Efforts to remove a statue of Robert Clive, the great British military commander, from the English market town he represented in Parliament have foundered — at least for now.

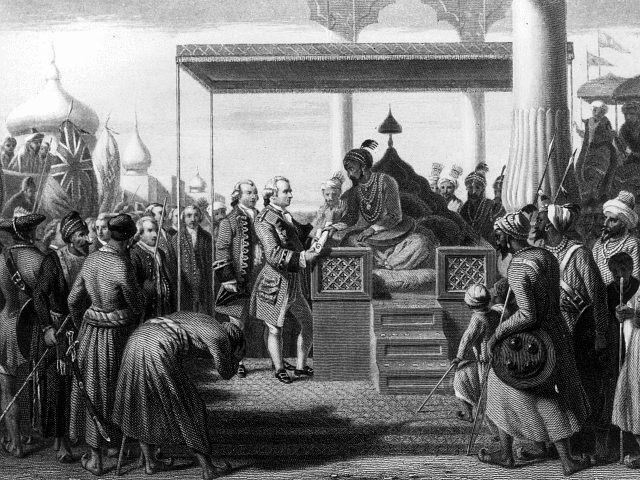

The statue of Clive, remembered by history as Clive of India for leading a small force to victory over the armies of the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey and laying the foundations for Britain’s Indian empire, has had pride of place in Shrewsbury’s town square since 1860 — but activists have been pressing for its removal as a symbol of imperialism and colonialism amid the iconoclastic fervour whipped up by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Conservative-led Shropshire Council has voted 28-17 in favour of taking no action against the statue, however, as reported by the BBC under the loaded headline Clive of India: ‘Demoralising’ decision to keep ‘racist’ statue.

The BBC quoted anti-Clive petitioner Dave Parton as saying he was “shocked” by the failure to tear the statue down: “Only the complete removal of the statue will show the council is serious about racism,” the activist railed.

“Clive will fall, it’s not a matter of if, but when. It beggars belief we have to argue this when his legacy resulted in millions of deaths. It’s quite demoralising, this decision.”

The BBC opted not to quote anyone with an opposing view on Clive, piling on the long-dead national icon elsewhere in the article by claiming he “has faced scathing reviews from some historians” — likely a reference to left-liberal academic William Dalrymple and his allies.

For hundreds of years, however, Clive was acclaimed as one of the great men of British history, despite his flaws.

Indeed, Parliament launched an investigation into his alleged involvement in East India Company misconduct, which was well-acknowledged, in his own lifetime, but was ultimately exonerated and commended for his “great and meritorious service” to Britain.

Historian and journalist Edward Chancellor has noted that when Clive returned to India some time after the military victories which established British ascendancy in the region, it was “to root out corruption among East India Company officials and military officers” — efforts which earned him many enemies — and that his Bengali rival at Plassey had been an unsavoury tyrant denounced even by Dalrymple as a man whose own relatives despised him as a “serial bisexual rapist and psychopath”.

It has also been observed that Clive’s offensive against the Bengali ruler did not come out of a clear blue sky, but was retaliation for the Nawab’s attack on the British factory at Calcutta and murder of dozens of British prisoners by cramming them into a tiny, stifling prison cell — the infamous Black Hole of Calcutta — where they were crushed to death or died of heat exhaustion.

India was also not an independent democratic state when the British arrived there, initially to establish lawful trading factories such as the one at Calcutta, being under the sway of the Muslim Mughals.

The Mughal dynasty, whose waning empire also faced pressure from the French and Dutch, originated from invaders with a lineage stretching back to the descendants of Tamerlane and Genghis Khan, who conquered the region with great violence.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.