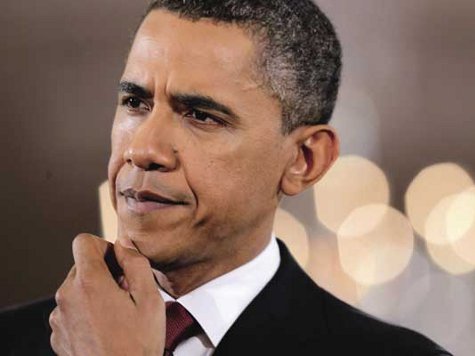

Syria’s sectarian civil war is entering its second year, with 15,000 to 19,000 estimated casualties so far. President Obama has intervened in the conflict diplomatically and has expressed a willingness to get involved militarily.

The makeup of both sides is only now becoming clear, the most recent revelation being that Iran has Revolutionary Guard troops on the ground inside Syria. And there has been no desired objective articulated beyond the removal of Assad and the current government. There is no indication that the humanitarian component of the crisis would be alleviated by the removal of the Assad regime; in fact, the opposition forces are dominated by Islamist extremists, Al Qaeda, and their supporters. Democracy is an unlikely organic outgrowth of the largely sectarian conflict.

The willingness to intervene in the civil conflicts of nation states without a direct national interest and attempting to add a moral component to the intervention checklist is a departure from established American foreign policy. Traditionally, American intervention has been based upon principles of strategic interest and maintaining a balance of power within a region. Western policy historically ignores internal politics and restricts intervention to violations of borders or international boundaries. External intercession on the basis of sectarian or democratic issues, or demands for negotiation for the purpose of the transfer of power within a functioning state, have not been a feature of American foreign policy prior to the so-called “Arab Spring”.

Henry Kissinger succinctly summarized the issues raised by this change in his column on the Syrian conflict Friday.

This form of humanitarian intervention distinguishes itself from traditional foreign policy by eschewing appeals to national interest or balance of power — rejected as lacking a moral dimension. It justifies itself not by overcoming a strategic threat but by removing conditions deemed a violation of universal principles of governance.

If adopted as a principle of foreign policy, this form of intervention raises broader questions for American strategy. Does America consider itself obliged to support every popular uprising against any nondemocratic government, including those heretofore considered important in sustaining the international system? Is, for example, Saudi Arabia an ally only until public demonstrations develop on its territory? Are we prepared to concede to other states the right to intervene elsewhere on behalf of coreligionists or ethnic kin?

The US intervention in the Libyan civil war had similar impetus but with far fewer direct actors. In Libya’s case, although dictator Moammar Gadhafi was unseated and killed, democracy is still far from certain. Sectarian divides and mercenary militia forces have created a divide in the country the interim government has yet bring under control as battles and human rights abuses continue. Far worse, the regional consequences of the outflow of weapons and mercenaries from Libya have been devastating, including the fall of the democratic government in Mali and increased intensity of the Syrian conflict.

Syria is a far more complicated proposition. This is a sectarian conflict and the surrounding countries have similar demographics making them vulnerable to inclusion in what is rapidly becoming a larger regional conflict. In Lebanon’s port city of Tripoli, key to weapons shipments for the Syrian rebels, clashes between rebels and locals belonging to Assad’s Alawite sect have claimed 19 lives and created many more wounded. The Lebanese National News Agency reports sustained mortar fire and snipers targeting civilians in the city.

Throughout the region Syrian refugees are taxing the resources of neighboring countries–26,000 in Lebanon, 23,000 in Turkey and more than 110,000 in Jordan. The political stability of Jordan could change quickly with social services and infrastructure being stretched by this newest refugee influx.

The most worrying issue is the makeup of forces inside Syria. Al Qaeda forces have been fighting alongside the rebels in increasing numbers over the past months, escalating the intensity of the conflict. But far worse is the revelation that Iran has Revolutionary Guard troops on the ground. In an interview with Iran’s Insa news agency, Ismail Gha’ani, a top commander in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard said “If the Islamic Republic was not present in Syria, the massacre of people would have happened on a much larger scale, before our presence in Syria, too many people were killed by the opposition but with the physical and non-physical presence of the Islamic Republic, big massacres in Syria were prevented.”

This interview was eventually scrubbed by Insa but the revelation that Iran has troops on the ground in support of the Assad regime, and that they participated in some way in the Houla massacre, signals that Tehran is committed to keeping Syria within its sphere of influence and fundamentally changes the situation on the ground as it pertains to American intervention.

Internationally both China and Russia are providing diplomatic cover for the Assad regime and Russia has been shipping arms to Damascus. This combined assistance along with Iran’s commitment to the conflict makes a protracted conflict regional conflict a near certainty and American or NATO intervention a dubious proposition with little to gain strategically. Mr. Kissinger sums it up perfectly.

Military intervention, humanitarian or strategic, has two prerequisites: First, a consensus on governance after the overthrow of the status quo is critical. If the objective is confined to deposing a specific ruler, a new civil war could follow in the resulting vacuum, as armed groups contest the succession, and outside countries choose different sides. Second, the political objective must be explicit and achievable in a domestically sustainable time period. I doubt that the Syrian issue meets these tests. We cannot afford to be driven from expedient to expedient into undefined military involvement in a conflict taking on an increasingly sectarian character. In reacting to one human tragedy, we must be careful not to facilitate another. In the absence of a clearly articulated strategic concept, a world order that erodes borders and merges international and civil wars can never catch its breath.

Considering the recent American experience with Libya, and with no clear post-Assad objective being articulated by the Obama administration, intervention in Syria beyond diplomacy seems deeply misguided.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.