The once venerable Lancet medical journal has become ever more fixated on race and gender, sidelining its earlier commitment to medicine.

In its most recent issue, the Lancet warns that “despite decades of discussion of diversity and inclusion, Black people continue to be severely under-represented in academia.”

The “complete absence of Black female progression” at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM), for instance, an institute deeply steeped in work on Black people, manifests “exclusionary violence.”

What is needed is “a specific focus on anti-Blackness, including the introduction of a dedicated principle to address it,” the journal asserts.

The Lancet points to the Race Equality Charter (REC) as a sign of hope, noting that it gives “bronze and silver awards in racial equality” and is “therefore important.”

“The failure of the revised REC to promote more specific targeting of anti-Blackness,” however, “misses an important opportunity,” the journal laments.

The Lancet goes on to ask to what degree “have underlying higher education institutions’ cultures of anti-Blackness hampered uptake of the recommendations addressing this problem?”

The journal’s digression into racism and “anti-Blackness” is just the latest in an ongoing pattern of obsession with race and gender as part of its stated embrace of the “progessive agenda.”

The Lancet has also denounced “medical racism” in the United States as part of alleged “structural violence” present in the country.

“While much public health research has shown that racism is a fundamental determinant of health outcomes and disparities, racist policy and practice have also been integral to the historical formation of the medical academy in the USA,” the journal declared in 2020.

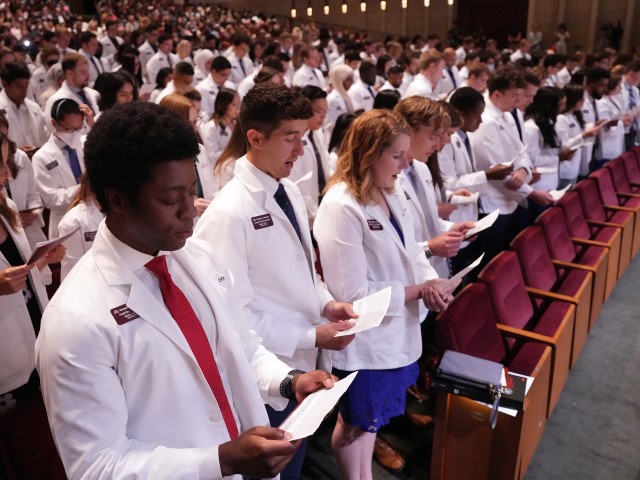

“Like the history of US policing, the history of medicine and health care in the USA is marked by racial injustice and myriad forms of violence: unequal access to health care, the segregation of medical facilities, and the exclusion of African Americans from medical education are some of the most obvious examples,” the article stated.

“These, together with inequalities in housing, employment opportunities, wealth, and social service provision, produce disproportionate health disparities by race,” it continued. “The health community needs to confront these painful histories of structural violence to develop more effective anti-racist and benevolent public health responses to entrenched health inequalities, the COVID-19 pandemic, and future pandemics.”

That same year, the Lancet went further still, publishing a tendentious book review asserting that “white Americans continue to mobilise to maintain or extend the exclusive advantages whiteness offers those who can become white.”

The Lancet chose Rhea W. Boyd, a Minority Health Policy Fellow at Harvard’s School of Public Health, to review a 2019 book called Dying of Whiteness by Jonathan Metzl, whose thesis is that “right-wing backlash policies have mortal consequences — even for the white voters they promise to help.”

In order to “maintain an imagined place atop a racial hierarchy,” white Americans who harbor “racial resentment” support policies that seem to limit the freedoms or resources available to non-whites, even though such decisions threaten their own wellbeing as well, Metzl argued.

In her review, Boyd expressed fundamental agreement with Metzl’s contentions, yet asserted that he is too soft on whites by attributing whites’ self-destructive political actions to “racial resentment,” which “erases white agency through emotional euphemism.”

The simple fact is that “despair isn’t killing white America, the armed defence of whiteness is,” she wrote. Thus, death “is the inevitable consequence of the full realisation of structural racism and the exclusive rights and resources it offers those who can become white.”

In reality, Boyd concluded, the only real solution “is to eliminate whiteness all together.”