On the outskirts of a sleepy West Virginia town lives 92-year-old Frederick Mayer. His current life is fairly peaceful–he still chops wood nearly every day and volunteers with Meals on Wheels.

But this ninety-something’s life hasn’t always been so simple.

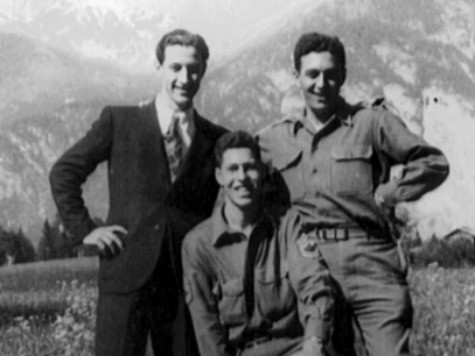

During World War II, he led one of the greatest missions of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Mayer’s incredible story provided the basis for my book They Dared Return: The True Story of Jewish Spies Behind the Lines in Nazi Germany.

Now, a new History Channel film, The Real Inglorious Bastards, returns to the true story chronicled in the book and captures Mayer’s amazing exploits in historically accurate detail. On May 7, an invitation-only screening of the film will open the GI Film Festival with a Congressional Reception at the U.S. Capitol Building to honor the veterans of the mission, including Mayer.

Mayer, who is Jewish, and his family fled Germany at the onset of the war, barely escaping the holocaust. But unlike other refugees, Mayer decided to return to German-occupied Europe to strike back at the very individuals who imprisoned some of his family members in concentration camps. He parachuted into the Third Reich, where he impersonated a German officer, blew up trains, sent back intelligence on Hitler’s bunker, and even accepted the surrender of Innsbruck, Austria. Mayer was motivated by a powerful combination of hate and love–hate toward the Nazis and love for America.

Mayer originally volunteered for the U.S. Army, but they rejected him as an “enemy alien.” However, the OSS, the forerunner to the CIA, saw Mayer’s potential and recruited him to join its ranks. He entered their German Operational Group (OG), precursors to the U.S. Army Green Berets, an elite team of commandos that would operate behind the lines in German-occupied Europe.

The OG group shared a unique bond. They all spoke German, and many were Jewish refugees who wanted vengeance for their families’ suffering. One recruit summed up the band of desperadoes: “The whole bunch were the craziest people I ever met in my entire life.”

In the summer of 1944 after extensive training, the OGs received the call to duty. They traveled by ship to North Africa.

There was only one problem–they got dropped off at the wrong port.

That didn’t stop the intrepid OGs. One of the mainsprings of the group spoke eight different languages, had fought and escaped from the French Legion, and had previously worked as a maître d’ at the Copacabana nightclub. He put his unusual skills and experience to work, selling surplus Army towels and other gear to Bedouins. With the cash, the group purchased train tickets to an OSS spy base in Algiers.

After unexpectedly arriving at the OSS post, the men sat and languished for months, waiting for a mission. Eventually, they transferred to Italy and once again continued to sit out the war.

Fred Mayer and his five Jewish cohorts, who had become best friends during the training, had had enough. They purloined a Jeep, mutinied from the OGs and arrived at OSS’s Secret Intelligence (SI) section, which had been dropping agents deep inside Nazi Germany. Nearly all the section’s missions to this point had been abysmal failures, leading to the death or capture of the OSS agents, and several agents ended up in Germany’s most infamous concentration camps.

Undeterred by the unit’s previous record, Mayer and his friends approached the unit’s commander, Lt. Alfred Ulmer, and begged to sign up.

Ulmer asked several pointed questions about their background, and the men revealed that they were Jewish. He asked if they were willing to kill. Finally, Ulmer asked the Jewish-Americans matter-of-factly, “Do you appreciate what can happen to you if you’re caught?”

Mayer responded, staring directly into Omer’s eyes, “This is more our war than yours.”

For the next several months, Mayer and his best friend Hans Winberg went about planning Operation Greenup. Their task was to penetrate one of the most secured areas of the Third Reich, an area of Austria near Innsbruck, where Nazis reportedly had been fortifying and massing vast quantities of troops and supplies.

The other objective was to identify rail traffic travelling from Innsbruck to Italy through the Brenner Pass.

The two men needed a third teammate who spoke German and knew the area–and was willing to risk certain death if captured. The OSS went to the only available source of that nearly impossible combination: an Allied prisoner of war camp. Feigning the role of a captured German POW, Fred entered a camp and networked within its gates. He found and recruited deserter-volunteer, Franz Weber. A former German commando and officer, Weber had fought on the Eastern Front but now was convinced that it was his duty to defeat the Third Reich for the sake of his country, Austria.

After training for months and mapping out the mission in minute detail, the men were ready to go–but no one wanted to fly the team. Finally, an intrepid American Air Corps pilot, Lt. John Billings, and his crew stepped forward and volunteered. Avoiding roaming German fighters, flak, and forceful Alpine winds and backdrafts, Billings threaded through 9,000-foot high canyon-like mountains and found the drop zone.

In a scene that could have been ripped from the movie Where Eagles Dare, the team, clad in white ski parkas, parachuted onto the side of a 9,000-foot glacier. The wrong tug on their chutes or a miscalculation of the pilot by mere seconds could have sent the men to their deaths.

After tramping through chest-deep snow, the men literally sledded down the side of the glacier in a Santa Claus-like sleigh. They approached speeds of 60 mph or more as the craft careened down the mountain. Mayer recalls, “It was the ride of my life. It was the scariest part of the entire mission.”

Once at the bottom of the mountain, the men boarded an Innsbruck-bound train infested with Gestapo. Weber bluffed his way past a team of agents that had been searching the train.

“Your papers?” the agent asked.

“We’ve already been checked,” Weber asserted with great chutzpah.

So convincing was his performance that the agent turned away from the team and started checking the papers of the other passengers.

After reaching a small town outside Innsbruck, the Greenup team set up camp. Mayer donned Weber’s old uniform and took on the cover story of a recovering German officer at the local hospital where Weber’s sister was a nurse.

In scene straight from Inglourious Basterds, Mayer sat at the bar with a bandage on his head, swilled beer, and listened to the stories of other recovering German officers. One, an engineer, had worked on the German Fuhrer’s bunker in Berlin. Mayer radioed the exact location and dimensions back to headquarters. (The original radio transcripts are preserved at The National Archives in College Park, Maryland.)

Mayer then pushed into Innsbruck, determining the schedules for troop and munitions trains bound through the Brenner to Italy. He called in air strikes, destroying dozens of them.

Later, Mayer changed his disguise and donned the clothing of a French electrician. He penetrated a secret underground factory producing jet engines for the Third Reich.

But after several weeks behind enemy lines that provided reams of actionable intelligence, a knock on the door of Mayer’s safe house changed his life.

Bursting through the door and into the room, a dozen Gestapo agents, armed with MP-40 machine pistols, quickly surrounded and apprehended Mayer. For the next three days, he was mercilessly beaten, tortured, and hung upside down. The Germans even broke his teeth with a powerful haymaker punch while stuffing a pistol in his mouth.

However, using his own guile, wit, and a fortunate set of circumstances, Mayer turned the tables on his captors.

It was April 1945, and Germany was finished. His captors, including Franz Hofer, the governor of the Alpine Redoubt and an immensely powerful man within Hitler’s inner Circle, faced war crimes prosecution. Mayer convinced Hofer the war was over. Without making specific promises, he offered salvation.

The governor was about to go on the radio to tell his troops to fight to the last man. But at the radio station, Mayer persuaded the Nazi to declare Innsbruck an open city, and place himself under his arrest, effectively surrendering the city and his forces to Mayer.

In one of the most incredible scenes from World War II, Frederick Mayer approached the American lines and informed the advancing 103rd division that the Germans had surrendered Innsbruck to him, saving potentially thousands of German and American lives in the process.

In an amazing turnabout, Mayer received an opportunity for revenge. The Gestapo agent that had mercilessly beaten him was taken to the very cell where he had tortured Mayer. Cowering in the corner, the agent was terrified to see his former captive. Trembling, he stammered, “Do anything you want to me, but don’t hurt my family.”

The mission that began with vengeance ended with forgiveness. A sense of calm came over Mayer, and he looked directly into the eyes of the Gestapo agent.

He responded, “Who do you think we are, Nazis?”

Mayer then turned his back on the agent and the war, refusing to speak about it for decades. During World War II, the OSS twice nominated Fred Mayer for the Medal of Honor. I made the argument for the medal in my book They Dared Return, and now Sen. John Rockefeller is championing the cause.

In an era of fake heroes who vie for their own reality television shows, Fred Mayer shies away from publicity. Not surprising to those who know him, Fred Mayer may not attend the Congressional reception and the screening of the movie chronicling his feats. He’s already seen the movie. Besides, “it’s too late,” he says of the event. “I don’t stay up late anymore.”

When you’re a World War II hero, you can do whatever the hell you want.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling author and combat historian who has conducted over 5,000 oral history interviews with heroes like Frederick Mayer. His books that capture Mayer’s story are They Dared Return and The Brenner Assignment. He has written eight books, including his most recent (insrt embedded link to Amazon) Dog Company: The Boys of Pointe du Hoc: Rangers Who Accomplished D-Day’s Toughest Mission and Led the Way Across Europe. His website is http://www.patrickkodonnell.com/.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.