14 Feburary 2011

Salween River: Burma on the left, Thailand on the right.

Salween River: Burma on the left, Thailand on the right.

The Salween River forms a border between Thailand and Burma. “Rambo” fictionally crossed this jungle current in the movie Rambo IV. But there is nothing fictional about the war, or the bombs that often fly from Burma into Thailand, or the land mines scattered across the hidden countryside.

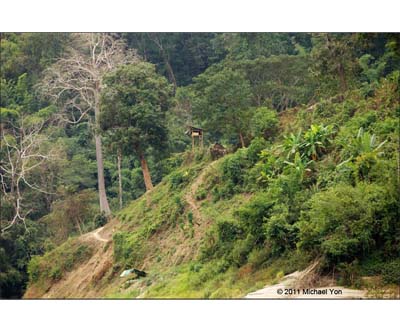

Burmese Army position on Salween River.

Burmese Army position on Salween River.

The Army of Burma is called the “State Peace and Development Council,” or SPDC, and like organizations in Bizarro World, the SPDC is the opposite of what the name implies. A government slogan gets more to the point: “Crush all internal and external destructive elements as the common enemy.”

For more than sixty years, the Burmese government has tried to crush the Karen and other ethnic minorities. In a vague sense, Thailand is to Burma as Pakistan is to Afghanistan; many Karen people live on the Thai side or use it as sanctuary, and fight against the government on the Burma side. But the war is far more complicated than just Karen vs. Burma government; a cursory examination reveals a situation probably more complex than what we see in Afghanistan.

Attempting an ultimate makeover, in 1989, the murderous Burmese government changed the country’s name to the Union of Myanmar. Some months ago, in October 2010, they did it again, changing the flag and forging a new birth certificate with the latest name: “Republic of the Union of Myanmar,” but they might as well have renamed it “The Country Formerly Known as Prince.”

After more than sixty years of war, the Burmese fighting has matured to a point that three generations know only conflict, and instead of Muslim extremists helping Taliban in Pakistan, some Westerners have made a cottage industry of helping Karen and other minorities resist the junta. In total, that cottage industry does good and important work, but it is neither pure nor simple.

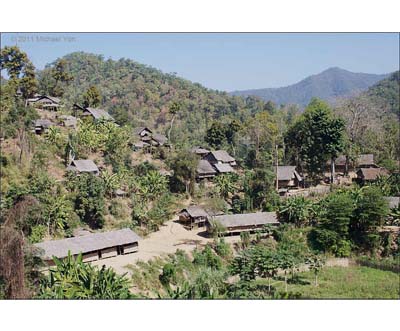

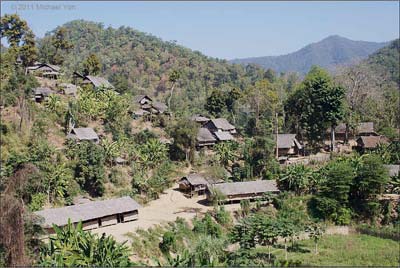

Karen IDP (internally displaced people) village, just inside Burma.

Karen IDP (internally displaced people) village, just inside Burma.

Most Karen people are Buddhists or animists, though many are Baptists or Catholics. This village had at least one Buddhist temple and one thatched church.

The villagers have no telephone service and precious little electricity provided by a small hydro generator, and I saw one tiny solar panel, but someone had a receiver dish (above). This was the only dish I saw in a village of about 4,500 people. (There may have been other dishes; we were not taking inventory.)

The people have been here for about 4.5 years since the SPDC destroyed their villages. One hears many stories about murder, rape, slavery, and countless land mine reports, such as how the SPDC will force villagers to walk out front to detonate mines. The Karen do fight back and are increasing the use of IEDs, for instance, which have taken on an evil name, though as American soldiers we learned to make all sorts of IEDs in the US Army, which we called “mechanical ambushes,” or just booby traps.

The day before we arrived, a Karen man stepped on a land mine and was brought to this village before being sent to Thailand for treatment. A Karen medic who applied the tourniquet said the man lost the lower part of a leg. The nearest hospital requires about an hour by boat and then an hour by car to Mae Sariang, Thailand.

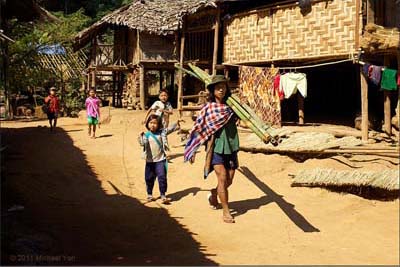

The Karen villagers were friendly and happy to have their photos made.

The Karen villagers were friendly and happy to have their photos made.

The children were polite and never begged.

Deep in the jungle, no sounds of motors or phones.

Deep in the jungle, no sounds of motors or phones.

The cosmetic on their faces is called “thanaka” which they say is good for pimples, prevents sunburn and makes a cooling sensation on the skin. Thanaka, derived from the bark of several types of trees, is also used simply as makeup.

Nearly all the kids were in school or a nursery.

Nearly all the kids were in school or a nursery.

They met us with a mixture of smiles, waves and curiosity.

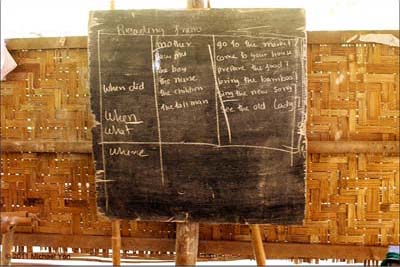

The man with the red and white shirt (above) is a village medic who treated yesterday’s land mine victim. His English is good. Inside his hut, English words were written on a blackboard because, he said, he continues to learn.

A few of the kids were not in the classes but were working. The medic said most kids go to school, but attendance is the parents’ choice, and some parents just keep their kids in the fields.

This boy had an RPB, or Rocket Propelled Banana. While most of the kids his age were in classes just a few minutes’ away, this boy apparently was being left behind.

They had pigs, chickens, bananas, and many types of foods. There was a fish pen by a creek, and the Salween River, though much of their food is donated and comes through Thailand. A coconut husk lay on the ground but there were no coconut trees; the medic said the coconuts come via Thailand.

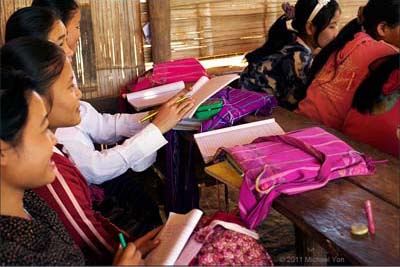

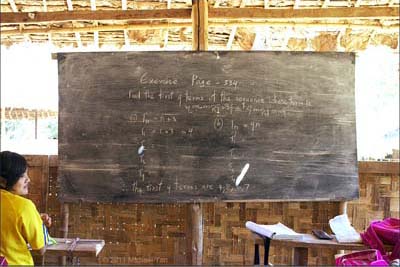

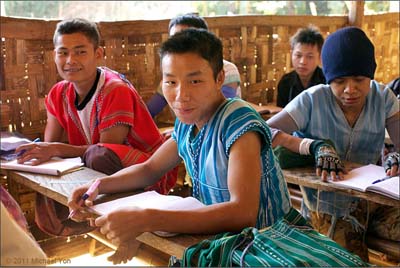

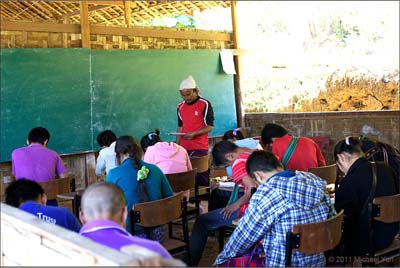

Girls and boys attended the same classes while

Girls and boys attended the same classes while

sitting on opposite sides of the aisles.

There must have been a couple dozen classrooms of this approximate size.

There must have been a couple dozen classrooms of this approximate size.

Wilbur the pig walked into this class.

Wilbur the pig walked into this class.

The kids ignored the pig but were curious about us.

Expensive classrooms are not important.

Expensive classrooms are not important.

Just good teachers, industrious students, and some quality books.

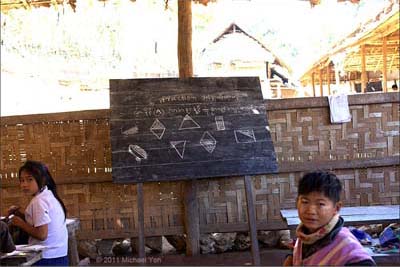

In addition to math, history and other topics, the kids were learning Karen,

In addition to math, history and other topics, the kids were learning Karen,

Burmese, Thai, and English. I walked into an English class and taught

for a couple minutes. The kids could read and were eager to speak English.

Don’t be surprised if you stumble into a remote village and

Don’t be surprised if you stumble into a remote village and

find kids who are better at math than you are!

Living in this jungle world are a people without a country. Other ethnic minorities in Burma face similar pressures, though after decades of fighting, the minorities have been unable to forge a strong united front.

The minorities have limited freedom of movement. It’s hard to know if the jungle is a prison, freedom, or both. If prison is lack of freedom, and freedom is lack of prison, both are as much a state of mind as of matter.

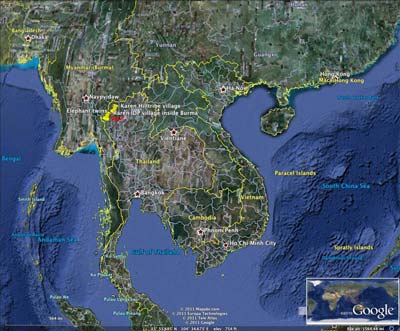

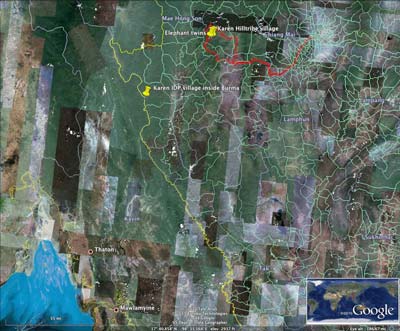

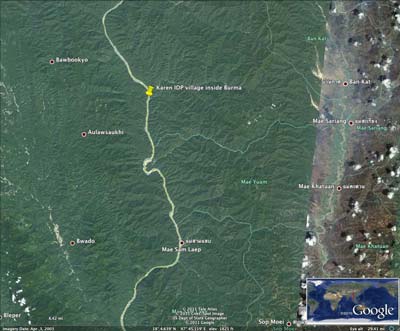

The yellow pin to the left is just inside Burma at the Karen IDP camp we visited.

The yellow pin to the left is just inside Burma at the Karen IDP camp we visited.

Yellow trace is the Thai-Burma border, with Thailand on the right.

Yellow trace is the Thai-Burma border, with Thailand on the right.

The pin on the right is the location of the Jungle Twins described in a recent dispatch.

Rugged jungle: Prison, freedom, or both?

Rugged jungle: Prison, freedom, or both?

The red trace describes the GPS track we walked through the

The red trace describes the GPS track we walked through the

‘Ei Htu Hta’ IDP camp while creating these images. Thailand is this side of the river.

There are many stories about Ei Htu Hta on the Web; the trip to Ei Htu Hta makes for a journalistic smash and grab; limited commitment is required to get in and out, the danger is trivial for the journalist, and so “reading caution” is in order. One hears of stories of journalists crossing the river only to do a quick stand-up, “Here we are in Burma,” and crossing back to Thailand. This has been common in Iraq and Afghanistan. The drama is dramatically meaningless.

The conditions in Ei Htu Hta are not good, but conditions appeared far better than I see in countless other places in many countries that are not at war. In fact, the people Ei Htu Hta probably live better than dozens of millions of Indians. I believe what this says is that private and international aid is having a positive impact here, but to keep aid flowing, some people think a glum face is needed. But why? The truth of these smiling kids in school can be taken as evidence that help is working.

A paradox, as within Afghanistan today, is that places at war, such as Helmand and Kandahar, sometimes get billions of dollars while other places in Afghanistan, such as Bamiyan, where little action occurs, get mostly forgotten. This is not to suggest a change in course, but only to shine a penlight for others to know.

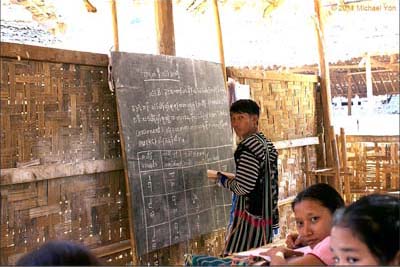

Another teacher explained that this is a leadership course.

Another teacher explained that this is a leadership course.

We had lunch with a couple of Karen medics; one had caught a rabbit with a trap in the jungle and roasted it.

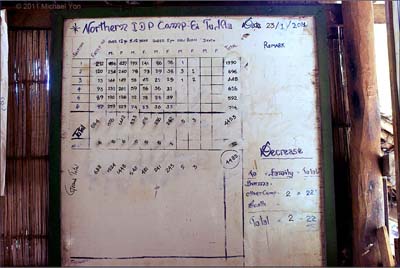

Camp population listed at 4,482.

Camp population listed at 4,482.

Life without lawyers or road signs. They have no police. No courts. I asked detailed questions about their justice system. If someone is accused of a serious crime, the accused is sent to the Karen army who decides the outcome. For petty transgressions around the village, the perpetrator is tied up for one night. According to the brief explanation, villagers bind his ankles together but not his hands, and release him the next day. Sounded more like a humiliation, which also can occur in places like Afghanistan, though humiliation there can take the form of sodomy by man or implement.

“What would be a typical crime?” I asked. Sometimes a man gets drunk and burns down his own house. “Burns down his own house on purpose?” I asked. “Yes, sometimes a man burns down his own house.” “What do you do when there is fire?” I asked. “We build houses apart from each other.”

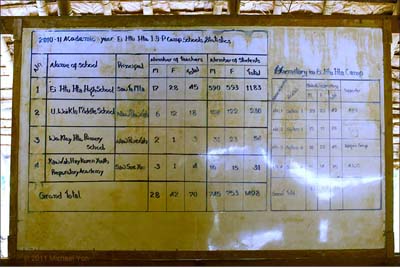

School attendance listed at 1,498 students.

School attendance listed at 1,498 students.

These boys followed us around. Never begged but they smiled a lot.

These boys followed us around. Never begged but they smiled a lot.

During this photo, we were in a church and they were sitting on bamboo pews.

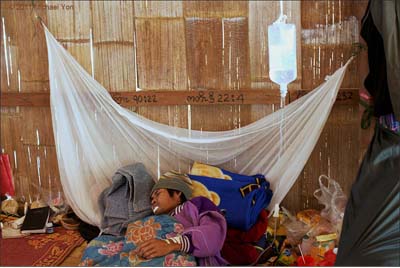

This jungle has it all: from malaria to cobras to land mines, but no doctors and little medicine. The British military would call this a “dirty jungle” as opposed to the “clean jungle” down in Borneo. Dirty jungles have more parasites, diseases, and other hazards that put down a lot of troops and inhabitants.

Mom said her baby had a fever.

Mom said her baby had a fever.

And then it was time to go. We walked back to the boat for the return trip.

The SPDC uses the river for transport where they face ambush, and so they travel as civilians. A Karen man said Karen soldiers had ambushed SPDC in a boat upriver some days before, and that about six SPDC were killed and wounded. He said the Karen intercepted SPDC radio chatter indicating six casualties.

Chugging downriver back to the Thailand exit, we found a corpse caught by a fishnet in the Salween River (above). Maybe the body belonged to an SPDC soldier and had floated down from the reported ambush. We could only imagine the surprise of a fisherman if he shows up with a light tonight. I took coordinates for Thai authorities.

In closing, my experience in Burma is eggshell thin. Many people have spent years with resistance organizations or providing help, or perhaps simply smuggling or running some sort of nefarious enterprise. Some are missionaries, others mercenaries, and, as the saying goes, others are misfits.

The mature business surrounding the conflict is complex and not always altruistic. There also is a continuum of “band aide for the buck”: some organizations will accomplish much, while others will do little and spend much time making videos to raise money.

Before deciding to help any causes here, or anywhere, due diligence is the first order. For every bullet there is a lie, and one must beware of crocodile tears.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.