About two dozen residents of the coastal Southern California city of Oceanside protested outside City Hall on Wednesday afternoon to oppose an effort to impose what they call a racist voting system on their city.

The group, calling itself the Oceanside Citizens Coalition, included local residents as well as representatives of the Oceanside Republican Women Federated, the Tri-city Tea Party, the Ocean Hills Republican Club, San Diegans for Secure Borders, and the San Diego Patriots.

The Oceanside city council is considering a proposal to divide the city into separate voting districts, which would each elect one member to the council. One or more districts would be created specifically to produce minority council members.

Currently, the city council’s five members are elected on an at-large basis, where each is accountable to the electorate as a whole. The at-large system is common in small communities throughout the state.

The change is being prompted by a March 22 letter from Malibu, California-based attorney Kevin Shenkman, who alleged that the city’s current at-large council system violates the California Voting Rights Act (CVRA) of 2001.

In the letter, Shenkman claimed that the at-large system discriminates against racial minorities, because the racial majority can vote in a bloc to exclude minorities from office.

He asserted that “voting within Oceanside is racially polarized, resulting in minority vote dilution,” though he did not provide any evidence, other than the fact that one Latino candidate, Linda Gonzales, recently lost an election to city council. He claimed that she lost because of “bloc voting of Oceanside’s majority non-Latino electorate.”

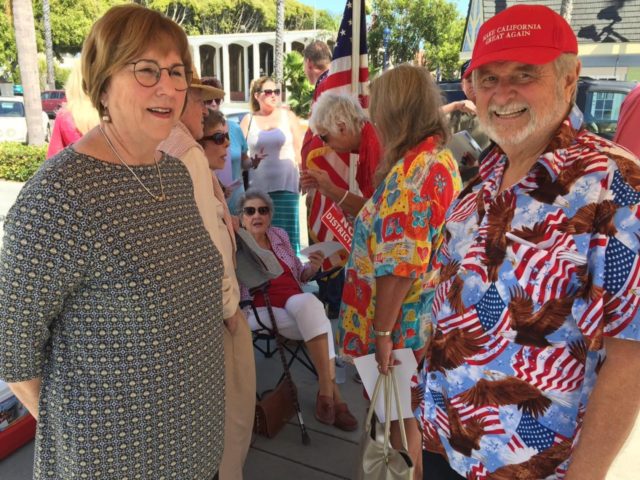

Linda Gonzales herself (above left) disagrees.

“I lost because I was running against two incumbents who had been on the council 16 years,” not because of racism, she told Breitbart News at the protest.

Gonzales, who has lived in Oceanside for 50 years, joined the demonstrators to oppose the new districting system. She was also irritated that Shenkman used her name in his letter to the city.

“I called them immediately, and told them I don’t believe in identity politics,” she recalled.

“They just kept talking. It wasn’t about me. [Shenkman] just used my name, and he used me.”

According to the U.S. Census, Oceanside is 65.2% white, 35.9% Latino, and 4.7% black. One of the city’s current five council members, Esther Sanchez, is Latina.

In a press statement, the Oceanside Citizens Coalition noted that the local community had elected several Latino leaders without discrimination or interference.

“[O]ur fair and equitable at-large voting system … has given us such fine [minority] city representatives as Assemblyman Rocky Chavez, 5-term current councilmember Esther Sanchez, Mayor Terry Johnson, and Luci Chavez, who have all been elected to high city positions over the past 25 years,” spokesperson Patti Siegmann said.

The lawyer from Malibu

Resident Mike Richardson, who was born in Oceanside, said of Sheknman’s effort: “It’s a fraud. It’s such a welcoming, inclusive, friendly city. There is no racial division here.

“It is a total lie. They don’t know us, they don’t care about us. They just have an agenda of their own,” he told Breitbart News.

Richardson said that a district system was more appropriate for a big city. “We know how to govern ourselves.”

Shenkman’s law firm, Shenkman & Hughes, reportedly represents the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project (SVREP), an organization that is based in Texas and has an office in Los Angeles.

SVREP’s mission, according to its website, is “to empower Latinos and other minorities by increasing their participation in the American democratic process.” It was founded by Mexican-American activist Willie Velasquez in the 1970s.

Shenkman’s firm is based in Malibu, California, an elite coastal enclave that is 91.5% white and is popularly known as a playground for Hollywood stars.

Malibu has an at-large city council — the same system Shenkman sues other cities to destroy — of five members, all of whom are white, as of the current term.

Shenkman failed to respond to an inquiry as to whether he plans to sue Malibu.

In 2009, the Associated Press reported that lawyers were making a fortune by suing cities and school boards under the CVRA, and forcing them into costly settlements.

Moreover, the AP said, “all of the roughly $4.3 million from settlements so far can be traced to just two people” — namely, the attorneys who wrote the legislation, Joaquin Avila and Robert Rubin.

The AP also noted that local officials who had been sued considered the law a “money grab,” adding that they had never heard complaints about racial discrimination in their communities before being sued.

The AP added:

There is nothing illegal about the lawyers profiting from a law they authored and state lawmakers approved. But it is unusual that after seven years all legal efforts are so narrowly focused, especially since Avila told lawmakers when he testified for the bill in 2002 that he expected other attorneys would take on cases because of favorable incentives written into the measure.

That moment has apparently arrived, with Shenkman pressuring dozens of jurisdictions in Southern California, reaching quick settlements in some cases, and winning in court in others.

In his letter to Oceanside, Shenkman warned the city not to try its luck in court:

As you may be aware, in 2012, we sued the City of Palmdale for violating the CVRA. After an eight-day trial, we prevailed. After spending millions of dollars, a district-based remedy was ultimately imposed on the Palmdale city council, with districts that combine all incumbents into one of the four districts.

Shenkman issued a May 5 deadline for the city to respond before his clients were “forced to seek judicial relief.”

Protesters expected the Oceanside city council to capitulate, but were holding out hope.

‘Organized crime through law’

There are reasons to believe the CVRA may be unconstitutional.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shaw v. Reno (1993) that so-called “majority-minority” districts, designed to increase the chance of electing minorities, could be invalidated if the “rationally cannot be understood as anything other than an effort to separate voters into different districts on the basis of race.”

Since then, further cases have refined the Supreme Court’s standards for creating voting districts. While the government may have a “compelling” interest in redressing past discrimination, which could justify the creation of majority-minority districts, that would not justify every such scheme, the Court has found.

On the other hand, in 1986, the Supreme Court held in Thornburg v. Gingles that the mere fact that minorities had been elected in the past would not be enough to disprove a violation of the federal Voting Rights Act by “dilution.” It established a three-prong test for demonstrating a dilution of minority votes:

First, the minority group must be able to demonstrate that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district. …

Second, the minority group must be able to show that it is politically cohesive. …

Third, the minority must be able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it — in the absence of special circumstances, such as the minority candidate running unopposed … usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.

The CVRA is far more aggressive, removing the first of the requirements above, and adding: “Proof of an intent on the part of the voters or elected officials to discriminate against a protected class is not required.”

Effectively, under the CVRA, if a minority group votes as a political bloc, it can demand an end to at-large elections, and the creation of a dedicated district for its own members.

When the Central Valley city of Modesto, California went to court to defend its at-large system over a decade ago, the trial court declared the CVRA unconstitutional.

But a state appeals court overturned that ruling in 2006, holding in a decision known as Sanchez v. City of Modesto that the CVRA itself did not discriminate on the basis of race.

“Just as non-Whites in majority-White cities may have a cause of action under the CVRA, so may Whites in majority-non-White cities. Both demographic situations exist in California, even within our own San Joaquin Valley, and the CVRA applies to each in exactly the same way,” the court found.

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case, or to tackle the question of whether the CVRA’s provisions are unconstitutional, leaving the appellate court’s decision in place ever since.

Not even liberal enclaves are safe from Shenkman and SVREP.

Santa Monica — known affectionately by locals as the “People’s Republic” — was sued by Shenkman last year. Left-wing city council members were at pains to explain that there are many minorities on local elected bodies, and that the local electorate does not discriminate. At the time Shenkman sued the city, it had a Latino mayor, Tony Vazquez.

But few cities have been prepared to go to court after the decision in Sanchez v. City of Modesto.

Amy Sutton, who joined Wednesday’s protest from nearby San Marcos, California, said she did not want to see Oceanside go the way of her city, which capitulated to threats by Shenkman last year.

“They folded right away … I actually didn’t know anything about it until after it happened. Then I started researching it.”

She noted that similar activists are targeting cities and school districts all across Southern California.

“It’s judicial racism and it’s unconstitutional. There’s no way any city can win this because of organized crime through law.”

New legal hope?

There are reasons to believe that a new legal effort might succeed under recent Supreme Court rulings — and with Justice Neil Gorsuch on the bench.

In 2013, in Shelby County v. Holder, the U.S. Supreme Court declared Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional. The law had required a group of states, mostly in the South, to obtain “preclearance” from the federal government before making any changes to their voting systems. The Court found that those states had seen enough improvement since the Civil Rights era to make the list of states obsolete. Absent convincing evidence of ongoing discrimination, the Court said, holding those particular states to a separate standard was unconstitutional.

That might improve the chances of a constitutional challenge to the CVRA by a city like Oceanside, on the grounds that it does not demand enough evidence of discrimination before declaring at-large voting systems void.

The Oceanside Citizens Coalition argues that the rights being diluted are those of the electorate as a whole: “District voting in smaller cities like Oceanside is … a violation of the Federal Voting Rights Act,” Siegmann said in her statement, “because it disenfranchises and dilutes voters’ votes by 75% in choosing their city councils, by reducing their voting power to one district councilmember instead of four.”

Hans van Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at the Heritage Foundation, called the California statute “problematic.”

“The California statute seems to be racist, in that it assumes that your opinions, and whom you vote for, depend on your skin color,” he told Breitbart News.

“In these communities, on local government bodies, you want elected officials whose interests reflect the entire community, not just the interests of one small district, or one small section of a city.”

Gonzales agrees. She told Breitbart News she believes that a district system is bad for local governance because it means council members will be less responsive to residents.

She added: “I told [Shenkman] that I agree we need to get more Latinos involved in the government, and in our democracy, and in our Constitution. He didn’t want to talk to me after that.”

“They’re working against the people they’re trying to help,” she concluded.

Breitbart News contacted city council members to elicit their views on the proposal. None returned calls for comment.

Update: The city council approved a plan to begin developing a district system by a vote of 3 to 2, after a presentation in which the city attorney advised the council that no city in the state had ever prevailed against a challenge in a CVRA case. Roughly 40 people stood up to speak, the overwhelming majority against the proposal.

Councilmember Esther Sanchez spoke in favor, arguing that it would be more “democratic”; Councilmember Jack Feller was opposed; and Councilmember Jerome Kern said that he did not like the proposal but could not risk the financial cost of fighting it.

Mayor Jim Wood, after decrying the way the proposal had been forced on the city, voted against it. It was not enough.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News. He was named one of the “most influential” people in news media in 2016. He is the co-author of How Trump Won: The Inside Story of a Revolution, is available from Regnery. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

Correction: An earlier version of this post had indicated, in error, that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act had been declared unconstitutional, when in fact it was Section 4.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.