The Carlsbad Desalination Project will be the largest facility of its kind in the Western Hemisphere when it opens later this year.

Situated 35 miles north of San Diego in Carlsbad, California, the $1 billion plant will supply 50 million gallons of potable water per day, or about seven percent of the county’s total water needs, to drought-weary San Diego County residents when it comes online around Thanksgiving.

With California’s snowpack at historically low levels, groundwater depletion causing subsidence across the Central Valley, and a frustrating lack of significant rainfall, much attention has been focused on desalination as a solution to the state’s record drought.

For decades, advocates and critics of desalination in California have clashed over the efficiency and cost of the process. Supporters claim desalination could tap the limitless water supply of the Pacific Ocean to alleviate the acute water shortages caused by drought, while opponents, including many of the state’s politically powerful environmental groups, say the process is too expensive and degrades the ecology of the ocean.

For supporters of desalination, the opening of the Carlsbad facility represents a chance to prove to even the most ardent critics that the process can play a big role in California’s long-term drought solution.

“The Carlsbad desalination plant marks a milestone, an important step in securing California’s future and its water supplies,” Abdullah Al-Alshaikh, president of the International Desalination Association, told the Los Angeles Times. “The Pacific Ocean is a sustainable water source that won’t run dry.”

The International Desalination Assn. (IDA) will hold its World Congress at the San Diego Convention Center near Carlsbad later this summer. For the international cadre of utility companies, consultants, engineers, and desalination experts that will fly in from around the world, the five-day conference represents the first opportunity for many in the industry to get an up-close look at the new facility.

For the IDA, San Diego represents the “undisputed birthplace of commercial reverse osmosis” and the “epicenter of desalination and water reuse development in the USA.”

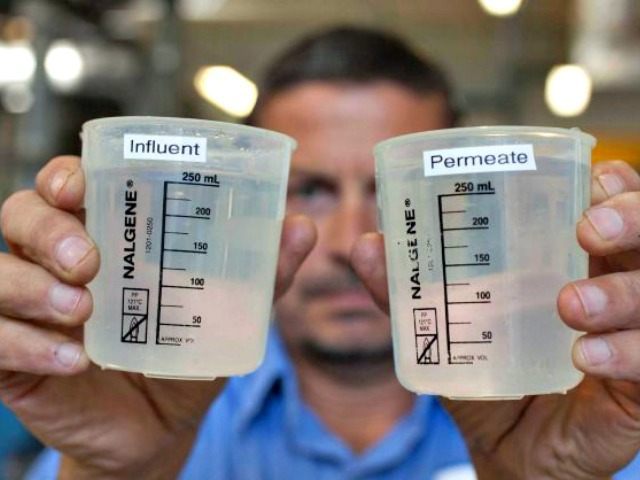

The Carlsbad desalination plant will use reverse osmosis technology to push Pacific Ocean saltwater through membranes that filter out the salt and convert it into potable water. According to the Times, Boston-based Poseidon Water, builders of the Carlsbad plant, were assisted in upgrading the plant’s technology by Israeli water companies, including IDE Technologies, which previously built the largest desalination facility in the world, the Sorek facility, in Israel.

Poseidon faced years of protracted legal battles in constructing the Carlsbad facility, from both environmental groups and state and local permitting agencies like the California Coastal Commission and the Carlsbad City Council. According to the San Jose Mercury News, the facility’s backers successfully fended off 14 lawsuits from environmental groups before work began on the plant in December 2012.

The delay hasn’t caused Poseidon Water vice president Peter MacLaggan to lose optimism.

“Carlsbad is going to change the way we see water in California for decades,” MacLaggan told the Times. “It’s not a silver bullet to solve all our water problems, but it’s going to be another tool in the toolbox.”

Still, with the opening of the plant just a few months away, environmental opponents of the project, including former Surfrider Foundation policy coordinator Joe Geever, say desalination should be considered only after all other options are exhausted.

“Carlsbad is the horse that got away,” Geever reportedly said at a recent State Water Resources Control Board meeting. “Let’s make sure it’s not repeated.”

Geever’s Surfrider Foundation and other environmental groups had used lawsuits to delay construction of the plant for years. Environmental groups say that the facility’s intake pipes, borrowed from the Encina Power Plant next door, will suck up small fish and microorganisms from the ocean and disrupt its natural ecosystem.

According to the Mercury News, Poseidon Water’s permit to build the facility was conditioned on its building of 66 acres of wetlands in San Diego Bay to offset the environmental harm the plant could cause. Additionally, the Carlsbad facility will probably be the last in California to use “open-ocean” intake pipes; future facilities, including another planned Poseidon facility in Huntington Beach in 2018, will likely be forced to place intake pipes closer to the sea floor, where damage to fish and other marine life will be minimized.

But critics of desalination have pointed to other factors in their critiques of the Carlsbad facility.

The plant’s reverse osmosis process will use approximately 38 megawatts of energy, or enough energy to power 30,000 homes, to push 100 million gallons of seawater through the membranes to produce potable water. The facility will produce one gallon of potable water for every two gallons of salt water it treats, and the costs, both in energy and in real dollars, are much higher than other methods of obtaining water like building reservoirs or reusing wastewater.

The San Diego County Water Authority signed a 30-year deal with the Carlsbad facility in which it agreed to pay between $2,014 to $2,257 per acre-foot of water with a minimum purchase of 48,000 acre-feet of water per year. Water Authority lead engineer and water resources manager Bob Yamada predicts the cost of San Diego County’s 3.1 million residents’ water bills will go up between $5 to $7 to help pay for the desalinated water.

Other fears lie in the possibility, however remote, of an abrupt end to California’s drought. With facility construction and permitting stalling for years, critics say newly constructed desalination plants could become instantly obsolete if rain and snowpack quickly return to the state.

That exact scenario happened to the Charles E. Meyer Desalination Facility in Santa Barbara. Built for $35 million in the late 80s during another formidable California drought, the plant closed in 1992 after heavy rains replenished the city’s reservoirs, negating the need to keep it open.

Now, with the city’s main reservoir, Cachuma Lake, hovering at around 30 percent capacity for the last several months, Santa Barbara will spend another $40 million to reopen the mothballed facility, plus an additional $5.2 million per year to maintain it. Supporters, however, can point to an encouraging estimate that, once online, the facility will satisfy a full 30 percent of the city’s water needs with desalinated ocean water.

With the stakes high for both San Diego County and the larger desalination community, San Diego County Water Authority’s Yamada remains optimistic.

“We are very confident that Carlsbad is going to operate successfully,” Yamada told the Times. “We’re going to have a world-class facility.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.