CARACAS — The socialist regime of Venezuela recently began its Chinese Coronavirus mass vaccination plan, featuring inhumanely long lines, limited doses per day, disorganization, frustration, problems with the vaccine appointment system, corruption, and much more — all characteristic facets of socialist mismanagement.

Yours truly went through the experience of a lifetime, spending almost 12 hours waiting in line for his appointment to no avail.

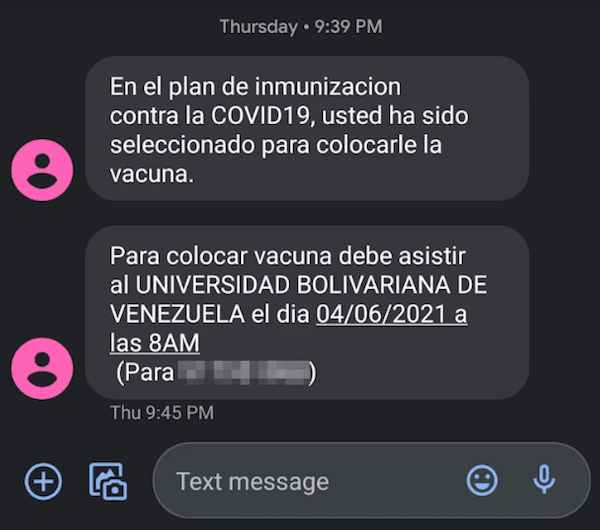

The particular exercise in futility that I’m about to narrate occurred on the premises of the Bolivarian University of Venezuela, located in Los Chaguaramos, Caracas. It all began on the evening of June 3, where I received a text message from the socialist regime’s Fatherland System, a system largely inspired by China’s social credit score system and built with the assistance of the Chinese company ZTE.

A text from Venezuela’s Fatherland Card system reading “In the immunization plan against COVID19 [Chinese coronavirus], you have been selected for a vaccine. To receive vaccine please go to BOLIVARIAN UNIVERSITY OF VENEZUELA on 04/06/2021 at 8AM.” (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News)

I must confess that I was rather wary of even going in the first place, but the looming suggestion of vaccine passports was what ultimately convinced me to go. I have been trying for the past three years to migrate legally — to be thwarted at the eleventh hour for not having a vaccine would be most disheartening.

The appointment message said 08:00 a.m., so I was there before 07:30, along with two members of my family that got the same message sent to their phones. Living in this country prepares you for the fact that there ought to be people already waiting in line by the time you arrive — what I did not expect, however, was to find nearly 1,000 people in front of me.

People were split into three lines: one for the elderly (60 years old and older), one for healthcare workers, and one for everyone else. All received the very same appointment message I got, down to the very same hour.

The media was initially not allowed on the premises that morning. That did not stop those that were part of the line from taking pictures whenever possible, including yours truly.

Line for coronavirus vaccines at the Bolivarian University of Venezuela in Caracas, June 4, 2021 (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News).

Aerial videos and pictures taken by citizens that lived in nearby buildings serve as a reference on just how massive the line was, which extended for over a block.

Unlike in the United States, where citizens can opt to get the vaccine of their preference – such as those developed by Pfizer, Moderna, or Johnson & Johnson – in socialist Venezuela, the choice is made for you. Russia’s Sputnik V is the vaccine assigned for everyone 60 years or older. China’s Sinopharm is the one assigned to everyone else — take it or leave it.

And thus I began to partake in the most socialist of all pastimes: waiting in line for something. Representatives of the area’s Communal Council (civilian organizations that answer to the socialist regime) began to elaborate their own list of attendees, separate from the list presumably created by the Fatherland system. One of them gave up before I had arrived. The other called it quits after the 830th or so person. The line moved at a snail’s pace, getting stuck more often than not.

Sometime during the first couple hours, word began to spread that a member of the National Guard was telling everyone that due to a “glitch” in the Fatherland System, a considerable amount of appointments were sent by mistake. The news website maduradas.com alleges that 10,000 people received an appointment text similar to the one I got. Everyone was justifiably upset at this.

It is worth mentioning that this massive exterior line was not the one to get the vaccine. This was the line to enter the makeshift center where the vaccines were being administered. Your reward for enduring this torturous line was – you guessed it – another line.

When it was close to 02:00 p.m., the National Guard began to inform everyone in line that there were no more available doses of Sputnik V for the elderly, so every remaining elderly man and woman in those lines, who had already wasted an inhuman amount of hours in line, had no choice but to leave.

To make matters worse, everyone else was told that only 350 people out of the nearly thousand remaining were to receive the Chinese Sinopharm vaccine that afternoon. I couldn’t see it, but you could hear the cacophony of disappointed voices emanating from way further back in the line.

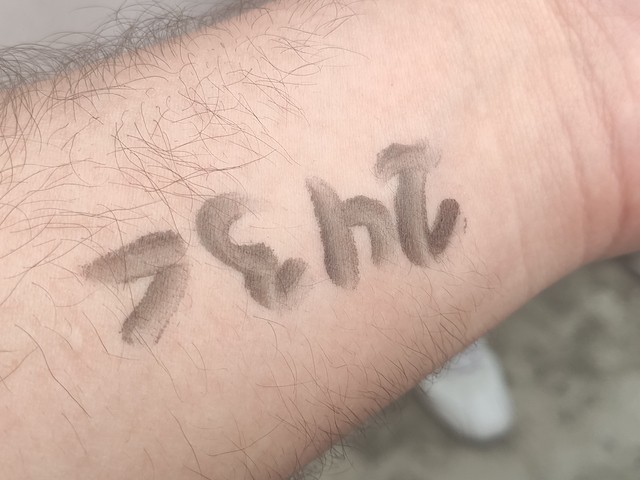

And from that moment, staff began to mark people like cattle using a marker pen — a humiliating trick employed by the socialist regime for the distribution of regulated products during the worst days of Venezuela’s food shortages.

The branding process was suspended after the 80th person or so because the marker ran out of ink.

I’ve often been asked, “how is your country even real?” and I just have no answer for it, it just is.

So, for this line, I was number 243C out of 350. The C stands for Chinese [vaccine].

Arm marking to receive coronavirus vaccine in Caracas, Venezuela. June 4, 2021. (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News).

It would not be a true socialist line without some corruption going on. Throughout the day, many were allowed in without enduring the line, as these came recommended by a “friend” in the United Socialist Party, getting slipped past whenever possible.

The inclement summer sun and the breezeless 82-84°F temperatures subsided for a moment thanks to a respite given by the clouds in the sky, but to add insult to injury, a brief rain began to pour shortly afterward. I found shelter under a small roof of a private parking spot nearby and ended up getting partially wet. I wasn’t concerned about losing my spot in the line – that’s what the branding was there for.

The hours kept passing and the collective stress, exhaustion, and insolation began to take their toll. By the time I was nearing my eighth hour in line, the whole process was stalled because the staff was on their lunch break. While some conversed with one another, others began to sit on the street, find ways to stretch, or make trips to the beginning of the line in hopes of finding some good news.

During that time, certain media outlets, such as the Voz de América, were able to slip past and briefly interview some of the frustrated people in the line. Moments later, men in civilian clothing began to impede the work of the media reporting in the area — moreso after citizens began to denounce that members of the National Guard were demanding payment to let people slip into the center.

Line for coronavirus vaccines at the Bolivarian University of Venezuela in Caracas, June 4, 2021. (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News)

Close to 06:00 p.m., a representative of the National Guard came out to tell the remaining marked people that no more people were to be allowed in, as there were no more available vaccines due to a “miscalculation” of the number of available doses — even though people had been branded and numbered hours ago. Those that were part of the line began to feel outraged and attributed this supposed miscalculation to the fact that random people were allowed to slip in throughout the day.

The crowd began to raise their voices and demand to be allowed in. In response, the National Guard said that those left outside were to be added to a new “priority list” and receive priority treatment on the next day — for which they should start lining up at 05:00 a.m.

Things got slightly heated, but ultimately, everyone, myself included, were too exhausted to do anything about it — not like there was much the unarmed, starved, isolated, and worn out crowd could do against the police and militia roaming the area and inside the premises of the University.

Some complied and signed up for the list, others gave up. After nearly 12 hours of waiting in line, I got no vaccine. I did, however, get a moderate to serious sunburn in my face, neck, arms, and hands — as well as the aches that come with standing in line for that long.

I refused to go the next day; the two members of my family did. They went there at 05:00 a.m. as instructed and were part of the “priority” line. They both ended up getting their first dose of the Chinese Sinopharm vaccine at nearly noon. An elderly couple that lives in my building went at approximately 07:00 a.m. and received their shots past 05:00 p.m. I may not be the most educated person out there, but I know this is way past inhumane treatment, especially to the elderly.

This is but one tale, in one line of over 1,000, in one center out of many. Across the country stories of a similar disaster continue to proliferate as the days go by.

An endless vaccination line is but another displeasing line that I have to add to the list of lines that I’ve had to do thanks to socialism: bread, medicine, bar soap, oil, rice, flour, car batteries, gasoline, among many others. I refuse to make my brother (who due to his mental condition is under my care) go through this whole torturous process.

At this point, I’ll wait it out and see if things improve — but I don’t have my hopes up. Worst case scenario I’ll just have to pray I don’t get thwarted for not having a vaccine passport when I finally obtain a visa that lets me migrate out of this country.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.