SYDNEY (AP) — Australia’s top cyberwarrior revealed Wednesday that his country actively participated in the electronic war against the Islamic State group in Syria, degrading their communications during military operations and actively stopping people seeking to join the extremist group.

The director-general of the government-run Australian Signals Directorate, Mike Burgess, spoke publicly for the first time about his agency’s work.

Burgess cited an example of how the cyberwarfare body helped the Australian Defense Force and its allies win a critical battle with IS.

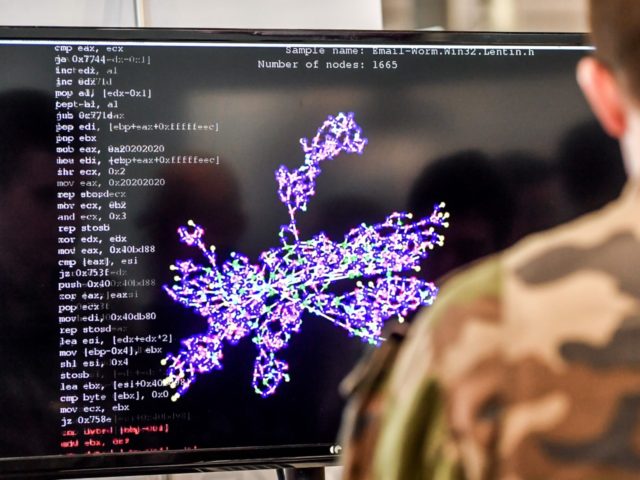

“Just as the coalition forces were preparing to attack the terrorists’ position, our offensive cyberoperators were at their keyboards in Australia — firing highly targeted bits and bytes into cyberspace,” Burgess said in a speech at the Lowy Institute, an Australian strategic think tank.

He said IS communications “were degraded within seconds.”

“Terrorist commanders couldn’t connect to the internet and were unable to communicate with each other. The terrorists were in disarray and driven from their position — in part because of the young men and women at their keyboards some 11,000 kilometers (6,900 miles) or so from the battle.”

Burgess said the operation required weeks of planning by his agency and military personnel and was unprecedented in terms of how cyberwarfare was closely synchronized with the movements of military personnel.

“And it was highly successful. Without reliable communications, the enemy had no means to organize themselves. And the coalition forces regained the territory,” Burgess said.

He said his agency had also inflicted important damage to IS’s “media machine” by locking it out of its servers and destroying propaganda material, undermining its ability to “spread hate and recruit new members.”

In a rare departure — anywhere in the world — from the secrecy that typically surrounds such operations, Burgess painted a fuller picture of his agency’s work in a speech aimed at recruiting more operatives.

“Our targets may find their communications don’t work at a critical moment — rather than being destroyed completely. Or they don’t work in the way they are expecting. Or they might find themselves not able to access their information or accounts precisely when they need to,” he said.

Operatives came from all walks of life, having studied anything from mathematics to biology and marketing, he said. They sat at computers in Canberra, where they worked against IS on battlefields in Syria.

He said another operation began after his agency learned of a man “in a remote location” who had been radicalized and was attempting to join a terrorist group. A team was assembled, including linguistic, cultural and behavioral experts, which was headed by a young female science graduate in Canberra who was pretending to be a senior male terrorist in the Middle East.

“ASD tracked down and reached out to the man over the internet. Pretending to be a terrorist commander, our lead operator used a series of online conversations to gradually win her target’s trust,” Burgess said.

“To ensure he couldn’t be contacted by the real terrorists, she got him to change his modes and methods of communication. Eventually, she convinced the aspiring terrorist to abandon his plan for jihad and move to another country where our partner agencies could ensure he was no longer a danger to others or himself,” he said.

Burgess said the woman who led the operation was like many “from fairly ordinary backgrounds” who worked to help Australian operations abroad, or to prevent cyberattacks targeted at Australia.

“And when she was studying science at university, she would never have dreamed that one day she would be posing online as a terrorist and helping to defend Australia from global threats,” he said.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.