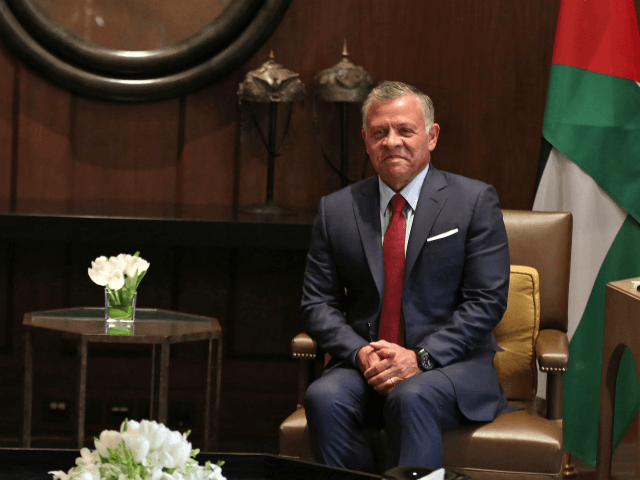

It is an open secret, seldom discussed, that the regime of King Abdullah II of Jordan is extraordinarily weak.

He is viewed in the U.S. as a close ally, whose counsel is sought by senior officials and foreign policy practitioners. But more than an ally, Abdullah is a dependent. Without the U.S. — and to a similar degree, without Israel — the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan would not long survive.

The weakness of the Kingdom has two sources. First, Jordan is poor. It lacks natural resources, and due to the regime’s failure to liberalize the economy or reform the legal system in order to cultivate economic growth and productivity, there are few opportunities for private advancement. The average Jordanian lives in poverty. Per capita income in Jordan is $3,238 per year.

The second source of the Kingdom’s weakness is the unpopularity of the regime. The Hashemites are Beduins. They were installed as monarchs of the area by the British in the aftermath of World War I. The vast majority of the population is Palestinian, not Beduin. The Palestinian majority in Jordan is systematically discriminated against by the regime. That regime-based discrimination has escalated steeply in recent years. Palestinians have been ejected from the military and denied the right to work in various professions.

The Hashemite regime is based on an alliance it built with the other Beduin tribes east of the Jordan River. But the bonds between the Hashemites and the other Beduin tribes have been steadily eroding. Over the past year, the Beduin have been leading mass, countrywide protests against the regime. They demand the transformation of the monarchy from an effective dictatorship, where Abdullah controls all aspects of the government, into a constitutional monarchy along the lines of the British monarchy. Several of the tribes are allied with Islamist groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood and al-Qaeda.

The weakness of the Kingdom of Jordan is the cause of King Abdullah’s abrupt announcement on Sunday that Jordan is canceling two annexes of the 1994 peace treaty it signed with Israel. The annexes in question set the terms for Israel’s 25-year lease of lands along the border with Jordan, at the Tzofar enclave in the Arava desert in Israel’s south, and at the so-called Isle of Peace at Naharayim, adjacent to the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel.

Sovereignty over the lands was long disputed, although Israeli farmers had cultivated the areas since the 1920s. In a goodwill gesture to his partner in peace, Abdullah’s father, the late King Hussein, then-Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin agreed to cede Israel’s claims to sovereignty in exchange for the long-term lease.

Abdullah’s move was not a breach of the letter of the agreement, although it marks a significant downgrade of the peace. The treaty allows for one party to announce its intention not to extend the terms of the lease and then enter consultations relating to the move with the other side.

But as Israeli scholar and Jordan area specialist Eyal Zisser explained in Yisrael Hayom on Tuesday, in making the announcement, Abdullah signaled that he is “disavowing the spirit of the 1994 peace agreement and turning [his back] on the partnership forged between Rabin and Hussein.”

The timing of the announcement reinforced this assessment. Abdullah added insult to injury by announcing he was abrogating the lease deals on the Hebrew anniversary of Rabin’s 1995 assassination.

As Zisser recalled, Rabin was far more enthusiastic about the peace deal with Jordan than he was about the peace process with the PLO. He believed that Israel could rely on the Hashemite dynasty to keep its part of the bargain.

Rabin was correct that Israel could rely on the monarchy. Even before Israel and Jordan signed the formal peace deal, the Hashemite regime was Israel’s strategic partner – and dependent.

Israel’s problem was never with the regime, which rightly views Israel as the guarantor of its survival, both militarily and in term of natural resources. Israel provides Jordan with most of its water and is set to begin exporting natural gas to Jordan in 2020.

The bar to peace between the neighboring states has always the people of Jordan. According to Pew’s 2014 survey of global opinion,100 percent of Jordanians have negative views of Jews. Also according to Pew survey data, Jordan is second only to Egypt in hatred for America.

Abdullah’s decision to cancel the annexes was without a doubt an attempt to win public approval.

Israel’s response to the announcement was mixed. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu tried to neutralize the issue by saying Israel and Jordan would enter into negotiations in a bid to restore the lease agreement, in accordance with the treaty. But Jordan quickly nixed the idea. Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi responded that Abdullah’s decision is final.

Senior Israeli government ministers, speaking anonymously, told reporters that Israel must retaliate against Abdullah by ending its plan to increase its water transfers to Jordan. Expanded humanitarian aid to Jordan, under the circumstances is “an absurd gesture,” they said.

Israel’s quandary, however, like the U.S.’s dilemma, is that Abdullah is the most dependable leader they can expect from Jordan for the foreseeable future. Unfortunately, as far as Israel is concerned, there is no popular constituency in Jordan for peace.

Indeed, hostility for Israel is so high that despite Jordan’s water shortage and need for natural gas to power its sclerotic economy, according to Israeli businessmen who travel frequently to Jordan, large protests take place regularly demanding that the regime abrogate its water and gas deals with Israel.

With Iran perched on Jordan’s doorstep in Syria, it is fairly clear that it would be unwise for Israel or the U.S. to make any moves to further destabilize the regime. Indeed, both would be wise to help strengthen the regime. But while doing so, it is imperative as well for the U.S. and Israel to use their leverage against the regime to force it to begin lowering the flame of antisemitic and anti-American rhetoric.

As far as Jew hatred is concerned, the State Department’s 2017 report on International Religious Freedom noted, far from working to moderate Jew-hatred in the kingdom, state-controlled media in Jordan promote Jew-hatred.

According to the report, “Editorial cartoons, articles, and postings on social media continued to present negative images of Jews and to conflate anti-Israel sentiment with anti-Semitic sentiment. The government continued not to take action with regard to anti-Semitic material appearing in the media, despite laws that prohibit such material.”

Attitudinal changes tend to be a generational undertaking. Abdullah has now been monarch in Jordan for nearly a generation. His weakness, and his dependency on the U.S. and Israel, should spur both governments to continue to support him on the one hand, and to demand that he take action in the media, in the school system, and his government-controlled mosques to moderate sentiments and cultivate tolerance among his subjects on the other.

Otherwise, no matter how much support Abdullah receives, at some point the Kingdom of Jordan will be overturned, and it will take vital Israeli and U.S. strategic interests with it.

Caroline Glick is a world-renowned journalist and commentator on the Middle East and U.S. foreign policy, and the author of The Israeli Solution: A One-State Plan for Peace in the Middle East. Read more at www.CarolineGlick.com.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.