CARACAS, Venezuela – It certainly goes without saying that the past weeks have been tumultuous and atypical for all of us, and lives have been turned upside down as a result of Coronavirus — Venezuela being no exception.

For the past month, Nicolás Maduro’s regime has placed Venezuela under a fierce quarantine that – alongside the ongoing humanitarian crisis and an already destroyed economy – has severely exacerbated every woe and tribulation that we had been facing as a consequence of the utter collapse that Socialism has unleashed upon this country. Blackouts, barely functional public utilities, food shortages, and now even gasoline — the only thing we produce in this country is pretty much an odyssey to obtain.

Strangely, after almost an entire decade of socialist collapse, we’re kinda used to this rodeo of long lines, dwindling supplies, and the anxiety spawned from such circumstances, unfazed even — which is why I say that my daily loop hasn’t changed that much during this first month of “Social Quarantine.”

The first days following the announcement of the first confirmed case of coronavirus in Venezuela were filled with abject panic; crowds of customers flocking supermarkets and pharmacies desperate to get their hands on whatever supplies and groceries they could get and afford, just like in past times of heated protests.

Huge lines aren’t a new phenomenon to us. I would go as far as to say that they’ve regrettably have become part of our idiosyncrasy – another consequence of Hugo Chávez’s Socialism of the XXI Century. After years upon years of lines and queues, one does become desensitized to them. The way I’ve been palliating them is through carefully programming our meals days in advance and restocking on what we need through single weekly supermarket trips so as to minimize the amount of time spent on these often long lines — waiting outside before said supermarket opens so I can be among the first to enter seems to be the most optimal way to lessen the amount of time invested.

Early bird gets the worm or, in my case, eggs.

Waiting on a supermarket line in Caracas, Venezuela, during the coronavirus pandemic of 2020. (Christian K. Caruzo)

Thankfully, I’ve been able to secure beef and poultry (which have once again become scarce) through some contacts, but it’s come at a steep price increase due to the low supplies, high demand, and drastic gasoline shortages. I am always thankful to God because meat is something that the majority of the country can’t afford to obtain, and a mandatory quarantine can no longer hide the hunger of those more impoverished.

Our currency, or what’s left of it, has plummeted in value so hard over these past hours that in my latest supermarket trip I saw a few people waiting for the exchange rate to go a little higher before checking out just to get the most bang for their greenbacks. The volatility has been so drastic that by the time you’re ready to check out, the exchange rate can be drastically different than what it was when you started to queue up outside the supermarket.

Maduro’s threats of reinstating the draconian price controls and regulations that asphyxiated our economy for years is looming on the horizon. I honestly do not look forward to once again being able to only purchase X amount of Y per week, the fingerprint scanners, and only being able to buy certain things on specific days based on the last number of my Venezuelan ID card (which ends in 8, so that means Fridays and Sundays for me).

I’m too worn and tired to go through all that once more, in all honesty.

Caracas, a city that’s often riddled with the chaos of traffic, feels as close to a ghost town as it can get. Police checkpoints scattered all over the place ensure that only those that absolutely need to go outside are the ones transiting through the near barren streets of this city. I wasn’t even able to attend church on the 31st of March, the second anniversary of my mother’s passing. Wearing a mask to go outside is mandatory; thankfully, I managed to find a handful among my mother’s supplies.

Not everyone has the economic resources to simply stock up and hunker down. Many in this country can’t even properly feed their families and have to live day by day. In light of this, the regime is testing a harsher quarantine, enforced by the feared FAES Special Action Force.

The cacophony of car horns and other noises has been absent for over a month now, and the usual laughs and cheers of the children that play outside the building next to my bedroom are nowhere to be heard; it makes up for some quiet afternoons, I suppose.

The absolute destruction of our health system is not a secret to the world, and that adds fuel to the collective fear amidst this pandemic, for we’re ill-prepared to deal with this virus should it get out of hand. Am I distrustful of whatever is left of our health system? Yeah, considering what my mother had to go through during the last years of her life, an open wound for me, even after two years.

While there are official statistics of infected, recovered, and deceased, one finds them hard to believe in when it’s told by the same people that have lied countless times in the past and have done everything possible to perpetuate themselves in power — not to mention that twisting and obfuscating numbers is something they’re very good at.

Another issue is that if you dare openly question or dispute the veracity of the regime’s statistics, then you best be ready to face the consequences. Fear and censorship are weapons they’ve quite proficient with.

Over the past days I’ve faintly heard a voice through a megaphone in the distance, which reminds us that “it’s not easy, but we must follow the government’s recommendations.”

Earlier this week, we had a visitation from the regime’s health officials to this area, where a doctor from the Cuban Regime and her Venezuelan colleague (whose garb was embroidered with the ever so prevalent iconography of Hugo Chávez’s eyes) conducted a quasi-mandatory poll among the inhabitants of this apartment building, asking for our basic information and if we’re sick or not — that’s the full extent of the testing they’ve done on this building so far.

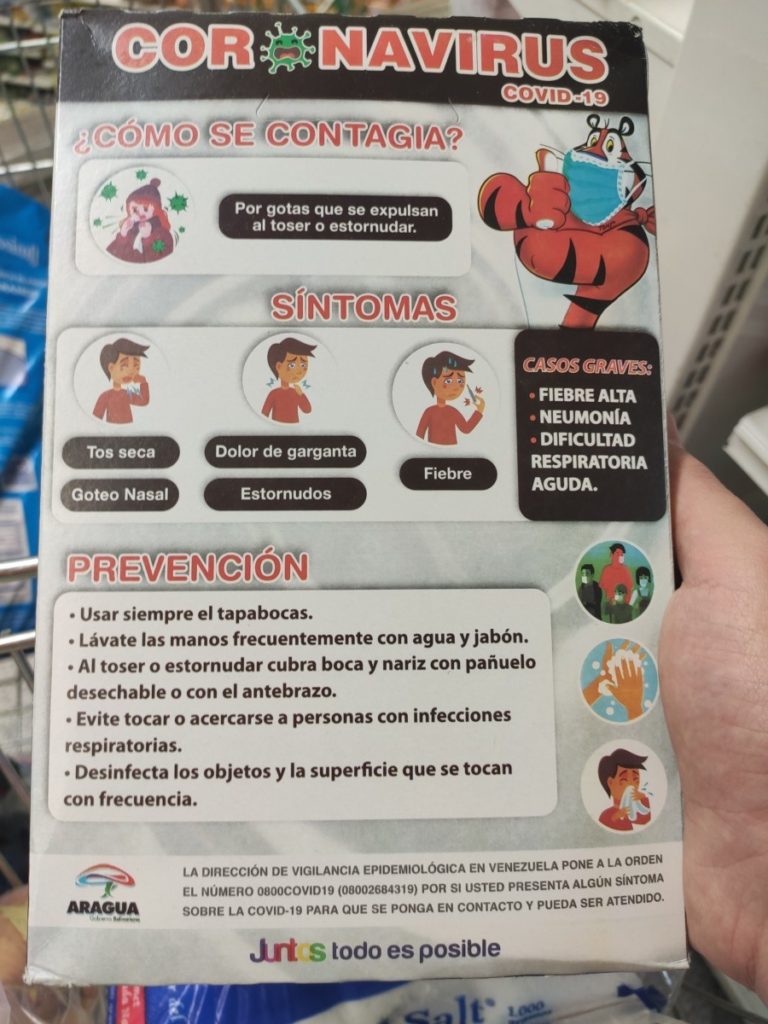

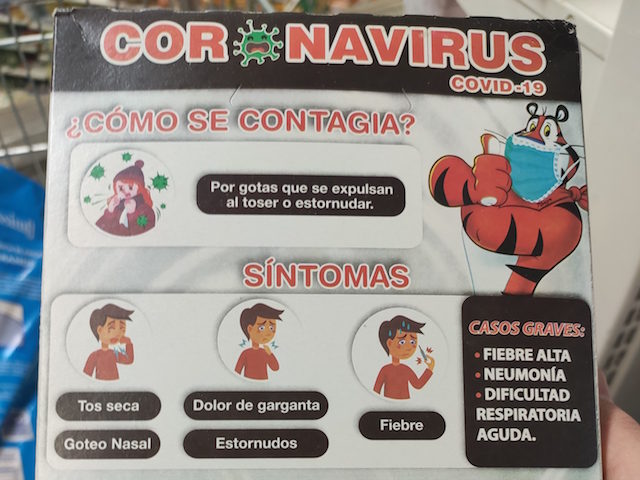

The back of a non-Kellogg-approved chocolate Frosted Flakes box featuring coronavirus tips and Tony the Tiger. Christian K. Caruzo.

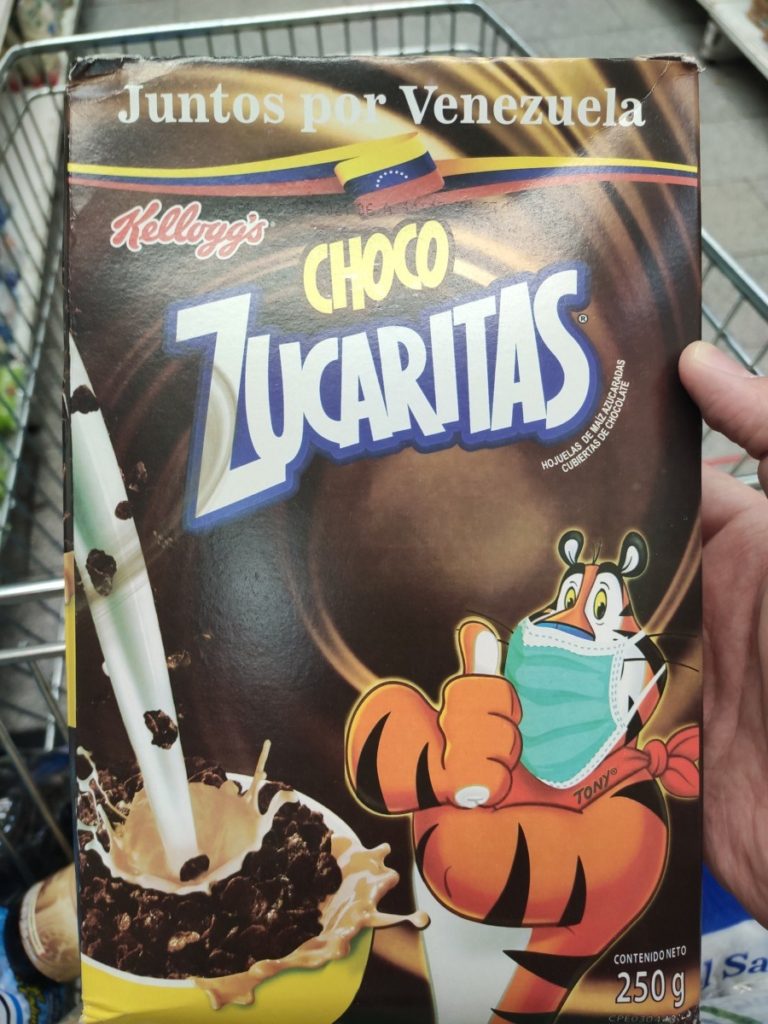

Chocolate frosted flakes box with coronavirus branding in Caracas, Venezuela. Nicolás Maduro seized the city’s Kellogg plant in 2018 after the company left the country and manufactures “Kellogg’s” cereals with no regard to intellectual property law. The box also features a Venezuelan flag and the slogan “together for Venezuela.” (Christian K. Caruzo)

Gasoline shortages have become so dire that spending hours, even days, waiting for it is the norm. In some places, there are specific lists of people that are allowed to refuel (namely, health and security employees) and told when.

As with all woes and tribulations that are spawned as a result of Socialism’s inevitable collapse, these drastic gasoline shortages have paved the way for even more blatant corruption. The guy that delivers my off-market frozen meat supplies tells me that the Bolivarian National Guard is selling oil for his motorbike at $1 per liter.

Protests continue to erupt across the country, but you’ll never know about them if you only consume the regime’s media. If you go by what they show, then you’ll find a country that’s happily and peacefully following Maduro’s call for social distancing and quarantine – where no one is missing anything, be it food, water, or medicine.

At any given moment, they’re either congratulating themselves for what they proclaim has been an “excellent job” or they’re taking jabs at other (capitalist) countries and how much of a bad job they’re doing, or how indolent they’ve been with their citizens (unlike the regime, which gives you “Love and Fatherland”).

America and Donald Trump are the number one recipients of said attacks by far, as if all of this was a competition of some sorts.

They also constantly remind you to take precautions, such as washing your hands often — to which I have to ask: With what water?

Our water rations have been most erratic these past weeks. Sometimes we’ve gotten 72 hours of water per week, sometimes less.

This rapidly has become an exercise in how much Maduro’s regime can openly get away with. The quarantine has been extended until mid-May. I don’t have my hopes up and expect Maduro to extend it past that day. Regardless, trying times are upon us here in Venezuela once this pandemic passes, because Socialism has already obliterated everything, and now we don’t even have gasoline.

Our lives have been reduced to a minimum and there’s so much I want and need to do but am unable to right now – heck, I can’t even leave this city right now. All I can do is take whatever precautions I can take to ensure the continued safety of my brother and myself.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.