“No one knows” if a deradicalisation programme for Islamist inmates and convicted terrorists works, admitted the government’s watchdog for terror laws.

The findings come in a report published on Tuesday by Jonathan Hall QC, the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, which revealed that “no one knows” whether the Desistance and Disengagement Programmes (DDP) are effective at achieving “rehabilitation, reintegration with mainstream society, or long-term deterrence” from radical activity as there is no “systematic evaluation” of the programmes.

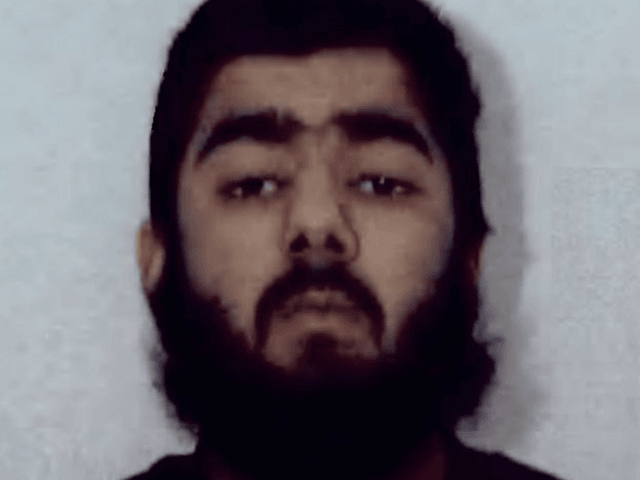

The existence of the DDP, which was established in 2016 and rolled out into prisons in 2018, according to The Times, and deradicalisation programmes in general, came to prominence in 2019 following the Islamist terror attack committed by convicted terrorist Usman Khan in the November of that year in the London Bridge area of the capital.

Khan had attended DDP and was released on licence when he fatally stabbed two people running the Cambridge University-led Learning Together programme, which brings together convicts and criminologists.

Another issue with the programme identified in the report is “engagement”, with many extremists displaying “disruptive behaviour or deliberate disengagement”, which was described as a “significant problem”.

Such examples include pretending to be asleep, wearing earphones, or taking extended toilet breaks. While those out on conditional release are more likely to appear to engage in order to fulfil “a general obligation to ‘be of good behaviour’”, it would be difficult to otherwise enable prosecution for “non-compliance”, the report stated.

Hall also wrote that minors brought to the United Kingdom from Islamic State-held warzones could still pose a potential national security risk, saying: “A difficult cadre of children are those who have returned from Da’esh [Islamic State] controlled areas.

“The fact that many children are brutalised victims, and require rehabilitation, does not mean that they do not present terrorist risk on return and may not have been trained specifically to carry out terrorist acts.”

Naming specifically the London Underground Parsons Green train bomber Ahmed Hassan, Hall wrote that the alleged refugee had “told CT [Counter-Terror] Police in his asylum interview in January 2016 that he had spent three months in an [sic] Da’esh training camp as [a] child, being taught how to kill and being religiously indoctrinated with Da’esh dogma: the trial judge was satisfied that this account was true, although he was not quite as young as he claimed to be.”

The Iraqi had been referred to the government’s anti-terror programme by his teacher over concerns related to his behaviour, where he stated at one time that it was his “duty to hate Britain”, and was seen to have donated money to ISIS. Hassan was about to be given the all-clear by Prevent’s Channel programme shortly before he launched the September 2017 attack.

Mr Hall had admitted in December 2020 that deradicalisation programmes do not always work, comparing extremists to sex offenders who lie to parole boards in order to secure an early release.

Just one month earlier in Vienna, Austria, Islamist terrorist Kujtim Fejzulai had gone on a mass shooting rampage, killing four and injuring 22 others. The ethnic Albanian, who had been imprisoned on terrorism offences, had convinced his parole board that he was no longer a terrorist threat, resulting in early release.

A 2018 study commissioned by the Home Office found that 95 per cent of deradicalisation initiatives were ineffective, and three months after the London Bridge terror attack Prime Minister Boris Johnson stated that “really very few” Islamists can be deradicalised.

“[W]e need to be frank about that, and we need to think about how we handle that in our criminal justice system,” Mr Johnson said in February 2020, emphasising “the custodial option” to protect the public.

That same month, a former al Qaeda terrorist-turned MI6 spy said that he did not believe terrorists could be rehabilitated, saying that the only way authorities could tell if an extremist was reformed would be if they “sung like a canary and provided damaging intelligence on the networks that recruited them”.

Aimen Dean called for longer prison sentences for terrorists, saying bluntly: “If you need another Belmarsh [Prison], build one.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.