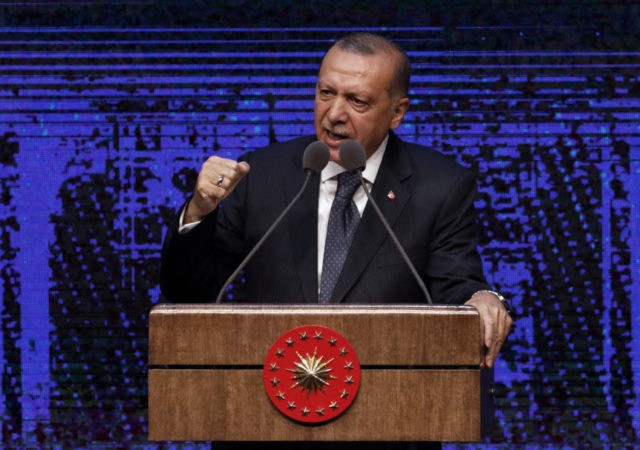

Can Dündar, the former editor-in-chief of Turkey’s last remaining opposition newspaper Cumhuriyet, condemned Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan for claiming to defend the free press in the aftermath of the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.

Dündar, also writing in the Washington Post from exile in Germany, notes, “the difference between me and Jamal Khashoggi is that his assailants were better prepared and didn’t miss their target” in a piece whose title calls Erdogan the “world’s biggest hypocrite” for defending Khashoggi. Khashoggi, a longtime Islamist sympathizer and critic of reforms in Saudi Arabia under Crown Prince Muhammad Bin Salman, disappeared in October after entering the Saudi embassy in Istanbul. Riyadh ultimately admitted that Saudi officials killed him, but have refused to blame any individual for the plan or hand over Khashoggi’s body.

“Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has played up the despicable killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi to his own considerable advantage,” Dündar writes, noting that Erdogan has regularly pressured the Saudi government to disclose the details of Khashoggi’s death. “From his relentless pursuit of Khashoggi’s murderers, you’d almost think he has genuine concern for freedom of the press. Don’t believe a word of it.”

The Turkish journalist retells the story of how he ended up in Germany, separated from his wife for two and a half years because Erdogan’s government will not let her leave Turkey but put out an arrest warrant for Dündar to be apprehended the second he returns to his home country.

In Germany, Dündar has launched another publication, titled Ozguruz, to report freely on Turkish news.

Dündar’s newspaper Cumhuriyet skews secularist and has for years criticized Erdogan’s government as increasingly dictatorial, Islamist, and paranoid, arresting tens of thousands for alleged ties to everyone from arch-rival Fethullah Gülen, an Islamic cleric exiled in Pennsylvania, to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated Marxist terrorist organization.

Dündar, along with Cumhuriyet‘s Ankara bureau chief Erdem Gül, were arrested in 2015 for publishing a report detailing evidence that Erdogan’s intelligence service, the MIT, was illicitly shipping weapons into Syria for use by rebels who oppose dictator Bashar al-Assad. At the time, Erdogan had not yet declared that Turkey would “end the rule of the tyrant Assad,” nor had the July 15, 2016, failed coup occurred against his regime, which triggered tens of thousands of arrests and the shutdown of as many as 180 media outlets. The report had an explosive impact on the diplomacy surrounding the Syrian civil war at the time.

Dündar writes that he met Erdogan on two occasions personally before his arrest and that, on one occasion, “I protested on his behalf when, in 1997, he was sentenced to prison for reading a poem with religious motifs, out of my belief in freedom of expression.” Dündar notes that Erdogan had “been an active Islamist since his university days,” placing him “on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum.”

Any sympathy Dündar had earned from that protest had rapidly dissipated by 2015.

“I had produced a documentary about how this man who spent his youth in poverty had gotten rich in power. Additionally, I had published footage showing the Turkish intelligence service illegally delivering weapons to Islamist groups in Syria,” he wrote in the Post. “Erdogan was unable to refute the revelation, but the next day he appeared on TV, declaring, ‘The person who reported this is going to pay a heavy price.'”

“I paid by standing trial, facing two life sentences, serving three months in jail and enduring an attack by a gunman on the day of the court’s decision,” Dündar writes.

In May 2016, after stepping outside of a courthouse following a recess in proceedings over the Cumhuriyet Syria report, a man identified as Murat Şahin ran towards Dündar shouting “traitor!” and shooting at him. He missed and the government dropped charges against him for attempted murder. As Dündar notes in his Washington Post piece, “my would-be assassin was released without punishment, while my wife, who jumped on the assailant to protect me, has been banned from leaving the country, so that we’ve been separated from each other for the past two and a half years.”

Dündar still faces prison time if he returns to Turkey. In October, shortly after Khashoggi’s disappearance, an Istanbul court issued yet another warrant, this one an “international red notice,” for Dündar on “espionage” charges for publishing the 2015 Syria report.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) published its annual global freedom of the press report on Thursday declaring Turkey the most prolific jailer of journalists in the world for the third year in a row. Of the 251 journalists known to be in prison currently, 68 are in Turkey, and all facing charges for speaking out against the government.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.