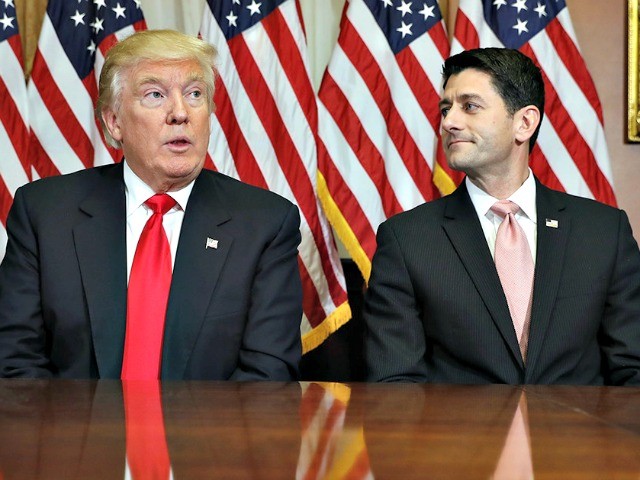

The Wall Street Journal recently reported President-elect Donald Trump stating that he may oppose the border adjustment tax provisions of the House Republicans’ corporate tax reform as “too complicated.”

Speaker of the House Paul Ryan was left almost speechless when Trump told the Journal: “Anytime I hear border adjustment, I don’t love it.”

The border adjustment measure is the linchpin of Ryan’s “Better Way” tax reform blueprint, which was discussed with Trump’s transition team during a January 16 meeting on Capitol Hill.

Although Trump’s trade economist Peter Navarro supports the concept of a “border adjustment tax” to boost U.S. domestic manufacturing by taxing imports to offset America’s sky-high 35 percent U.S. corporate tax rate, the President-elect warned the measure could be “adjusted into a bad deal.”

Speaker Ryan proposes to eliminate the corporate income tax and replace it with a “destination-based cash-flow tax” (DBCFT) to make the U.S. an attractive location for international investor. The DBCFT is basically value-added tax (VAT), like every other advanced nation currently employs. But the big difference in the “Better Way” is that U.S. companies still be able to deduct the cost of labor costs, like the current corporate tax.

U.S. companies are subject to a maximum 35 percent worldwide corporate income tax rate. That compares to a top corporate tax rate of 18.6 percent in Europe and a 15 percent in China, which serves as a strong incentive for companies to locate production outside if the U.S.

Some tax experts claim that the foreign corporate tax rate advantage is offset by the 21 percent VAT in Europe and 17 percent VAT in China. But the U.S. companies complain that they are disadvantaged, because foreign nations exempt VAT on their exports and charge VAT on imported U.S. products.

As a modified VAT, Ryan claims that the DBCFT would also encourage more equity investing by eliminating the U.S. corporate tax’s incentives for highly leveraged debt investing, due to the tax destructibility of interest payments. Reducing debt might be a virtue to Ryan, but this changes would hurt highly leveraged real estate and commodity speculators.

The DBCFT could be controversial, because it slashes the corporate tax rate from 35 percent down to as low as 20 percent; while leaving the top personal income tax rate at 39.6 percent.

The Brooking Institute warns that another negative political “optic” of the DBCFT is that U.S. exporters, like Harley Davidson (headquartered in Ryan’s congressional district), could have a “negative net tax liability.” That means profitable U.S. exporters could receive huge refund checks from the Treasury.

Ryan’s tax changes would act as an indirect tax on consumers, by immediately raising the cost of most imports. Ryan claims this would stimulate re-shoring of factories back to the U.S., but that could take time and might never happen.

A potential wildcard from the “Better Way” is the possibility of driving up the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar by 20 percent. The strong dollar would be devastate many emerging market economies, like Mexico, Brazil and Turkey that have heavily borrowed in U.S. dollars. It could also slash U.S. tourism.

Some tax lawyers point out that DBCFT could violate World Trade Organization rules that allow certain border tax adjustments for VATs, but do not allow the destructibility for wages.

Given that his “Make America Great Again” initiatives have already caused the biggest jump in the National Federation of Independent Business’ confidence index since the Reagan Administration 30 years ago, President-elect Trump may be concerned that trying to explain the complicated math of the “destination-based cash-flow tax” might undermine his strong momentum.