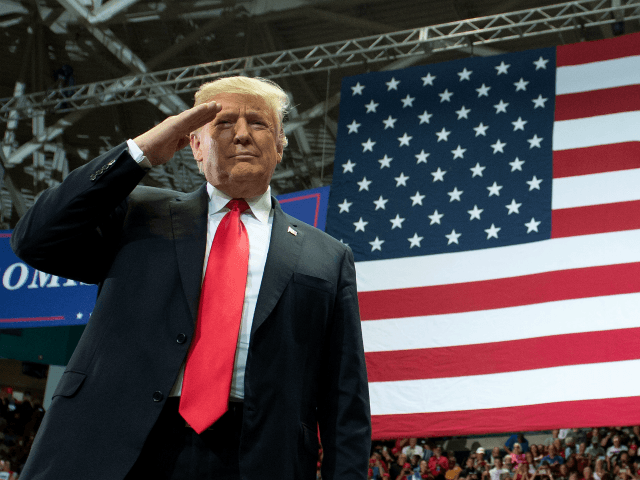

President Donald Trump is considering an executive order restricting birthright citizenship for illegal aliens’ children, which could create a Supreme Court test case that could end that misinterpretation of the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment, either through presidential action or through legislation.

The original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause promises birthright citizenship to people born on U.S. soil only if they are not citizens of a foreign nation, giving Congress the option of denying citizenship to the children of foreigners. Critics would be wise to hold off criticizing President Trump’s planned executive order focusing on illegal aliens until they see what is in it.

Everyone is suddenly talking about the first clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which provides, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Several pivotal moments in American history shine light on the meaning of those words.

The Supreme Court decided its most infamous case, Dred Scott, in 1857. John Sanford owned Scott as a piece of property. The Court held that black people were not U.S. citizens, and thus federal courts lacked jurisdiction to hear Scott’s lawsuit challenging his status as a slave. Dred Scott marked a turning point on the issue of slavery, and four years afterward America descended into the Civil War.

The movie Lincoln recounts how, as he was leading the Union to victory in the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln pushed the Thirteenth Amendment through Congress to end slavery. It was a Republican-led effort, in which Lincoln the Republican peeled off just barely enough Democrats to get the requisite two-thirds in Congress to send the proposed amendment to the states for ratification.

Congress proposed the Thirteenth Amendment to the states on January 31, 1865. On December 6, 1865, the necessary three-fourths of states voted to ratify the amendment, adding its words to the Constitution. Section 2 of that amendment authorized Congress to pass new legislation consistent with ending slavery.

Lawmakers invoked that authority just months after ratification, passing the Civil Rights Act of 1866 on April 9 of that year. That statute included a citizenship clause that provided, “All persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.”

Some members of Congress like Rep. John Bingham (R-OH), who supported rights for newly freed blacks, nonetheless opposed the Civil Rights Act, explaining that they believed such legislation went beyond the authority granted by Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment to pass laws enforcing the end of slavery.

They argued instead that a new constitutional amendment was needed, and immediately drafted and pushed for congressional debate of a proposed Fourteenth Amendment. Key provisions from the Civil Rights Act were rewritten as part of the new draft amendment, including the Civil Rights Act’s citizenship clause, but changing the words “and not subject to any foreign power” to “and subject to the jurisdiction [of the United States].”

The purpose of the Citizenship Clause was to supersede Dred Scott, securing citizenship for black Americans. The current debate is over how broadly Congress and the ratifying states acted when they amended the Constitution to undo Dred Scott’s denial of citizenship.

Article I, Section 8, Clause 4 of the Constitution gives Congress plenary authority over immigration and naturalization, subject only to the additional restriction now imposed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

But the Citizenship Clause is only a floor that Congress cannot go below. Congress can be as generous as it wants to concerning citizenship above that floor; lawmakers could pass a law granting citizenship to every person who ever enters this nation, or even to all 7 billion people on the planet.

What exactly is the floor decreed by the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause?

The entire debate over birth citizenship turns on a single question: Did Congress change the meaning of “not subject to any foreign power” in the Civil Rights Act when it substituted “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” in the Fourteenth Amendment, or was Congress merely using alternative words that meant the same thing?

The Congressional Globe – which was the authoritative source for congressional debates in the 1860s – only provides limited material, but enough to conclude that Congress was retaining the original meaning. There is no widespread discussion on the House or Senate floors to suggest that lawmakers thought they were adopting a different standard in the constitutional amendment than they had approved just months ago for the Civil Rights Act.

To the contrary, Sen. Lyman Trumbull (R-IL) – who was instrumental in shaping the language and getting the amendment through the Senate – said during debates that “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States meant subject to its “complete” jurisdiction. In other words: “Not owing allegiance to anybody else.”

Likewise, Sen. Jacob Howard (R-MI), who introduced the language of the amendment’s jurisdictional language on the floor of the Senate, insisted that the term should be construed to mean “a full and complete jurisdiction,” and “the same jurisdiction in extent and quality as applies to every citizen of the United States now” (meaning now that the Civil Rights Act had been passed), except for Native Americans.

On that note, the Senate rejected a proposed change by Sen. James Doolittle (R-WI) to add back words to exclude “Indians not taxed,” to mirror the Civil Rights Act. But that idea to add the exclusion was rejected, because lawmakers concluded that Native Americans on reservations, even though on American soil – and thus subject to the jurisdiction of U.S. laws – where not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States in the political sense that the amendment used the term, and thus that the words about excluding them could be cut without changing the amendment’s meaning.

The Fourteenth Amendment was voted out of Congress and sent to the states on June 13, 1866. It was ratified by the states two years later on July 9, 1868.

The first Supreme Court case discussing the Citizenship Clause was the Slaughter-House Cases of 1873, a mere five years later. Although Slaughter-House is routinely criticized today for its confusing ruling on the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause – a separate provision that is completely irrelevant to birthright citizenship, so does not warrant further discussion here – the Court did make a clear statement about the Citizenship Clause.

The Court in Slaughter-House explained, “the phrase ‘subject to the jurisdiction’ was intended to exclude from [birthright citizenship] children of … citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States.” That reading is completely consistent with the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

The greatest constitutional scholar of the time, Thomas Cooley, agreed in his famous 1880 book, The General Principles of Constitutional Law. He wrote that “subject to the jurisdiction” “meant full and complete jurisdiction to which citizens are generally subject, and not any qualified and partial jurisdiction, such as may consist with allegiance to some other government.”

The Supreme Court directly ruled on the Citizenship Clause a decade after Slaughter-House in the 1884 case Elk v. Wilkins, where a Native American who was born on a reservation moved to Nebraska and attempted to register to vote. When he was denied voter registration because he was not a U.S. citizen, he filed suit.

The Court held that the Citizenship Clause did not guarantee John Elk birthright citizenship, because “subject to the jurisdiction” means “not merely subject in some respect or degree to the jurisdiction of the United States, but completely subject to their political jurisdiction, and owing them direct and immediate allegiance.”

“Indian tribes, being within the territorial limits of the United States, were not, strictly speaking, foreign states,” the Court continued, since U.S. law had jurisdiction reach there. Nonetheless, as their members were expected to owe part of their political allegiance to the tribes, “they were alien nations, distinct political communities,” and thus not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States for purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court elaborated that although John Elk and other Native Americans on reservations were:

within the territorial limits of the United States, members of, and owing immediate allegiance to, one of the Indian tribes (an alien though dependent power), although in a geographical sense born in the United States, are no more “born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” within the meaning of the first section of the fourteenth amendment, than the children of subjects of any foreign government born within the domain of that government, or the children born within the United States, of ambassadors or other public ministers of foreign nations.

In 1898, the Court might have departed from this original public meaning in United States v. Wong Kim Ark. The Court held, “a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who at the time of his birth were subjects of the emperor of China, but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States,” was, as a consequence of being born in the United States, a citizen of the United States under the Citizenship Clause.

Wong Kim Ark was the final Supreme Court case speaking directly to this issue. But even if the Court got that one wrong, it has no bearing on President Trump’s executive action. Wong’s parents were lawful permanent residents of the United States who had severed all ties and allegiance to China. President Trump is dealing here with illegal aliens only, not legal aliens. The Supreme Court would not need to overrule Wong Kim Ark to rule in favor of President Trump’s action.

The only possible Supreme Court impediment is a footnote in one modern case, Plyler v. Doe. Written by arch-liberal Justice William Brennan in 1982, Plyler involved a Texas law denying free public-school education to the children of illegal aliens. The plaintiffs challenged that law under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which does not allow a state to deny “equal protection of the laws” to any person “within its jurisdiction.” (Note that “within its jurisdiction” is different wording than “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” in the Citizenship Clause.)

In footnote 10 of that decision, the stridently liberal Brennan inserted that “no plausible distinction with respect to Fourteenth Amendment ‘jurisdiction’ can be drawn between resident aliens whose entry into the United States was lawful, and resident aliens whose entry was unlawful.”

Plyler was a 5-4 liberal decision. Not only did conservatives like Justice William Rehnquist dissent, but so did all the moderates, such as Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Modern conservative lawyers have looked for an opportunity to overrule Plyler and its footnote 10 for years, and now they may have an opportunity to do so.

Because the Citizenship Clause is a different Fourteenth Amendment provision than the Equal Protection Clause, it is also possible that the Court could rule in favor of President Trump without revisiting Plyler at all.

President Trump’s imminent order could set up a test case both of the meaning of the Citizenship Clause, and critics should refrain from opining until they see what is in the expected executive order, lest they risk embarrassment.

Some federal welfare programs are restricted for noncitizens. Foreigners are not eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or various other programs, even if they are in the U.S. legally, unless they have been here for many years. Illegal aliens are excluded from even more programs.

President Trump could order the relevant departments and agencies not to enroll children born to illegal aliens into these programs, contending that they should not be regarded as U.S. citizens. That would likely spark a legal challenge, which would eventually reach the Supreme Court.

One unexpected issue here is the separation of powers question: How much can a president do under the Constitution and current federal law to address birthright citizenship, versus what matters need to be left to Congress? There is no question that only Congress can literally change a statute, but how much can a president do without new action by Congress?

The strength of the legal challenge will turn in part over what precisely the executive order commands, and in another part on this distinction between legislative and executive power. One would think that President Trump’s opponents would have learned by now that they risk embarrassment when they cavalierly say that a president’s actions are illegal; in Trump v. Hawaii, the Court upheld President Trump’s travel ban as being authorized by Congress’s current law, despite talking heads’ smug assurances that the travel ban was blatantly illegal.

President Trump has at least two routes to victory through a legal fight. It must be noted for both that a legal challenge to an executive order issued in November 2018 would almost certainly not make it all the way to petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court until after the cutoff in mid-January 2020 for cases to be decided before the presidential election, so this issue will likely still be pending when Americans go to the polls in November 2020 to vote for president.

The first route to victory is that the Supreme Court could hold that the specific provisions of the executive order are authorized under current statute. If so, President Trump wins outright.

The second is that the Court could hold that one or more of those provisions require congressional action, but could signal that the Constitution permits such changes. If so, there would be a massive push to tweak current statute. The American people will have been debating this issue for two full years by that time, and would by 2021 be educated by the Supreme Court’s final decision as well. This could lay the groundwork, such that the same political momentum that would secure a second term for President Trump could also secure the votes to change the relevant provision of Congress’s Immigration and Nationality Act.

All this would be happening as the president continues to appoint federal judges who believe the Constitution must be interpreted according to its original public meaning. President Trump may well have a third Supreme Court vacancy before this matter is argued before the justices, securing even more a reliable originalist majority on the Court.

President Trump has elevated a national discussion on an extraordinarily important issue that has been building for decades. He appears to be shaping the very battlefield on which he will fight, on a matter that tens of millions of voters care about deeply.

Ken Klukowski is senior legal editor for Breitbart News. Follow him on Twitter @kenklukowski.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.