Venezuela’s socialist revolution will soon mark its 24th year in power on February 2. The historic tragedy that has befallen this country has dramatically changed our culture in nearly every way, and our daily lexicon is no exception.

I was barely 11 years old when they took power in February 1999 and now, with February 2022 right around the corner, I’m 35 with some gray hairs on my beard already.

During that time, the ever-evolving and constantly worsening political crisis in Venezuela left us with tragedies, traumas, and so many other things that all I can do is hope that our mistake never comes to pass in another country.

The rise of Bolivarian socialism, its inexorable collapse, and its now stagnant phase left us with new additions to our vocabulary — either forced or genuinely coined — that we’ve been using to define the modern Venezuelan reality.

These words and acronyms evoke an array of emotions and memories, depending on who you ask. Some of these are phased out, while others still remain fresh and are used to this day, but all of them serve to remind us of how this ongoing socialist revolution has changed us forever.

Perhaps, you now find yourself working or living next to a Venezuelan — after all, there are now over 7 million of us spread around the world thanks to socialism and, if I may be candid with you, I’m aiming to be part of that statistic in my near future, God willing. Hopefully this pocket guide, featuring some of the most emblematic “colloquial” Venezuelan words stemming from the political crisis, serve as a way to understand these now very Venezuelan words and terms.

Migrants, many from Central American and Venezuela, walk along the Huehuetan highway in Chiapas state, Mexico, early June 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte, File)

First and foremost, and by far, the most significant word that the Bolivarian Revolution seared into our minds has to be the word escuálido, or “Scrawny One.” The word escuálido was not invented by the revolution and is part of the Spanish language, but Hugo Chávez took it upon himself to co-opt it for pejorative purposes.

To this day it is still used to describe anyone that is either ideologically opposed the revolution or simply does not agree with it, regardless of whether you’re part of the “opposition” or not.

An escuálido is, for the socialist revolution, the antithesis of a chavista, his ideological counterpart. In my youth, during the early years of the revolution — before the revolution dialed socialism to eleven circa 2006 — to be an escuálido also meant that you were not with “El Proceso” (the Revolutionary Process).

Perverse as it may be, the revolution was and is still very adept at the use of nicknames and adjectives to discredit and ridicule any dissenting figurehead — a feat that’s easier to accomplish when you’ve effectively banned political satire. The term “deplorables” wishes it would have had a fraction of the effect escuálidos had throughout the years.

Another term stolen by the revolution from its Puerto Rican origins is pitiyanqui, or “Petit-Yankee.”

The revolution uses this neologism to discredit anyone who may or may not have ties with the United States, or someone who is simply neutral towards America. The term is still used here and there by members of the Maduro regime, and even in military chants to rally against an alleged U.S. invasion.

I distinctly remember that the Venezuelan “opposition” once tried to counter it with the term piticubano, referencing the revolution’s adoration of the communist Castro regime and dictator Fidel Castro, who was alive at the time. However, they did so clumsily, and they definitely missed the mark.

Still, people found adjectives to ridicule the revolution on their own without the need for the “opposition” throughout the years. Hugo Chávez, who was posthumously elevated to “Supreme and Eternal Commander of the Revolution,” has been conferred the title of El Galáctico (“the galactic one”) and El Mortadelo — referencing the fact that he is, indeed, dead, unlike what the revolution’s rhetoric professes. In socialism, leaders don’t “die” – they’re “sown” into the land. Sometimes, you can use both, and just call Chávez El Mortadelo Intergalactico.

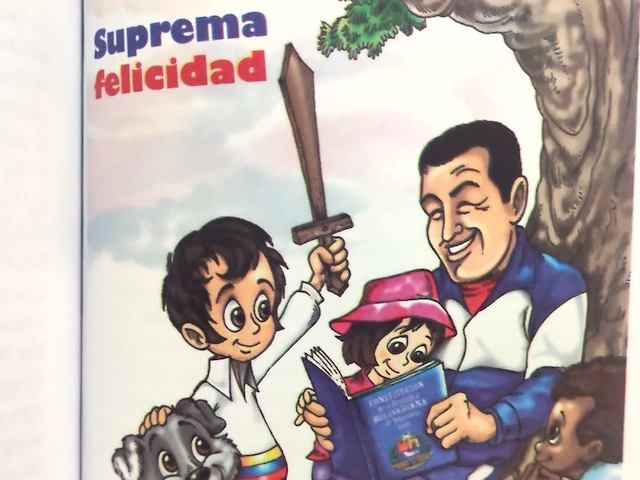

A copy of an illustrated children’s Venezuelan constitution featuring Children and a dog sitting around late dictator Hugo Chávez. The caption reads “Supreme Happiness.” (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News)

Diosdado Cabello, Socialist party strongman and alleged drug lord, used to have a nickname of his own too, but before I can explain that one I need to explain the term guiso or “Stew.”

In Venezuelan politics, when a public official is making a guiso, that doesn’t mean that a person is going to cook a stew — unless by “stew” you mean a shady and corrupt business, embezzling public funds, and that sort of stuff. A guiso for us is something akin to the idiom “cooking the books” – presumably, a reference to the “stew” being made with the books.

Back in the day, Cabello was referred to as pimentón or red pepper. Why? Simple: because a red pepper is never missing from a guiso recipe. It’s probably opportune to remind readers that the United States has an active $10 million bounty for information leading to the arrest and/or conviction of Diosdado Cabello Rondón.

Nicolás Maduro talks with Diosdado Cabello upon their arrival at the swearing in of the members of the campaign command for the constituent assembly, in Caracas on May 29, 2017. (FEDERICO PARRA/AFP/Getty Images)

The color red, often synonymous with socialism and communism, would not get exempt either, and the term rojo rojito, (“reddy red”), coined by socialist party strongman Rafael Ramirez in 2006 when he was the head of the state-owned PDVSA oil company to refer to the “new” oil company, which had to be unquestionably loyal to Hugo Chávez and the revolution.

Ramirez had used the term in a speech meant to be private, but recorded and publicly published; some copies of the video can still be found online. Ramirez would eventually fall from grace with the Maduro regime and now lives in exile in Italy.

The Venezuelan “opposition” would not get a “power word” like escuálido until the 2010s, when perennial “opposition” candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski, after being branded as a majunche (of inferior quality, lackluster, mediocre) by Hugo Chávez during the 2012 presidential campaign, coined the term enchufado, or “plugged-in.”

To be an enchufado means that you’re plugged into one of the many outlets of the socialist machinery. It is the ultimate aspiration of every card-carrying member of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) to reap some sort of benefit — be it political or economical — that can only be attained through these means, such as attaining an important position among one of the many Venezuelan “People’s Ministries.”

The potential benefits that come with being “plugged in” in no way can compare or compete to the lavish lifestyle that only comes with being a high-ranking member of the Maduro regime. Enchufados also cannot hope to compare to the lifestyle of a term that’s less used these days: the boliburgueses (Bolibourgeoisie, a portmanteau of the words “Bolivarian” and “bourgeoise”), a nouveau riche caste of corrupt rich socialists and that made their fortune through shady businesses and stealing Venezuelan money. Many of them prefer to live in the comfort of American capitalism than in the misery of socialist Venezuela.

Don’t forget though, being rich is bad — unless you’re a socialist.

Henrique Capriles Radonski may be the most reviled “opposition” politician in the country, who has even called for an end to sanctions on the Maduro regime, but credit where it’s due: coining the term enchufado is his political magnum opus.

Another set of terms that used to be common in Venezuela happened to involve the United States dollar, a currency far more important than the Venezuelan bolivar, which has so far died three deaths since 2008.

6,800 Bolivars — roughly worth $0.00161 on August 25, 2021. These are from the Bolivar Soberano series (2018 – 2021). Currently worth about $29.63 after Maduro dropped multiple zeroes from the currency’s value. (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News)

Between 2010 and 2018, there was a law that heavily punished the use of foreign currencies, going as far as to actually punish people for daring to speak about the existence of exchange black markets. When it was highly illegal to mention the dollar, we had to come up with new terms to refer to it, as even marketplace websites such as MercadoLibre had to implement systems that would flag publications if they so much used the word “dollar.”

Over the years, we began to refer to dollars as lechugas (“lettuces”) or lechugas verdes (“green lettuces”) to differentiate it from the “European” lettuces (the Euro).

When websites caught onto that and began censoring the word lechuga, some began calling dollars “Obamas” and then Trumps. Unfortunately for President Joe Biden, his last name is not something we need to use to refer to the American greenback anymore.

The irony of all of this is that, despite everything the revolution did to demonize the American currency, it is the one thing it can’t get enough of and the one thing keeping the country together.

Lastly, these words are not terms themselves, but rather, the names of public offices of the Maduro regime that no Venezuelan will ever have fond memories of.

SAIME (the Administrative Service of Identification, Migration and Foreigners) is a name that strikes the purest dread into the hearts of every living Venezuelan. It’s the public office that handles everything related to one’s identity documents, such as our I.D. cards (which you need for literally everything here), and passports (which cost $215 and are very much needed if you want to flee from socialism).

If one were to adapt The Divine Comedy for Venezuelan audiences, then SAIME would be one of the nine circles of hell, where you have to wait hours and hours to get your documents – and it might take months to get if you’re not lucky.

Right now, SAIME is the last thing preventing me from simply just packing my things and boarding a plane out of the country. Just to give you an idea, I had to wake up at 1 a.m. on January 16 just so I could be fifth in line with my brother by the time they opened their doors at 8 a.m. Maybe I’ll get lucky and I get my documents in February, maybe in March. Who knows?

Other offices like SAREN, the Autonomous Service of Registries and Notaries, and the regime’s apostille system — whose website you can only enter on specific days according to the last number of your Venezuelan ID card — are equally dread-inducing, as these bottlenecks can often become huge obstacles if you want to leave the country with all your documents in order.

The names of the public utilities are worthy of mentioning too, for their very much lackluster services have caused us to curse and swear at them beyond measure — such as such as CANTV (state-owned internet), CORPORELEC (the national power company that by October 2022 had given the country 29,418 blackouts) and, in my case, HIDROCAPITAL, the self-styled “tool of the revolution” water company that just left me one week without water.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.