Many millions of Indian graduates should be allowed to take white collar jobs from U.S. college graduates, says a coalition of top U.S. business leaders.

The U.S. India Strategic Partnership Forum is a spin-off of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. It is run by the current and former CEOs and presidents of Cisco, Boeing, Deloitte, Adobe, Caterpillar, Dell, FedEx, Medtronic, Marriott, PepsiCo, and other companies. The forum’s 20-page pitch says:

The US-India Strategic Partnership Forum (USISPF) is committed to creating the most powerful strategic partnership between the U.S. and India. Promoting bilateral trade is an important part of our work, but our mission reaches far beyond this. It is about business and government coming together in new ways to create meaningful opportunities that have the power to change the lives of citizens

Amid the corporate blurb, the group admits it wants to allow the free movement of Indian graduates from low-wage India into the high-wage U.S. economy, saying “USISPF’s Workforce Mobility Committee will … continue to make the case for the free flow of skilled labor in both countries.”

“That’s just a fancy way of saying unlimited immigration … [and] is a recipe for a political explosion,” said Mark Krikorian, director of the Center for Immigration Studies. He continued:

U.S. computer careers would become completely foreignized … [and] the middle class could well experience the kind of displacement that much of the [Midwest industrial] working class has felt, potentially with similar consequences, like opioid epidemics.

The group is led by former Cisco CEO John Chambers, and it met with India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi on October 21.

Chambers’ group is aided by several Washington operatives, including former ambassadors Tim Roemer, Richard Verma, Frank Wisner, and Susan Esserman Partner, former Pentagon chief William Cohen, as well as Henry Kissinger and Condoleezza Rice.

Chamber’s group promises to lobby U.S. and Indian legislators, saying:

USISPF aims to further [the] interests of both nations by engaging with Democrats and Republicans in the House and Senate along with the Parliamentarians in India. USISPF believes that our shared democratic values lie at the heart of the growing U.S.-India Strategic Partnership, and will lead through dynamic exchanges on the legislative side.

The group’s desire for Indian college graduate workers is presented as the fix to a claimed shortage of skilled graduates in the United States — despite plentiful evidence that American graduates are being sidelined and fired so that Indian graduates can take more U.S. jobs. The forum’s pitch says:

Trade is a two-way street. U.S. companies are major job creators in India. Likewise, it is important to recognize the contribution Indian companies make here in America. They have made significant moves to hire Americans announcing tens of thousands of new jobs in recent months. In addition to creating well-paid American jobs, Indian companies are addressing the STEM skills gap, and driving innovation across the US economy. These companies are truly deepening the U.S.-India relationship in part by leveraging high skilled visa programs that are widely recognized as benefiting the US economy. Visa holders bring skills that are not easily available, pay taxes, and help drive the US innovation economy. USISPF’s Workforce Mobility Committee will continue to champion the contributions these companies are making to communities across the US, and will continue to make the case for the free flow of skilled labor in both countries.

The group also says U.S. companies can work with Indian companies to cut U.S. healthcare costs — likely via the increased use of cheaper Indian nurses, therapists, managers, and doctors:

The landscape for this sector is shifting dynamically in both nations, with the governments focusing on improving accessibility and quality of care, while lowering costs. Without compromising on innovation, there is a need to explore new partnerships and business models.

Cheap Indian labor would be a massive windfall for U.S. investors. If U.S. healthcare companies could provide just 500,000 Indians for the U.S. healthcare sector, wages would decline, and investors would see a spike in stock prices.

Chamber’s team received a warm welcome from Modi, partly because the government wants to grow the nation’s economy by exporting graduates into the U.S.-India Outsourcing Economy. In February 2019, the Forsyth County News reported:

Ani Agnihotri, program chair of the USA-India Business Summit … said India has a massive and young population that could provide skilled, English-speaking workers ready to relocate “even at a seven-day notice” and said the majority of doctors in the United Kingdom and about 15 percent in America are of Indian descent.

“India has the youngest population in the world. About 25 percent of the population of India, which is 1.25 billion, is below the age of 25,” he said. “We will be the provider of the workforce of the world in about 15 years, after 2035.”

That outsourcing strategy is welcomed by U.S. investors who are now worried about a loss of Chinese imports and exports. The Indian strategy allows them to cut their U.S. payroll costs — and also helps Indians buy U.S. food, energy, services, and products from the growing network of Amazon, Walmart, and Apple stores in India.

India’s population of 20-something men is roughly 127 million. The population of 20-something women is roughly 113 million, for a total 20-something population of 240 million. That supply of labor is 11 times the United States’ 20-something population of 22 million.

Roughly 170 million Indians are enrolled in undergraduate or post-grad university courses, where the quality is extremely uneven, cheating is conventional, and nepotism is normal. But the output of more than 20 million graduates each year Chambers the prospect of importing at least 5 million graduates per year into the U.S. market.

In contrast, U.S. universities now supply U.S. businesses with just roughly 800,000 American graduates with skilled degrees in healthcare, business, engineering, software, science, math, and architecture.

However, the U.S. supply of labor has already been boosted by U.S. visa-worker programs, which keep a population of roughly 1.5 million foreign graduates — including around 800,000 Indians — in U.S. jobs.

In September, the growing Indian population in the United States held a rally for Modi in Texas, where many U.S. politicians applauded him.

The Indians population has grown in the United States, mainly because U.S. companies and Indian managers are importing Indian graduates via the visa worker programs.

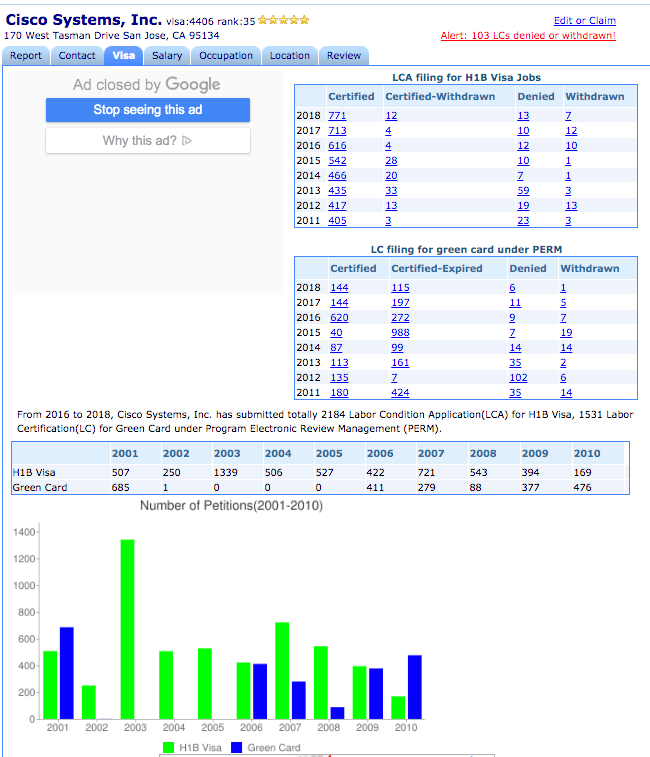

During his years at Cisco, Chambers encouraged and allowed Cisco managers to hire Indian graduates via the government-provided H-1B visa program. The policy pushed many Americans out of Cisco and has left many Indian managers throughout the company.

This workforce replacement has coincided with the discovery of significant technical problems in Cisco’s products. In March, Wired magazine reported:

The Cisco 1001-X series router doesn’t look much like the one you have in your home. It’s bigger and much more expensive, responsible for reliable connectivity at stock exchanges, corporate offices, your local mall, and so on. The devices play a pivotal role at institutions, in other words, including some that deal with hypersensitive information. Now, researchers are disclosing a remote attack that would potentially allow a hacker to take over any 1001-X router and compromise all the data and commands that flow through it.

…

The fact that the researchers have demonstrated a way to bypass [the security lock] indicates that it may be possible, with device-specific modifications, to defeat the Trust Anchor on hundreds of millions of Cisco units around the world. That includes everything from enterprise routers to network switches to firewalls. In practice, this means an attacker could use these techniques to fully compromise the networks these devices are on. Given Cisco’s ubiquity, the potential fallout would be enormous.

More than 80 percent of Cisco’s foreign workers come from India, according to MyVisaJobs.com:

India (1005); China (108); Canada (50); Mexico (23); Brazil (13); United Kingdom (13); Pakistan (10); Australia (9); Israel (9); Egypt (7)

These visa workers used a variety of different visa programs to get U.S jobs, according to the site:

H-1B (937); L-1 (313); F-1 (68); TN (8); E-3 (4); L-2 (4); H-4 (3); Parolee (2); Not in USA (1); J-2 (1)

In March, Cisco was awarded the “Padma Bhushan” award from the government of India,

Other business groups are trying to boost the flow of Indians graduates into the U.S-India Outsourcing Economy.

For example, the immigration director at a Koch-funded advocacy group told a House committee that legislators should allow an unlimited inflow of H-1B workers into the U.S. healthcare sector. “The [annual] cap [of 85,000 work visas] should be repealed altogether for the healthcare sector, as it is for the university and non-profit sector already,” Daniel Griswold, the director of trade and immigration issues at the Koch-funded Mercatus Center in Arlington, Va.

In 2018, U.S. healthcare companies sought to import 22,000 H-1B workers into healthcare jobs.

Currently, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, and Apple’s Tim Cook are supporting a push by Utah GOP Sen. Mike Lee to allow U.S. and Indian companies to recruit and reward many extra Indian workers. Lee’s bill offers Indians an increased allocation of green cards, up from roughly 10,000 cards per year to 60,000 cards per year.

Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin is blocking Lee’s S.386 plan. But Durbin wants to award Indian workers with up to 100,000 green cards per year if they snatch jobs from American graduates.

The bills by Lee and Durbin would also dramatically raise the incentives for Indian graduates to take sweatshop jobs in the United States via the uncapped B1, OPT, CPT, J-1, and TN visa programs. Those sweatshop jobs are valuable to the Indians because they serve as an on-ramp to the H-1B program, which allows employers to provide green cards to workers and their families.

Utah’s Lee has tried and failed to pass his S.386 giveaway bill four times via the fast-track Unanimous Consent process.

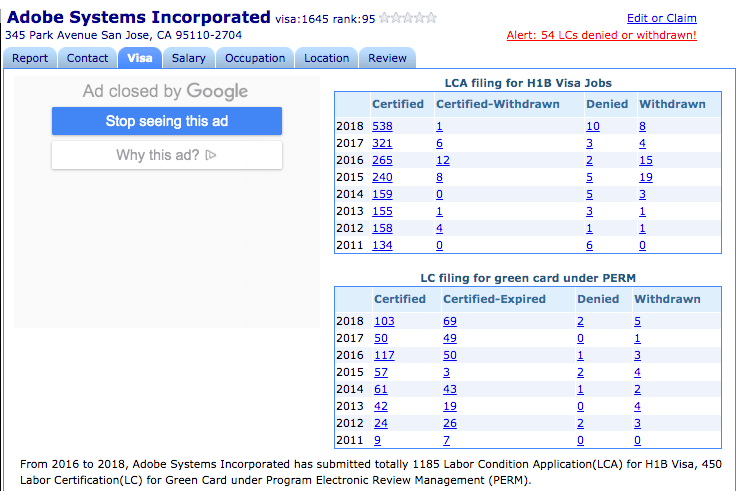

The leading technology executive in Utah — Shantanu Narayen, president of Adobe — is an Indian and a member of Chamber’s outsourcing advocacy group.

Adobe is also a significant user of Indian H-1Bs. In 2018, the company filed 583 “Labor Condition Applications” at the Department of Labor to get at least 538 H-1B visas — up from 321 LCAs in 2017. In 2019, Adobe asked for 469 LCAs for H-1B workers.

On October 22, Modi also announced he was meeting with former U.S. and European politicians working with the JP Morgan International Council, which is led by Tony Blair, the former U.K. prime minister. One of the attendees was banker Jamie Dimon, who also is a member of Chambers’ partnership forum.

The U.S.-India Outsourcing Economy

Roughly 800,000 Indian college graduate visa workers now hold a wide variety of U.S. jobs in technology, health care, accounting, and business. Moreover, these visa workers have helped to move more than one million additional U.S. jobs back to teams of graduates working in India.

This onshore/offshore process is described in a discrimination lawsuit against one of the Indian-owned outsourcing firms, Larson & Toubro Infotech.

The firm won a technology support contract from Iconix Brand Group Inc. in New York. The support was managed by one American employee of Larson & Toubro, according to the lawsuit filed by the D.C. firm of Kotchen & Low. The single American ran a New York team, which consisted of roughly eight Indians who likely arrived with H-1B work visas, the lawsuit says. But the single American also ran a team of 20 Indians in India, and he reported to two Indian managers in India. So the visa programs allowed the Indian company to take roughly 30 good jobs from U.S. white-collar workers with just eight visas, according to the lawsuit.

The lawsuit noted that “from 2013 to 2018, LTI received 9,785 new H-1B visas (or visa amendments) and almost 200 new L-1 visas (or visa amendments) – far more positions than could actually exist given that LTI only employs about 7,500 employees in the U.S.” The surplus of visa workers allows the company to sideline American job seekers and instead hire lower-wage Indian visa workers.

The use of cheaper Indian labor created payroll savings for Iconix and profits for Larson. In turn, those profits boosted the company’s stock values for U.S. investors, including the Vanguard International Stock Index.

This outsourcing economy has helped to deny jobs to millions of American graduates and to cut salaries earned by American graduates, both young and old, just as blue-collar wages crashed when U.S. investors used free-trade rules to transfer factories workers into China. The outsourcing pressure helps to explain why white-collar salaries are growing slower than wages for blue-collar jobs in President Donald Trump’s economy.

In fact, the U.S.-India Outsourcing Economy has grown so much that it has clogged the U.S. immigration system. The clog is forcing many of the contract workers to wait more than a decade to get the green cards they were promised by employers in exchange for taking Americans’ jobs.

That long wait helps the companies by keeping their many contract workers stuck in their jobs, tied to their employers — often at substandard wages.

But the long wait also makes it difficult for outsourcing companies to recruit more Indian workers. After all, fewer Indians will sign up for the outsourcing industry if the companies cannot deliver the fast-track green cards.

That green card clog is also a huge problem for India’s government because its entire economic strategy is built around the export of workers into foreign economies.

Many high-tech companies and investors want India’s government to help them get into Indian’s growing marketplace, especially as the trade war with China heats up. So Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, and Apple’s Tim Cook, and many other corporations are working with GOP Sen. Mike Lee to unclog the outsourcing and the recruiting process by removing the “country caps” that delay the award of green cards to Indian visa workers.

The pipeline of Indian workers into the United States is built on the H-1B program.

The H-1B program is uncapped for non-profit employers, but companies can get 85,000 new H-1B workers into the United States per year. Each H-1B worker must go home after six years, so capping the companies’ workforce of H-1B workers at around roughly 480,000 workers. That workforce provides companies with roughly equal to one Indian worker for every nine Americans who graduate with skilled degrees each year.

But that resident H-1B workforce is just a start.

In 1990, Congress decided to let workers in the H-1B program — and in the smaller, lesser-known L-1 program — to apply for green cards. This 1990 decision created the huge citizenship prize, which is pulling many Indians into the H-1B program and ensuring they will brave low wages, tough conditions, and often illegal working conditions to win the prize.

Up to 300,000 additional Indians are working while waiting for green cards, long after their six-year H-1B visa expired.

Few Americans appreciate the huge value of green cards and citizenship. Yet Congress allows U.S. and Indian investors to freely trade this citizenship prize to 10,000 Indian graduates every year in exchange for a decade or more of profitable work. Of course, millions of foreigners will accept that giveaway deal — and millions of foreigners will feel a moral duty to shove Americans out of their jobs, homes, and careers so they can grab the fantastic prize for their spouses, children, grandchildren and fellow nationals.

Lee’s bill will allow companies to make that barter with roughly 60,000 Indian graduates per year, up from 10,000 per year under current “country cap” rules. The 60,000 cards a year would reduce the wait for green cards down to several years, so encouraging more Indians to join the H-1B program.

But the federal government has quietly created many other programs that allow foreigners to easily take jobs in the United States, regardless of whether Americans want those jobs.

Federal law allows an unlimited number of Indians to get jobs in the United States via the B1 visa for foreign workers, the TN program for businesses based in Canada and Mexico, as well as the uncapped “Optional Practical Training” and “Curricular Practical Training” work permit programs for foreign students and graduates at U.S. colleges.

The mass of OPT and CPT workers in the United States have their own sweatshop economy, where they crowd into shared housing while they work as temporary contract workers for the middlemen subcontractors, which are quietly hired by brand-name Fortune 500 firms. But many Indian graduates do not want to join the OPT sweatshop economy — unless they can also get promoted into the L-1 or H-1B program to get green cards.

So if Sen. Lee or Sen. Durbin unclogs the green card pipeline, more Indian graduates will flood into the feeder pipelines created by the B-1, TN, OPT, and CPT programs so they can get green cards after being promoted into the main L-1 and H-1B pipelines.

Current data shows roughly 800,000 Indians work in the United States — including many who are working-and-waiting for more than 15 years to get one of the 10,000 green cards issued to Indians each year.

If companies can offer more green cards each year, then more Indians will get into the pipeline. In turn, that pressure will push more young and old U.S graduates out of jobs, onto the streets — and likely into the voting booths.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.