America First—Finally

Much good can come out of World War V (“V” for “Virus,” in the coinage of Silicon Valley techie Balaji Srinivasan).

Yes, we will mourn the loss of life, yes, we will regret the personal and social disruption, and yes, we will have to work hard to restore our economic vitality. And we’ll have to work even harder to restore a proper sense of justice in this country, where the heroes of World War V—the “thin white line,” as well as others who fought to save us—receive a larger share of the rewards and benefits than they have heretofore.

We can do all these things, and more, if we follow the right vision and the right leadership. Indeed, history shows that we can come back stronger than ever—but only if we make the right moves.

For instance, we can start by moving to reclaim our health supply chains from their current dependence—that is, their end points in the People’s Republic of China. It was foolish, in the extreme, for past White Houses and Congresses to let American health companies outsource their production to China. And yet that’s exactly what happened, while Washington, DC, was focused on various Middle Eastern follies.

As a result, today, the U.S. makes pitifully little of what it truly needs—and that’s why we are confronted with humiliating headlines such as this, seen in the March 13 New York Times: “The World Needs Masks. China Makes Them—But Has Been Hoarding Them.” As the article detailed:

China made half the world’s masks before the coronavirus emerged there, and it has expanded production nearly 12-fold since then. But it has claimed mask factory output for itself. Purchases and donations also brought China a big chunk of the world’s supply from elsewhere.

The Times is too polite to come out and say so, but it seems obvious that the Chinese are trying to corner the market on protective face masks—leaving us to wonder why.

Yet now finally, after 30 years of globalist sleepwalking under both Democrats and Republicans, America is starting to wake up. And two of the leading Wide Awakes are Sen. Tom Cotton, Republican of Arkansas, and Rep. Mike Gallagher, Republican of Wisconsin; they have jointly put forth a bill in Congress: The Protecting our Pharmaceutical Supply Chain from China Act.

On March 25, Cotton and Gallagher published an op-ed in which they declared, “Our bill would require federal entities like the Department of Defense, VA hospitals, Medicare and Medicaid to cut off purchases of drugs with Chinese ingredients no later than 2025”—with the idea being that if those huge purchasers of medicines phased out their China purchases, the rest of the U.S. market would follow. In other words, American would independent of China, the country whose propaganda ministry recently crowed that we would “sink into the hell of the novel coronavirus.” In other words, Red China is exactly the sort of country we should not be relying on—for anything.

Still, the Cotton-Gallagher legislation is so upsetting to the globalist order that we should expect half the lobbyists in D.C. to oppose the bill. And yet the problem of our dependence on Big Panda is so severe that it’s likely that the goals of Cotton and Gallagher will be realized, one way or another, soon enough.

To be sure, from the point of view of a well-fed incumbent politician, it’s certainly nice to be funded and lunched by lobbyists and PACs working for globalist clients—and yet for the individual pol, it’s actually nicer to get re-elected. And that suggests movement in the direction pointed to by Cotton and Gallagher. That is, in light of the gathering crises over both corona and China, few politicians will wish to be seen as in the pocket of either the corporate outsourcers or of the Chinese.

According to Cotton and Gallagher, the problem is this:

Today, most active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used for drugs in the United States are made in China, including 95% of U.S. imports of ibuprofen, 70% of acetaminophen, and 40-45% of penicillin.

Of this litany of outsourced health necessities, the most poignant is penicillin. It was, after all, penicillin that helped us win World War Two. So if we see the Good War as the still-abiding moral heart of the modern-day worker-soldier-first-responder coalition—and we rightly should—then we must study our successes in World War Two, seeking to emulate them whenever possible.

Penicillin

Many people know that penicillin notatum was discovered accidentally, back in 1928, by a British doctor and bacteriologist, Alexander Fleming. It seems that Fleming had absent-mindedly left a piece of bread out in the open, where it grew moldy and thereby contaminated one of his laboratory’s petri dishes. And yet fortunately, Fleming was alert enough to notice that the bread-mold was killing the bacteria around it. As Fleming later wrote:

When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I guess that was exactly what I did.

Yet the story of penicillin is far more complicated than just a single serendipity of science. Fleming published his findings in 1929, and spent the next half-decade trying to produce penicillin on a larger scale. Yet he was disappointed to realize such production was arduously slow. And so, by 1935, unable to find research help, he had mostly given up on his effort to ramp up production.

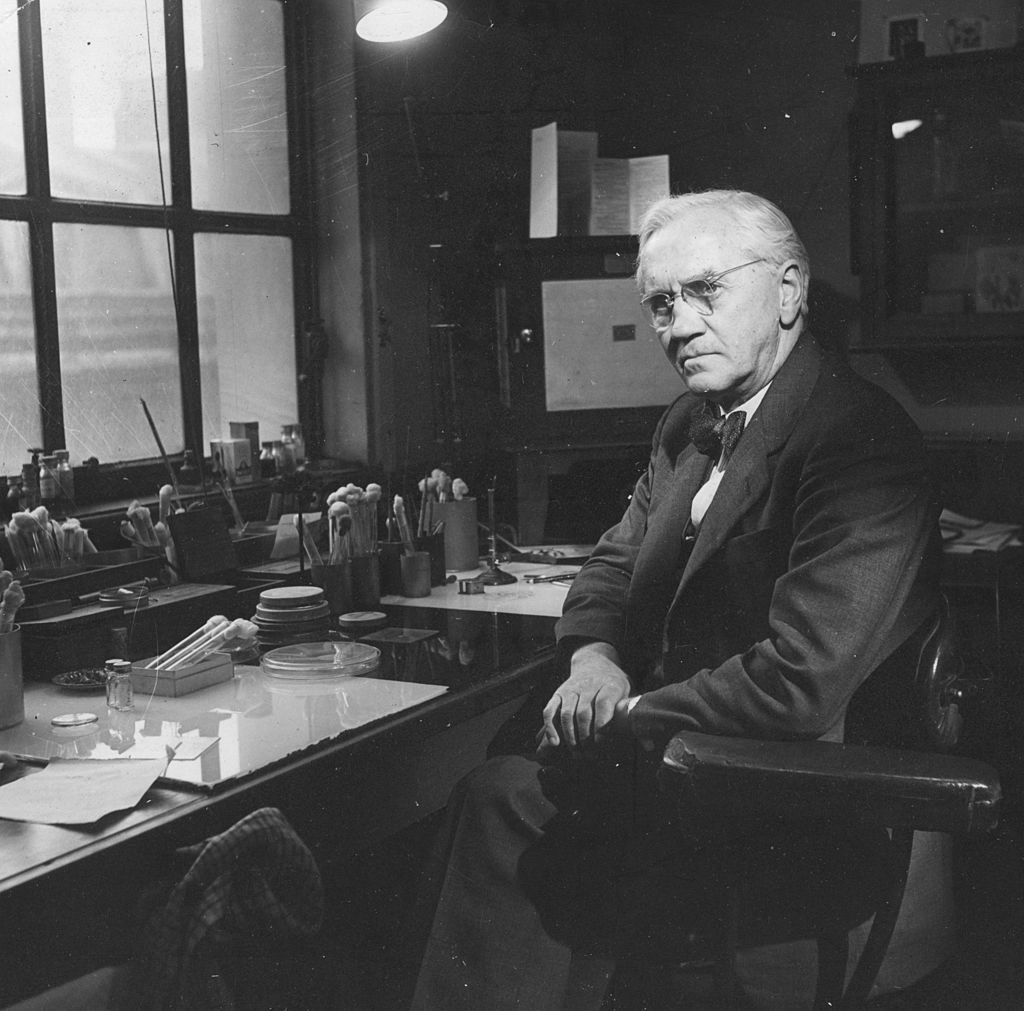

British bacteriologist and Nobel laureate Sir Alexander Fleming in his laboratory at the Wright-Fleming Institute, St. Mary’s Hospital, Paddington in 1951. (Baron/Getty Images)

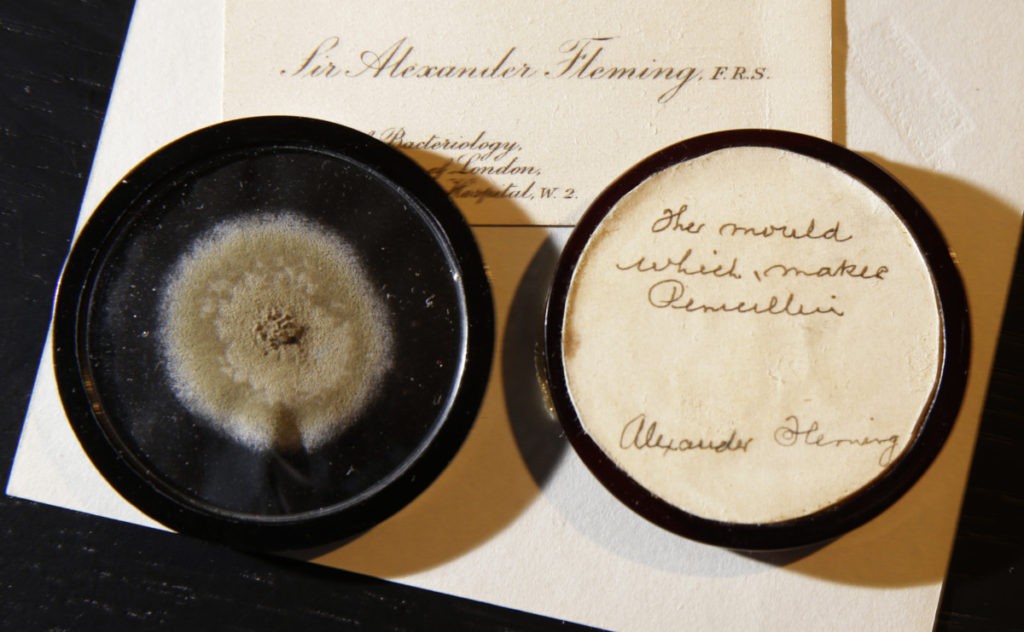

In this photo taken on Thursday, February 16, 2017, a capsule of original penicillin mold from which Alexander Fleming made the drug known as penicillin on view at Bonham’s auction house in London. (Alastair Grant/AP Photo)

In the meantime, Germany, Britain’s once and future enemy, was the world’s leader in life-saving medicines. Going back deep into the 19th century, Germans had been at the vanguard of chemistry and industrial chemicals. And out of that abundance of chemical knowledge, beginning in the early 1930s, they created a whole category of synthetic antibiotics, containing the molecule sulfanilamide. These “sulfa drugs” worked well—and saved many lives.

In fact, had Hitler not been so crazy and warmongering, it’s entirely possible that German synthetics would have continued to be the world’s standard for anti-bacterial medicine.

Yet in 1939, when Hitler started World War Two, the British realized that since they would no longer have access to German medicines, they would need to create them on their own. After all, they knew from past battlefield experience that infections associated with war wounds often killed more soldiers than the wounds themselves.

So now British government officials took a closer look at what Fleming had been trying to accomplish with his natural antibiotic, penicillin. And soon enough, they concluded that the efficacy of the natural antibiotic was, in fact, superior to that of any synthetic antibiotic. (This is not an environmental argument, incidentally, but rather, an empirical argument; the practical scientist has to figure out what kind of medicine works best in any given situation.)

In other words, having been thrown into a sink-or-swim situation by the onset of the war, the British eyed an opportunity to do more than swim—they could build a better boat.

Yet the British also knew that they lacked the industrial capacity to crank out penicillin in the needed quantities—only the Americans had that capacity. Thus in 1940–41, the Brits began collaborating closely with the Yanks, working to develop a joint plan for mass penicillin production. The British were already fighting Nazi Germany, and the Americans figured that soon enough, they, too, would be in the war.

In the words of author Lauren Belfer:

The United States government took over the production, and penicillin was made under the supervision of the same group that was supervising the Manhattan Project for the atomic bomb.

The comrades-in-medicine ended up working together at a U.S. Department of Agriculture laboratory in Peoria, Illinois, where they experimented on ways of accelerating penicillin production. For instance, a USDA official, Dr. Andrew Moyer, figured out that lactose was superior to glucose as a production feedstock.

And superior production was what they got. American penicillin output was essentially zero in 1941, and yet in the first half of 1942, 400 million units had been manufactured. And by 1944, it was abundant enough that all GI’s were issued penicillin in their kits. Indeed, by 1945, Uncle Sam was producing 650 billion units a month.

Using 180,000 units of anti-toxin penicillin and sulpha diazine, members of the U.S. Army Medical Corps treat a German prisoner at an evacuation hospital in Brittany, France, on September 26, 1944 for gas gangrene, which has set in a rifle bullet wound which shattered the patient’s thigh bone above the knee. (George Greb/AP Photo)

Yet to be precise, the government wasn’t producing penicillin at all—it was merely buying it in vast quantities. The actual leaders in production were Merck, E. R. Squibb & Sons, Charles Pfizer & Co., and Lederle Laboratories; these were later joined by Eli Lilly, Abbott Laboratories, Upjohn, and Parke, Davis. In other words, American capitalism was all-in.

So we can see that in a way, it was actually a good thing that the Anglo-Americans no longer had access to German sulfa drugs. Forced to rely on ourselves, we produced a better product—in this case, natural was better than synthetic.

History is like that sometimes: When you have to figure it out for yourself, as opposed to simply relying on the work of others, you often end up doing a better job.

Thanks to penicillin, America’s war-wounded were more likely to survive than Germany’s war-wounded. And that’s one reason why we defeated Hitler in just three-and-a-half years.

Indeed, during the war, we found that different companies were actually working with slightly different strains of penicillin; the cells had simply mutated, spontaneously, in the labs and production sites. This diversity of strains helped give rise to the thousands of different antibiotics that we can use to heal today.

Lessons for Today

In the summarizing words of the University of Utah’s Dr. Roswell Quinn, writing in the March 2013 issue of The American Journal of Public Health, “The U.S. pharmaceutical industry’s involvement in antibiotics originated in a government-sponsored project during World War II.”

Quinn emphasized that “wartime requirements induced scientific collaboration, dramatic acceleration of scientific innovation, and technical standardization.”

As he then detailed, the Pentagon’s Office of Scientific Research and Development coordinated a total of 57 research contracts for preliminary studies of penicillin, as well as clinical trials and other kinds of research. And in the meantime, a second defense agency, the War Production Board—run by William S. Knudsen, cited here at Breitbart News just the other day—worked with 21 companies, five academic groups, and several government agencies to mass-produce penicillin.

All this technical and industrial effort, of course, created a large cadre of trained researchers and skilled production workers—and so even during the war, it was possible to see positive implications for the post-war economy.

In Quinn’s words, the long-term economic benefits were, indeed, profound:

This environment of exchange was profitable and conferred an array of noneconomic assets on industrial participants. Such scientific and technological assets propelled the U.S. pharmaceutical industry beyond previous inefficiencies and transformed it into one of the country’s most successful sectors.

It’s this successful history from the 20th century that Cotton and Gallagher are summoning in the 21st century. As we have seen, once American ingenuity is unleashed, there’s no telling where it will end up.

So it’s little wonder that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs is already noisily upset at the prospect of America reclaiming its health-production sovereignty, tweeting on March 17, “Trying to move medical supply chains back to the US from China is unrealistic and unhelpful. A wrong remedy for #COVID19 pandemic.”

Yes, of course, the Chinese want to keep us weak and dependent on them. Yet with far-seeing leaders such as Cotton and Gallagher on the mission, we won’t let that miserable status quo long continue.

Yes, we have been hit hard by the coronavirus, and yet we all recall that we were hit hard, too, on Pearl Harbor—and we came back for the win in World War Two. And so just as celebrated V.E. (Victory in Europe) Day in 1945, someday we’ll celebrate V.C. Day.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.