CARACAS, Venezuela – The death of dictator Hugo Chávez on March 5, 2013, marked a before and after for Venezuela’s socialist regime.

Ten years later, Venezuela is far from what it used to be – courtesy of the collapse of socialism, a ceaseless parade of crises, periods of intense turmoil and repression, and the culminating worst migrant crisis in the region, rivaled in the world only by Ukraine’s.

The Maduro regime commemorates March 5 as one of the holiest of the country’s national holidays, more prominently than even the death of founding father Simón Bolívar on December 17. Yet for Venezuelans, there is little to celebrate in Chávez’s legacy.

As this past March 5 marked the tenth anniversary of Chávez’s death, and Maduro’s rise to the position of socialist dictator, the Venezuelan regime had a few things in store. Maduro himself started things up on the evening of March 4 at the state-owned Humboldt Hotel, a luxury facility at the top of the Ávila National Park that is out of reach for the majority of Venezuela’s impoverished citizens.

The regime’s March 5 acts included fireworks to honor the socialist dictator, the debut of a new propaganda documentary, and a caravan that culminated with a gathering at Chávez’s resting place that featured regime officials, leftists, and “emblematic” international guests and allies – such as Nicaraguan dictator Daniel Ortega, communist Cuba’s Raúl Castro, and Ecuador’s former President Rafael Correa.

It’s important to note that, as part of the Bolivarian Revolution’s cult-like “pseudo-religion” and ever-so-tiresome rhetoric, high-ranking members of the Revolution do not “die” per se. To this day, the Maduro regime will tell you that, at least in an ideological sense, Hugo Chávez did not die on March 2013 of cancer, but rather, he was “sown” on that day — in other words, he “stepped” or “jumped” into immortality. Basically, any other verb works as long as it avoids saying that Chávez is indeed dead, and he’s not coming back.

Communist regimes, from Cuba to North Korea, have long used similar rhetoric, refusing to admit the deaths of their most powerful figures and granting them political offices beyond the grave. The socialist regime here did the same thing: posthumously elevated Hugo Chávez from his position as “Commander-President” of the Revolution to “Supreme and Eternal Commander” of the Revolution.

Given his status as the leader and founder of the Bolivarian Revolution, it should not come as a surprise that the regime spared no expense on his final resting place, the Cuartel de la Montaña 4F (“4F Mountain Barracks”). This place, built in the early 1900s and originally known as the “The Military Historical Museum of Caracas,” was rechristened in 2002 by Chávez to “honor” his failed coup attempt on February 4, 1992, as this was the place he hid at once his coup failed and ultimately surrendered.

Soldiers stand guard next to the tomb of late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez on the 10th anniversary of his death outside the Cuartel de la Montaña 4F in the 23 de Enero neighborhood of Caracas, Venezuela, on Sunday, March 5, 2023. (Carlos Becerra/Bloomberg)

So Chávez left his own regime the “perfect” important place in its mythos to build their leader’s mausoleum, instantly becoming the ultimate pilgrimage destination for the socialist party’s adherents and leftists visiting Venezuela. Currently, the site serves as a museum of all things Chávez, an altar to the architect of the modern Venezuelan disaster.

Unfortunately for the socialist regime, the Cuartel de la Montaña’s initials, CDLM, happen to be shared by a rather vulgar expression in Venezuela that, while commonly heard in everyday life here, I’d rather not repeat here — so, in a way, you could say that Hugo Chávez is buried in the “CDLM” is a very accurate and fitting double entendre.

That’s something you have to be careful to laugh at though, as police could interpret jokes of that nature as “hate speech” and throw you in prison for 20 years.

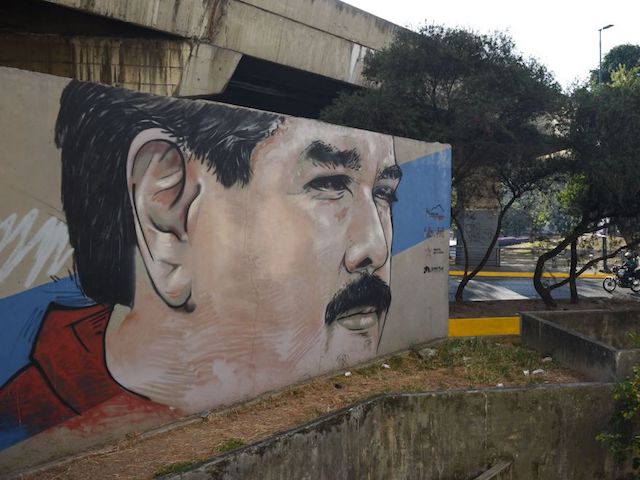

Other events included transporting Chávez’s military cadet sword to the CDLM so that it can be “worshiped” as a relic, turning the house Chávez spent his early years in into a museum, and plastering Caracas with even more Chávez murals and art.

Picture of a mural depicting Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro in Caracas, taken on March 2, 2023. (MIGUEL ZAMBRANO/AFP via Getty Images)

Men on motorcycles ride past a mural depicting Venezuela’s late President Hugo Chavez (1954-2013) in Caracas, Venezuela, March 2, 2023. (MIGUEL ZAMBRANO/AFP via Getty Images)

The sanctifying of allegedly historical artifacts and homes is meant to further elevate Hugo Chávez to the same level of prestige as Venezuelan independence hero Simón Bolívar, whose birthplace house is a historic landmark of Caracas.

Bolívar (1783-1830), often referred to as “El Libertador” (“the Liberator”), was a Venezuelan independence hero born in Caracas that spearheaded the independence of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia — which is named after him — from Spain’s colonial rule.

Bolívar hoped to unite all South American nations into a single one, with his plans briefly materializing into what used to be known as Gran Colombia, a single nation that lasted between 1821 and 1831 and was composed of what is today Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela. Venezuela’s national currency, the bolívar, is named after him.

In 2010, Hugo Chávez ordered Bolívar’s remains to be exhumed in an unusual, late-night procedure broadcast live. Chávez strongly believed that Bolívar did not die of tuberculosis as all historic records state — but rather, that he had been poisoned. Although the socialist regime spared no expense, and the investigation’s results did confirm that the remains belonged to Bolívar, they could not prove Chávez’s theory.

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (L) holds hands with Venezuelan Presiden Hugo Chavez in front of a portrait of Simón Bolívar at Miraflores presidential palace in Caracas on November 25, 2009. (JUAN BARRETO/AFP/Getty Images)

The socialist regime took advantage of the exhumation of Bolívar’s remains to commission a computer-generated “recreation” of Simón Bolívar based on his skull, presented by Chávez himself months before his death. Detractors of the socialist regime often accuse it of having deliberately commissioned the results of the computer-generated portrait to make it loosely resemble Chávez. The new portrait greatly differed from historical depictions of Simón Bolívar, most prominently from a portrait by Peruvian painter José Gil de Castro in 1823 that Bolívar himself said in a letter was the one with “the greatest accuracy and likeness.”

The socialist regime’s “profanation” of Bolívar’s remains gave forth to an urban myth, as many considered that the regime’s acts unleashed a “curse” on Chávez and some of his allies. Shortly afterwards, several high-ranking regime officials died in traffic accidents, from heart attacks, and other health complications. Chávez himself was diagnosed with cancer one year later.

Replicas of Bolívar’s sword are among the highest honors you could receive from Venezuela. Unfortunately, just like Chávez did in the past, such honor has been grossly tainted by Maduro, who has indiscriminately given it away to ideological allies as it sees fit, including Vladimir Putin in 2019.

Just as it has hijacked the symbols of Bolívar’s legacy, so too has the “Bolivarian Revolution” shoehorned Chávez into Venezuela’s religious tradition, especially during the first few years that followed his death. Some examples include Maduro deifying Chávez by claiming the dead dictator had “returned” in the form of a bird to bless him, commissioning a cartoon that depicts Chávez “arriving to Heaven,” and rewriting the Lord’s Prayer in 2014 to begin “our Chávez who art in Heaven.” The latter was highly controversial and poorly received in majority-Christian Venezuela.

The Maduro regime sobered up the religious act as time went by — moreso after socialism resulted in a near-total collapse of the country’s government and economy.

The “Saint” Hugo Chávez chapel built a few years ago to venerate the dead socialist dictator has slowly but surely faded into obscurity, as the fervor for this socialist figure is simply not what it was.

Some of the more hardcore leftists in the country still cling to Chávez by blaming Maduro for the impoverished state of the country, insisting the former bus driver dictator “is not Chávez.” The critique ignores that all Maduro has done is to follow Hugo Chávez’s 2013-2019 socialist Fatherland Plan, which he turned into a law.

Speculation regarding the date of Chávez’s death is also part of a lesser-known conspiracy theory in Venezuela. Officially, Chávez died on March 05, 2013. However, Venezuela’s former Chavista attorney general Luisa Ortega Díaz, who defected from the regime in 2017, claimed in 2018 that Chávez had instead died on December 28, 2012, days before the start of his fourth term.

This unconfirmed “theory” initially began spread when the socialist regime abruptly suspended New Year’s celebrations in December 2012 and postponed the swearing in ceremony for Chávez’s fourth presidential term, a mandatory public act according to the country’s constitution. Regime officials fabricated new conditions on the fly to minimize the constitutional requirements.

If the conspiracy theory is true, everything that Chávez allegedly did between January and March 2013 would be null and void — and he never started his fourth term. Ortega Díaz’s statements came years after the theory had long since faded from the collective public opinion. No regime official ever confirmed or denied the comments, nor did anyone in the country’s “opposition.”

For me, as a regular Venezuelan, March 5 was just another Sunday this year. I had zero desire to give the pseudo-holiday any importance. While the Maduro regime mourned once the passing of their leader, I have my own mourning to do: this month marks the fifth anniversary of my mother’s passing. She died on March 31, 2018, of cancer – just like Chávez. Due to the collapse of socialism, she was not able to receive potentially life-saving chemotherapy. Like many in the country, she never had access to the kind of treatments and conditions that Chávez received in his own fight against cancer.

In a way, Chávez indeed was “sown” or whatever the regime keeps insisting on, as while he’s no longer physically in this earth, the consequences of his “socialist dream” are something we continue to pay the price for. He, ultimately, put us in this mess.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.