Steelblue / Ferenstein Wire

*This post is part of a series on Silicon Valley’s political endgame from the Ferenstein Wire. See all available chapters here.

San Francisco is a living crystal ball of what happens when a city refuses to build enough housing to accommodate the dense clustering of high-tech and service workers natural to modern industries.

The median rent of a 2-bedroom apartment has skyrocketed above $3,500 per month, and over 12,000 residents have been evicted from their homes. All the while, the mayor’s office has dangled pricey carrots for tech companies to keep their headquarters in San Francisco, after the industry’s massive profits helped residents weather the recession with an envious employment rate of 4.8 percent and a 2 percent increase in wages.

One of the technology industry’s most significant transformations of modern life snuck up so slowly that it was hardly noticeable: The migration of jobs to big cities and the corresponding need to transform suburban neighborhoods into high-rise metropolises.

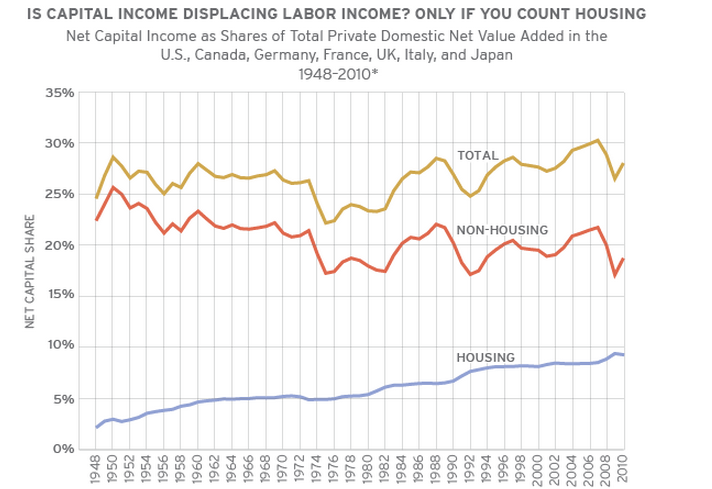

Indeed, a 26-year-old MIT economist recently turned heads with analysis showing that almost all income inequality growth over the last half-century can be blamed on the rising share of wages spent on housing (climbing an astounding 20 percent in 15 years, from 25 percent to 30 percent of income).

Source: Brookings Institute

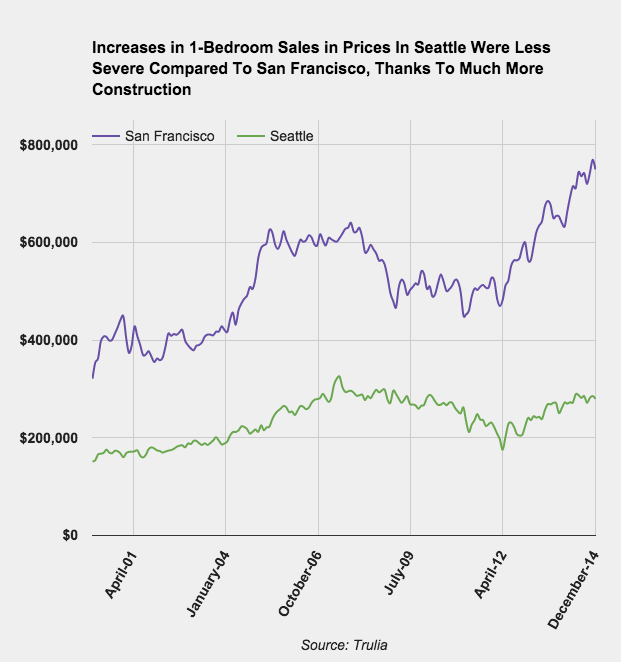

Of course, not every city suffers from high-tech growth. Berkeley Economist Enrico Moretti credits Seattle for blunting the forces of inequality by supporting their tech hub with a surge in new apartments.

(Data here)

To be sure, this trend isn’t new. For 5000 years of recorded history, cities have formed precisely to accommodate densely clustered high-skilled labor pools that thrive on innovative ideas, from the merchants of ancient Athens to the printing industry of the Renaissance in Paris.

Many of the most advanced capitals in each epoch of human history likewise had to invent new ways to house the flood of citizens seeking employment. Rome’s famous multi-story insula apartments are not so dissimilar to modern condos.

Source: Wikipedia

Now that the technology industry is a dominant economic force; dense cities have become both a major cause of and a solution to growing inequality. Density is popping up all over the world, often in unwelcome places. Suburban enclaves, blindsided by tech booms have resisted transforming their quaint neighborhoods into big cities.

But, Austin, Denver, and Brooklyn’s older suburban counterpart, San Francisco, may show that the twin forces of economic equality and density are too difficult to resist.

San Francisco at the Breaking Point

No city has experienced the rollercoaster highs of tech wealth and lows of housing scarcity like San Francisco. As the city reaches a breaking point, it is seeking radical measures to allow more housing.

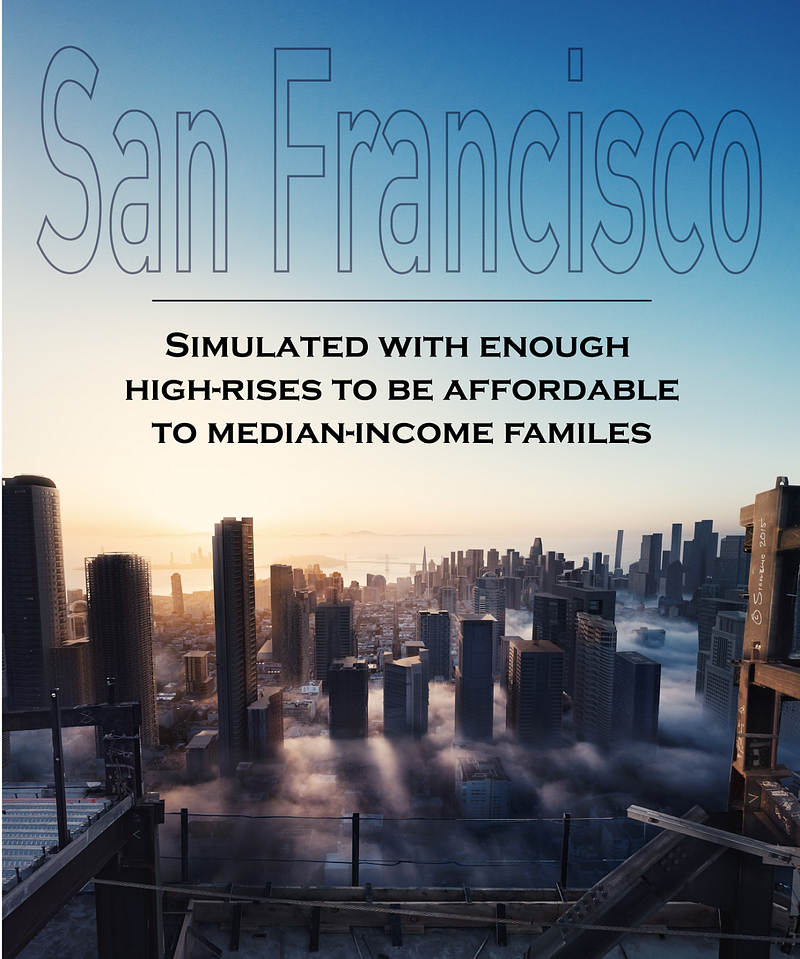

To simulate how suburbs around the country may eventually acquiesce to city life, I attained the first economic and visual simulation of how many apartment buildings San Francisco might need to construct in order to be affordable to median income households.*

“A 1% increase in housing stock results in a 10% reduction in price, all else being equal,” concludes Mark Zandi, Chief Economist at the influential financial institution, Moody’s (parent company of the rating group). He estimates that the entire Bay Area may need at least 130,000 more units in order to both remain affordable and house all of the tech jobs.

After constructing a simulation based on this model, I asked longtime San Francisco residents a simple question: Would they rather San Francisco be a Manhattan-like city with affordable rents or should Silicon Valley house their employees elsewhere and build their own city somewhere far away.

Reactions of the longtime San Francisco residents to these images (below) tell a story of those who have lived through the benefits of a tech boom and worry what might happen if tech money leaves the city.

Credit: Alfred Twu

Here’s what the famous Mission neighborhood will look like at street-level view:

Alfred Twu

Stacking Away Ghettos

“I like tall San Francisco with a mix of socioeconomic classes… it’s healthy for everyone; we don’t want ghetto areas,” said a San Franciscan of 15 years, Mission District resident, and Colombian migrant.

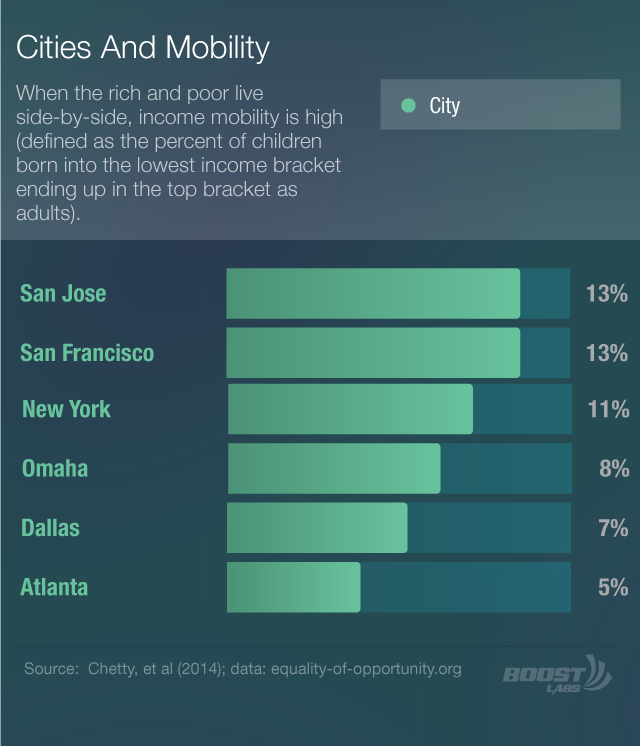

One of the most comprehensive studies ever done on inequality and economic mobility found that suburban sprawl is a key factor in financial disparity. Harvard’s Raj Chetty and his team discovered that the average child growing up in San Francisco will make $1,760 more as an adult than if they lived in the nearby commuting zone of Alameda County.

Even with sky-high inequality, San Francisco boasts of the nation’s highest social mobility for children born into the poorest income bracket. When the rich and the poor use the same schools, police, hospitals, and streets, ghettos are held at bay.

Rich Residents Make for High Employment and Wages

“I love the changes. Why? More people… more business,” says a Hispanic resident, who has been selling clothes on the streets of the Mission District for 20 years. She estimates that tech migration has boosted profits by 20 percent—“Of course, taller buildings.”

Cities may seem expensive, but suburban areas are far more costly. Eschewing the job opportunities of a city means giving up between 10–40 percent of one’s income. Economists find that housing prices drop proportionately with wages, the farther one lives from a large metro. Since the average American spends about 30 percent of his/her income on rent, an apartment in rural Wisconsin could cost hundreds (or thousands) of dollars more when factoring in wages.

“Our analysis suggests that the tech sector is responsible for the vast majority of the economic growth in San Francisco since 2010,” said San Francisco’s Chief Economist, Ted Egan. “In 2010–2012, the latest year we have complete data; local inflation has been 2.6%, while the wages for all workers have increased by 4.5%.”

Why? Berkeley Economist Enrico Moretti finds that Silicon Valley employment is an economic super-multiplier; every tech employee creates 5 new jobs in the area (compared to manufacturing industries which only create two). Tech industries not only cluster high-skill workers but the legal and service workers that keep their employees coding all night long.

No Cities? Commute

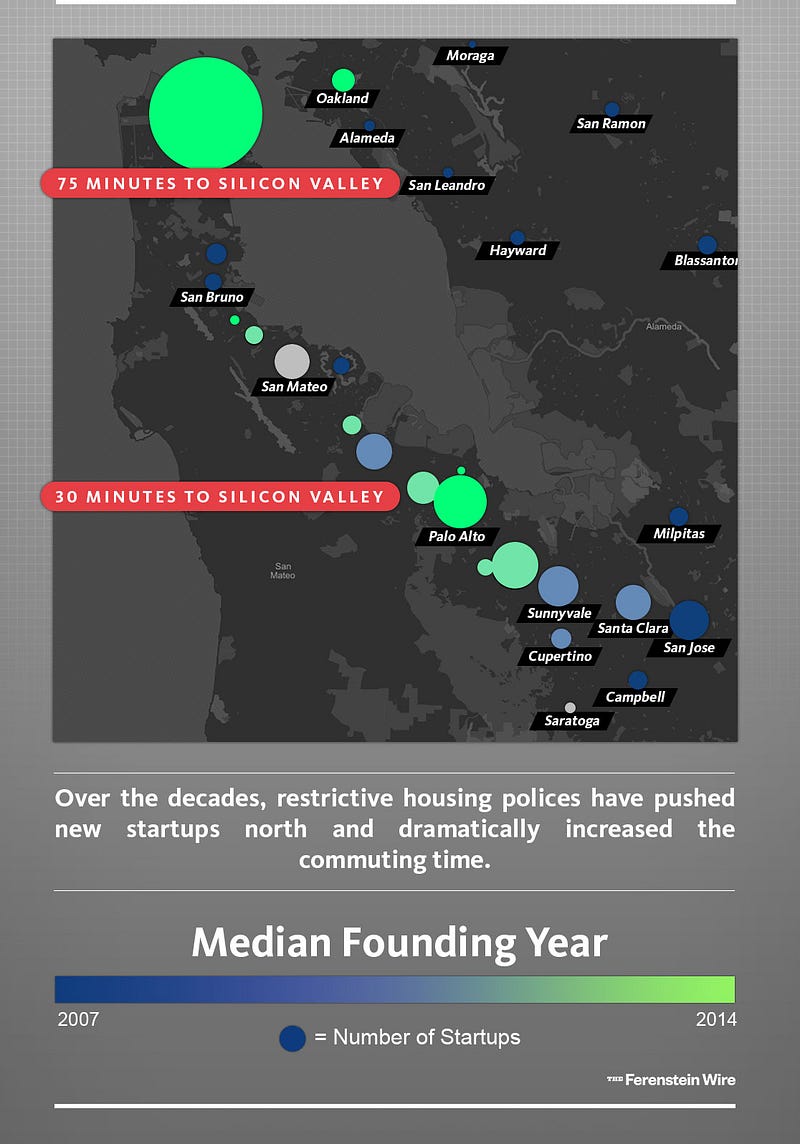

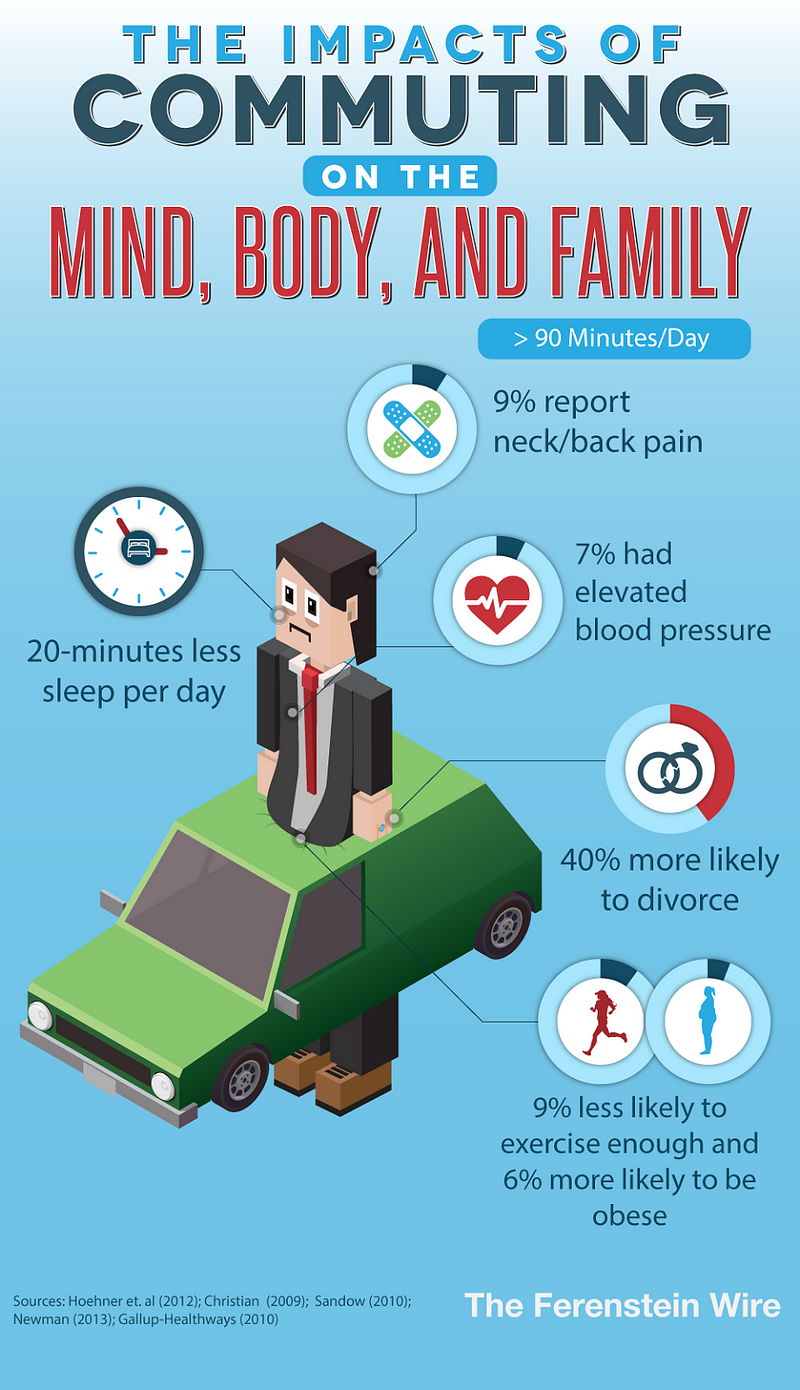

The alternative (California’s current solution) is commuting, as tech companies and their tens of thousands of employees are scattered throughout the peninsula, forced to find shelter anywhere they can.

The Bay Area suffers from one of the worst commutes in the country. For decades, Silicon Valley’s suburbs have refused to accommodate high-rise apartments for tech workers and their massive campuses, which have slowly been pushed up north, from San Jose to San Francisco.

Commuting hurts the poor and minorities most, who have been pushed away from jobs as the rate tripled the national average [PDF]. In California, one Stanford dining employee describes waking up at 3am for his 80-mile commute each day.

End of Government Support for Suburbs

Both California and the Obama administration have come under fire for policies that punish restrictive suburban zoning as a solution to racial and economic inequality.

“It’s time the federal government stopped encouraging sprawl… we learned from the housing crisis that home ownership is not for everyone,” said Former Housing and Urban Development Secretary, Shaun Donovan, whose administration supported the controversial Bay Area plan, which called for upwards of 68 percent of new development to be condo-style density.

“California Declares War On Suburbia,” stated a Wall Street Journal headline. But California may be charging ahead with a new, more urbanized path anyways.

“All options need to be on the table. If a taller, denser San Francisco will make the city more affordable, then it’s time we study how to make that happen,” says Mission District Supervisor David Campos, who has, in the past, supported some of the most restrictive zoning laws in San Francisco history. For Campos, density may be the only way his residents can keep their homes.

Campos may be reading the political tea leaves correctly: I ran a small zip code-targeted public opinion poll showing simulations of a taller San Francisco to respondents and found that a slight (statistically insignificant) majority of residents support a Manhattan-like city landscape if it meant affordability (data here).

As America reaches a crisis point, it portends a future where, for the sake of equality, humanity will become a more urbanized species.

Indeed, one demi-billionaire, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh, has spent his personal fortune figuring out how to design a city for optimal density, allocating $350M to transform downtown Las Vegas into a model for the world.

City champions argue that we will look back on suburban sprawl as an aberration in human history. As Harvard Economist Edward Glaeser predicts:

I suspect that in the long run, the twentieth-century fling with suburban living will look, just like the brief age of the industrial city, more like an aberration than a trend… our culture, our prosperity, and our freedom are all ultimately gifts of people living, working, and thinking together — the ultimate triumph of the city.

*For more stories on this series click here to be notified as soon as chapters become available.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.