Immigrants are assimilating to American society at a much slower rate than in prior decades, says a 495-page report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

The evidence shows a “slowing rate of wage convergence for immigrants admitted after 1979,” said the report, titled “The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration.”

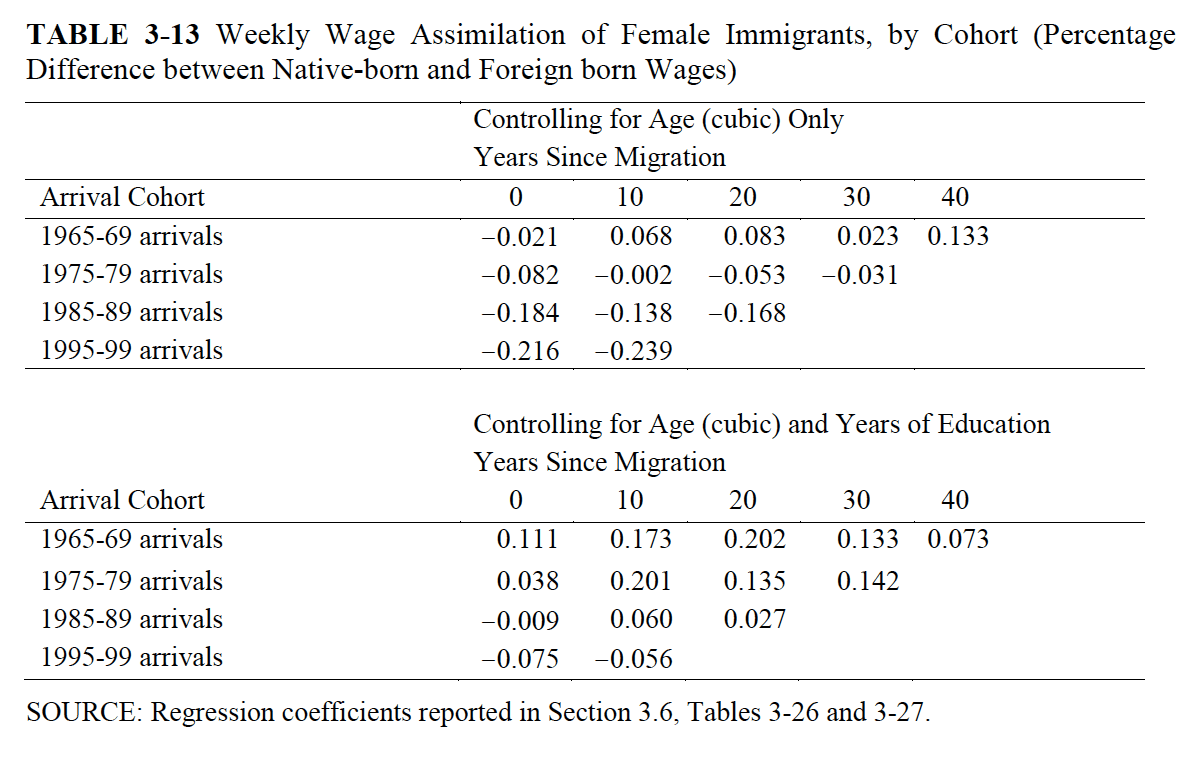

“These overall conclusions hold after controlling for immigrants’ educational attainment,” the report says. It is due to be released Sept. 22, in time for the 2016 election.

For example, immigrants, legal and illegal, who arrived between 1965 and 1969 halved the wage gap with native-born Americans from -0.25 to -0.120 in 10 years and effectively eliminated the gap by after 20 years, the report says.

In contrast, the immigrants who arrived between 1995 and 1999 have barely made any progress in closing the average wage-gap with native-born Americans, the report shows in Table 3-12.

When education is factored in, the 1990s immigrants have halved the wage cap in 10 years, while the 1960s immigrants reduced their wage gap by down to one-sixth in 10 years.

The reality may be even worse than is shown by the earnings data because a large number of less-proficient migrants eventually return home, so removing themselves from the data, the report says.

“Immigrants who stay in the United States earn more than those who decide to leave; therefore, estimates of the rate of wage convergence derived from a census or sample of immigrants who remain in the United States are biased upwards,” the report said while summarizing one outside study.

Part of the economic problem is that migrants aren’t learning English as fast as their predecessors. “The general result holds that immigrants who arrived during the late 1980s and 1990s are slower in accumulating language skills than those who arrived in the late 1970s,” the report says.

The likely cause is the surge in Latino immigration, the report notes.

The relative slowdown of language assimilation may again be partly explained by high rates of immigration from Mexico during the 1990s. Lazear (2007) found that Mexicans start below immigrants from other countries in terms of English language fluency and never catch up; in general, non-Hispanics were more fluent than Hispanics at all times after arrival in the United States. One possible explanation, articulated by Borjas (2014b, p. 35), is that “immigrants who enter the country and find a large welcoming ethnic enclave have much less incentive to engage in these types of investments since they will find a large market for their pre-existing skills.”

In turn, that continuing wage gap spikes immigrants’ use of welfare, especially among the children and grandchildren of immigrants, the report says.

Based on 2011-2013 March CPS data, [the report] reveals that, between ages 20 and 60, the third-plus generation receives more means-tested antipoverty program benefits than either the first or second generations. Among the underlying factors are that recent arrivals do not qualify for many of these programs initially, and the second generation has a slightly more favorable socioeconomic status than does the third-plus generation.

Immigrants’ greater use of welfare and income-support programs has been repeatedly tracked and publicized.

That increase, however, is partly caused by the federal government decision to offer more aid Americans and immigrants to help offset the $500 billion in annual wage-reduction that is caused by immigration.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.