Despite coronavirus being significantly less lethal than a pandemic outbreak predicted by top government planners, the UK was still caught unprepared in 2020 in a failure that a parliamentary scrutiny committee categorised as “astonishing”.

Pandemic disease was, by the government’s own reckoning and official advice, the most important civil disaster for which organisations and bodies should prepare. Yet top government ministries — including the Treasury, one of the high offices of state — were caught unprepared by the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak.

A review by parliament’s public accounts committee of the early stages of the British government’s response to coronavirus has highlighted significant gaps in the UK’s response. While the report was largely concerned with the enormous amounts of taxpayers’ money that the government spent in responding to the crisis, a key element of the paper is the ad-hoc nature of that spending. It crucially noted in its conclusion: “We are astonished by the government’s failure to consider in advance how it might deal with the economic impacts of a pandemic.”

The report found that while some departments were well prepared, a major exercise as recently as 2016 to practice readiness for a health emergency did not consider the impact of such an outcome on the economy. The Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy was not even told the exercise was taking place. Because of this lack of preparedness in the Treasury, the government was left creating policy from scratch as lockdown began in March.

Important schemes of support for the economy — including the furlough scheme, one of the most significant interventions by the UK government ever — had never been considered, war-gamed, or pre-planned, and were created on the spot, the report found.

The 20-page paper was also highly critical of the fact the government had no meaningful stockpile of personal protective equipment (PPE), again despite the fact that human pandemic disease — a situation in which PPE is of enormous importance — was recognised by the government itself as the highest priority risk to Britain.

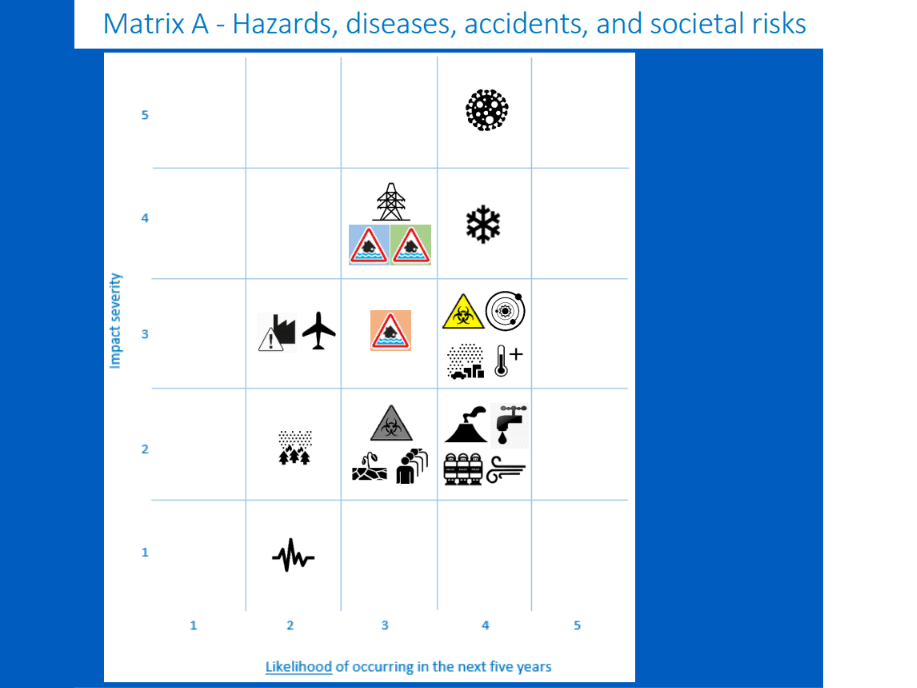

A number of government bodies including the Cabinet Office and the Centre for the Protection of Critical National Infrastructure (CPNI) — an agency that bridges Whitehall and the Security Services — keep what are called risk matrixes which plot potential events according to their likelihood and severity, should they take place. While the government’s own detailed matrixes are not available to the public, significantly simplified versions are released periodically, predominantly to guide businesses in improving readiness.

While the exact placement of different events has varied over the years since these have been made available to the public, some matters remain constant. With the highest relative impact score possible and nearly the highest likelihood score, pandemic disease has always come out as the most urgent matter to address. This compares with “catastrophic terror attacks”, for instance, which have the same impact rating but are much less likely, with their “relative plausibility” being rated as “medium low”.

A UK government risk Matrix. Pandemic disease, represented by the icon of a bacteria, is displayed top right / UK Cabinet Office

Terror attacks on transport systems or public places in the UK, however, have the highest likelihood of all potential hazards, meaning there is a greater than 50 per cent chance of such attacks taking place in a five-year window — as the experience of the past decade has shown time and time again. But their anticipated impact — being very localised — is much lower than a disease outbreak.

The government’s 2008 Risk Register — which makes clear the scale of anticipated disasters and asks large organisations to be prepared for — ironically appearing to fail to do so in some key respects itself. Discussing the Pandemic Influenza outbreak predicted, the document cites between two and 7.5 million dead worldwide, and as many as 750,000 dead in the United Kingdom.

To date, 45,000 people have died with coronavirus in the United Kingdom, compared to 624,000 worldwide, with over 15 million confirmed cases.

Anticipating the reality of 2020, the 2008 document continued: “Normal life is likely to face wider social and economic disruption, significant threats to the continuity of essential services, lower production levels, shortages and distribution difficulties”. But the document reassured the civilian reader, for which it was intended, that the government was actively planning for such an eventuality and was “purchasing and stockpiling appropriate medical countermeasures”.

The 2017 version of the same document again cites those British potential fatality figures. Still, it reassuringly promises: “Government departments, devolved administrations, public health agencies and devolved NHS branches share plans and information… emergency responders have personal protective equipment for severe pandemics and infectious diseases.”

Despite the level of preparedness claimed, and the coronavirus outbreak being — so far — much less fatal than the one planned for, the government nevertheless appears to have been caught short. Similarly, while closing schools in the case of disaster was a known outcome — and businesses were even asked in Risk Registers to consider how they would cope if schools closed and their staff had to go absent to look after their children — the new report found that absolutely no consideration had been made to how the government would support schools while they were closed.

In light of the revelations, the committee has called on the Cabinet Office to review its contingency planning and to ensure that these considerations are passed through the whole of government in future. Unusually for a Westminster report, it also takes a surprisingly anti-globalism line when making recommendations on ensuring there are no future PPE shortages during emergencies. It not only suggests that stockpiles should be made, but that British businesses should be identified that can provide more in a hurry, not relying on foreign supply.

The committee chairman said on Thursday: “Government needs to take honest stock now, learning, and rapidly changing course where necessary. We need reassurance that there is serious thinking behind how to manage a second spike.”

The Guardian reported the government’s response to the paper, which defended itself in terms of the vast volume of money it had made available. The spokesman said: “As the public would expect, we regularly test our pandemic plans – allowing us to rapidly respond to this unprecedented crisis and protect the NHS.

“It was clear that coronavirus would affect all areas of the country, that’s why we immediately put in place an unprecedented initial economic support package for jobs and business worth £160bn. The next stage in our economic response will make a further £30bn available to ensure all areas of the UK bounce back.

“We’re providing over £100m to support children to learn at home, and a £1bn COVID catch-up fund will directly tackle the impact of lost teaching time, as schools and colleges welcome children back in September. In addition, we’ve committed almost £28bn to local areas to support councils, businesses and communities.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.