockpit, a smile and a thumbs-up comes from the Afghan officer as the 208 heads back onto the runway. Captain Bauer and her student have another mission to fly, and night is coming.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.