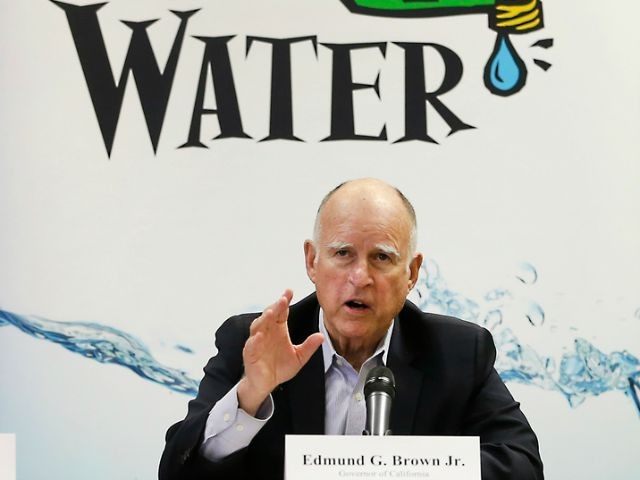

For years, California Gov. Jerry Brown has advocated for a pair of pricey tunnels that would divert water from the Sacramento River south to boost state supplies–and some observers say that 2016 is shaping up to be the year of reckoning for the project.

In a column likening Brown to a salmon swimming upstream, the Sacramento Bee‘s Dan Morain details the delicate balance the governor will have to strike if he is to seal the deal on the $15.5 billion tunnels and ensure the beginning of their construction.

“Given all the obstacles, Brown will need to do much more than offer derisive or dismissive comments,” Morain writes. “He’ll need to sell Californians on the need for the project. Either that or come up with a Plan B, which would not surprise me.”

Like any political battle, Brown must contend with two warring sides. On one side sit pro-business and farm groups, including organizations like Californians for Water Security, who want to see the tunnels built to ensure an adequate supply of water for the southern portion of the state. The pro-tunnel lobby, which includes the California Chamber of Commerce, has reportedly spent “well into the six figures” on advertising designed to sway public opinion. The Metropolitan Water District, supplier to 19 million Californians as the state’s largest water agency, also backs the tunnels.

On the other side are environmental groups like Restore the Delta, which argue that the tunnels’ construction would harm the ecology of the Sacramento River and turn the Bay Delta area into an industrial wasteland.

Complicating matters further for Brown, the roughly eight-year-old tunnel plan could still be derailed or delayed by mandatory California Environmental Quality impact reports, an uncooperative Environmental Protection Agency, and difficulty acquiring land from Delta farmers to ensure the necessary space for the tunnels.

There’s also the matter of an upcoming ballot measure that could limit the state’s ability to fund the project. The Public Vote on Bonds Initiative, sponsored by wealthy Stockton-area farmer Dean Cortopassi, would require any infrastructure bonds exceeding $2 billion be subject to the approval of voters. Brown’s office has publicly called the measure, which qualified in November for inclusion on the 2016 ballot, a “really bad idea.”

The tunnels have been a priority for Brown since he took office in 2011, and tension between the dueling factions has increased over the past several years, along with the governor’s urgency to get a deal done. That tension came to a head earlier this year, when the governor, who has said he had spent “millions of hours” poring over the details of the project, lashed out at the tunnel’s critics and told them to “shut up.” An aide quickly clarified that the governor’s remarks were made in “jest,” but Brown’s tone underscored the level of contention surrounding the plan. At an earlier news conference, the governor had called the project an “imperative” that “must move forward.”

Restore the Delta had taken particular offense to Brown’s comment.

“We will not go away, and we will not shut up,” the organization’s executive director Barbara Barrigan-Parilla said in a statement at the time. “We can’t stand by and watch a project move forward that’s going to destroy the most important estuary on the West Coast of the Americas or completely destroy California’s largest watershed.”

While the governor deals with the headache of trying to ensure a deal, California will also contend with more than 800 new laws that will be implemented in 2016, some of which will impact the state’s water issues.

And despite El Niño rains, the state’s crippling drought is nowhere near over, adding to Brown’s political burden.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.