“No one has power with the wind to restrain the wind…” Ecclesiastes 8:8

In his most recent speech to the nation, President Obama urged the American people to support him should he choose to use extremely limited force to stop Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons. But first he would try to accept Putin’s help to disarm Assad of these weapons.

Unfortunately, neither the President’s limited strike nor Putin’s brokered disarmament are likely to succeed in ending Assad’s use of chemical weapons.

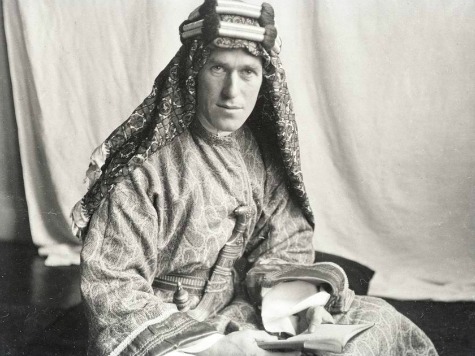

To understand why this is the case, it would be wise to view Syria’s history and culture through the eyes of famed historian and World War I era military commander T.E. Lawrence, whose exploits in the Middle East earned him the title “Lawrence of Arabia.”

Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom recounts his personal journey as strategic liaison between the British military and the Arab tribes that fought against the forces of the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

His account is part memoir, part military history, and part sociological study of the cultures of different peoples dwelling in the Middle East. Seven Pillars of Wisdom is a must read for anyone who wants to understand the needs of military leadership in the Middle East.

Lawrence’s experience with the region of Syria predated the events recorded in Seven Pillars. While pursuing his studies at Oxford during the summer of 1909, Lawrence went on a three-month walking tour of Crusader castles in Ottoman Syria.

He came to the Arab tribes as a cultural outsider, but his fresh eyes permitted him to gain helpful insights regarding the peoples he encountered on his campaigns. Lawrence loves and respects the peoples who are also the subjects of his study in Seven Pillars.

However, Lawrence gained his knowledge of these peoples in part by having to persuade them on behalf of his British superiors. Thus, in Seven Pillars we feel a tension inside Lawrence between being faithful to Britain and being faithful to the Arab tribes who stood at his side in battle. At several points he hints confessions of complicity in selling his allies down the river to be subjugated by Western powers.

Lawrence is careful not to characterize “racial stereotypes,” as we might use that term today. He is at pains to make clear that Syria is a Roman administrative designation, not the identity of a nation (a point that will become important to us later).

He prefers to talk of Syrians as “the peoples of Syria” emphasizing that these are really different peoples, with different goals, living in the same land. After explaining how he came to interact with Syrian factions, he begins with a general characterization of regional habits, while also distinguishing between different behaviors within the various cultures at the time. He writes:

All these peoples of Syria were open to us by the master-key of their common Arabic language. Their distinctions were political and religious: morally they differed only in the steady gradation from neurotic sensibility on the sea coast to reserve inland. They were quick-minded; admirers, but not seekers of truth; self-satisfied; not (like the Egyptians) helpless before abstract ideas, but unpractical; and so lazy in mind as to be habitually superficial. Their ideal was ease in which to busy themselves with other’s affairs.

From childhood [the peoples of Syria] were lawless, obeying their fathers only from physical fear; and their government later for much the same reason: yet few races had the respect of the upland Syrian for customary law. All of them wanted something new, for with their superficiality and lawlessness went a passion for politics, a science fatally easy for the Syrian to smatter, but too difficult for him to master. They were discontented always with what government they had; each being their intellectual pride; but few of them honestly thought out a working alternative, and fewer still agreed upon one.

This is not a kind characterization, but it should be kept in mind that he is analyzing the peoples of Syria through the lens of military purpose. Lawrence traces the lack of unity among these peoples to voluntary tribalism.

“In settled Syria there was no indigenous political entity larger than the village, in patriarchal Syria nothing more complex than the clan; and these units were informal and voluntary, devoid of sanction, with the heads indicated from the entitled families only by the slow cementing of public opinion. All higher Constitution was the imported bureau-system of the Turk…

Lawrence then draws attention to the provincialism of the peoples of Syria, and how ambitious Syrians or foreign powers took advantage of this provincialism to accomplish the ends of their nefarious perfidy or naïve altruism.

The people, even the best taught, showed a curious blindness to the unimportance of their country, and a misconception of the selfishness of great powers whose normal course was to consider their own interests before those of unarmed races. Some cried aloud for an Arab kingdom. These were usually Moslems; and the Catholic Christians would counter them by demanding European protection of a thelemic order, conferring privileges without obligation. Both proposals were, of course, far from the hearts of the national groups, who cried for autonomy for Syria, having a knowledge of what autonomy was, but not knowing Syria; for in Arabic there was no such name, nor any name for all the country any of them meant. The verbal poverty of their Rome-borrowed name indicated a political disintegration. Between town and town, village and village, family and family, creed and creed, existed in some intimate jealousies sedulously fostered by the Turks.

Lawrence understood that Rome named Syria “Syria” because it understood what Syria was. For millenniums, Syria has been a region of changing factions. Lawrence predicts this will continue.

Time seems to have proclaimed the impossibility of autonomous union for such a land. In history, Syria had been a corridor between sea and desert, joining Africa to Asia, Arabia to Europe. It had been a prize-ring, a vassal, of Anatolia, of Greece, of Rome, of Egypt, of Arabia, of Persia, of Mesopotamia. When given a momentary independence by the weakness of neighbors it had fiercely resolved into discordance Northern, Southern, Eastern and Western ‘kingdoms’ with the area at best of Yorkshire, at worst of Rutland; for if Syria was by nature of vassal country it was also by habit a country of tireless agitation and incessant revolt.

Today, Syria is Putin’s vassal. Assad understands what he governs, as he explains to Charlie Rose at the end of the clip below.

In his classic work, The Prince, Niccolo Machiavelli teaches that when a ruler chooses to act with brutal force he must move quickly, decisively, and then be done, or else his people will hate him.

But Assad is ruling Syria. He knows why Rome gave it its name, and he’s okay ruling over it with an iron fist. He has killed a great many to stay in power.

But he also knows his weapons are what keep him in power. With a multitude of other interests in his region, all exploiting the factiousness of the peoples of Syria, Assad would be a fool to hand over his most potent weapons.

Perhaps Assad would give them up if Putin promised to keep him in power. But Assad knows he is only valuable if he can remain in power. And from that tension arises the problem of whether it is feasible in reality that Assad would give up his chemical weapons. This whole debacle with Obama’s “red-line” has proven that America lacks the will to intervene. If Assad can use his weapons with plausible deniability, could he keep them? If Putin makes his calculations based strictly on his own national interest, which it appears Putin does, Assad very well might. Would chaos in Syria with an uncertain resolution be more useful to Putin?

The limited strike that President Obama has described is not feasible. This is evidently demonstrable through a careful analysis of all three levels of military campaign planning: the (1) Tactical, (2) Operational, and (3) Strategic levels. If we think carefully about each of these levels of war, and consider the President’s words, we should be confidently skeptical of any promised military or political gains from a limited strike.

So whether he orders extremely limited strikes or works through Russian diplomacy, do not expect the President to succeed in disarming Assad of his chemical weapons. Syria is Syria.

Lawrence of Arabia understood the peoples of Syria, and we should hear his warning. America can send desert storms, but one wind cannot control another. There will be no lasting peace for the peoples of Syria. Not any time soon.

Dr. Michael Collender did his doctoral research in how metaphor and narrative model complex systems in neuroscience and economics. He has been a Visiting Fellow in the Philosophy Institute at the Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium, and has researched and lectured at the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, VA. For more resources subscribe at SolveWickedProblems.com and follow @mcollender.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.