“We think Italy may be the most comparable area to the United States at this point,” Vice President Mike Pence told reporters on Wednesday. As Italy’s coronavirus death toll continues to grow many are asking: Why did the virus that originated in Wuhan, China, strike Italy so hard? And why do our leaders think we may become like Italy?

The answer isn’t simple, as there are many variables that go into it, some of which are unique to Italy, while others are less distinctive and thus can offer important lessons for the United States and other nations now enduring their own outbreaks of the pandemic.

Globalism

While the coronavirus outbreak is impacting all of Italy, the disease remains heavily concentrated in Italy’s northern regions, which have direct ties to China.

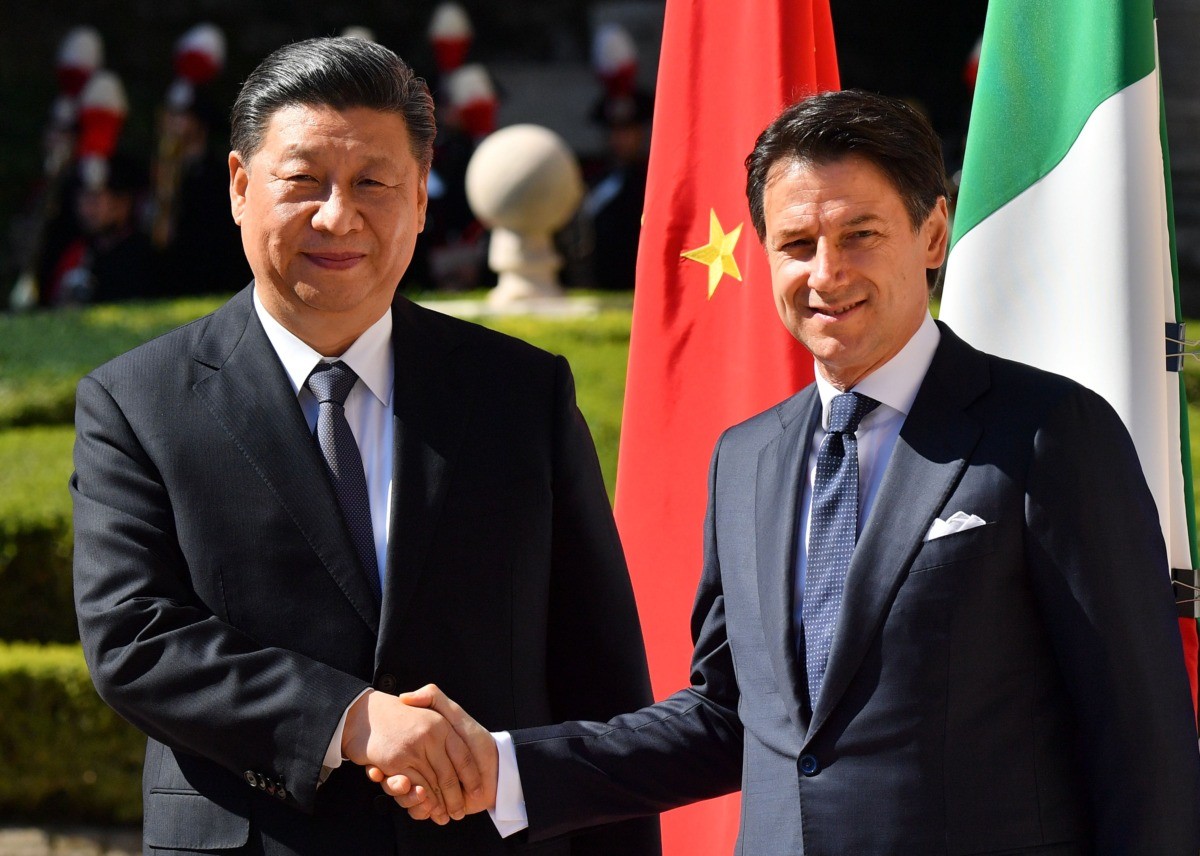

In March 2019, Italy became the first G7 country to agree to join China’s “Belt and Road” (BRI) initiative, a global investment project known as the communist regime’s new “Silk Road,” seeking to link China to Europe and the rest of the world.

The program has since expanded shipping trade in Italy, particularly within the nation’s northern regions, such as Lombardy, the region that is home to Milan, which became the epicenter of the pandemic in Italy.

The first reported cases of the virus in Italy were two Chinese tourists–a husband and wife–who arrived in Milan from Wuhan and fell sick in Rome. The third case was an Italian citizen repatriated from Wuhan. These early cases were quickly isolated in Rome in January. But experts now believe that the virus was spreading for weeks throughout the Lombardy region by the time the 38-year-old super spreader identified as Italy’s “Patient One” contracted the disease in February. Early contact tracing suggests that this individual may have gotten the virus from another European who had recently been to China.

“It spread around Lombardy, the Italian region that has by far the most trade with China and the home of Milan, the country’s most culturally vibrant and business-centered city,” the New York Times reported. But the person they called “Patient One” was probably “Patient 200,” Italian epidemiologist Fabrizio Pregliasco explained.

Italys Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte (R) and China’s Communist Leader Xi Jinping shake hands upon Xi Jinping’s arrival for their meeting at Villa Madama in Rome on March 23, 2019, as part of a two-day visit to Italy. (ALBERTO PIZZOLI/AFP via Getty Images)

By the time Italy finally halted travel from China in February, the virus had already spread throughout the community. Even so, China condemned Italy’s decision.

Political observers now believe that Italy, along with Iran and South Korea — which also have investment ties to China and were among the first nations outside of China to suffer from the coronavirus — delayed initial efforts to contain the virus due to a desire to protect economic ties with the communist regime.

“I didn’t know that there were 100,000 Chinese living in northern Italy, and that many of them come from Wuhan, and that there was a flight between Milan and Wuhan,” said Newt Gingrich, who is in Italy with his wife, Callista, the current U.S. ambassador to the Holy See.

“We think that’s how the virus got to Italy early,” he added. “Initially, the government didn’t realize how dangerous it was going to be. It dealt with it initially as sort of a small town, local, regional problem, and then boom, it exploded.”

“The coronavirus opens a disturbing scenario,” said Andrea Delmastro Delle Vedove, an Italian politician from the national-conservative Fratelli d’Italia party. “It tells us that interdependence on China can be a problem not only from an economic or industrial point of view, but also from a national security, national health prophylaxis.”

Bureaucracy

Another catalyst for Italy’s coronavirus crisis is its slow-moving government, followed by the government’s implementation of partial solutions, which only aided the disease’s proliferation.

When the coronavirus was initially discovered in Italy, many of the nation’s policymakers were skeptical, despite being warned that an epidemic was looming.

“How many people can’t go to work now because of an old man who’s 88 years old, who might have died of the flu?” proclaimed Chamber of Deputies member Vittorio Sgarbi in front of the Italian Parliament in late February, before repeatedly shouting, “This is fiction!”

But then Italy’s own notable politicians started going into quarantine, while others became infected with the disease themselves.

The Italian government began implementing partial solutions by quarantining specific areas, known as “red zones.” Then on March 7, the government quarantined the nation’s entire northern Lombardy region — as well as a few provinces in neighboring regions — which accounted for roughly 16 million of the nation’s population.

Italy’s Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte at a session of Parliament on December 29, 2018, in Rome. (ALBERTO PIZZOLI/AFP via Getty Images)

This move, however, had backfired, as it sparked a mass exodus among Italians native to the south who were temporarily living up north.

So while Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte made his lockdown announcement, swarms of citizens bombarded the train stations — or got into their vehicles — and fled the newly quarantined areas to head home, where they brought the disease to their relatives, further spreading the virus throughout Italy.

Days later, on March 9, the Italian government then applied the same lockdown to the entire country. But some might argue that at that point, it was too late. The damage had already been done.

The Italian government should have locked down the entire nation, rather than initially implement partial solutions, which only facilitated the further spread of the disease throughout Italy.

“Your Prime Minister, on February 3, said publicly: ‘Don’t worry, you don’t have to foresee any pandemic because our system is ready to face any kind of emergency,'” proclaimed governor of Lombardy Attilio Fontana on March 31.

“You were the ones who told me that I was racist when I asked for checks on all citizens who came back from China,” he added. “I was mocked with insolent words.”

Multi-generational Households

When Italians fled the quarantined zones in the north, many of them brought the virus to their relatives in the south. The threat of spread among this densely populated country was especially fatal because Italy has more multi-generational households than any other Western country, and the elderly are at much greater risk of dying from the disease.

Thus, the nation’s love of family tragically created a situation ripe for disaster during this pandemic, as such living arrangements put the elderly at risk of exposure from increased contact with their younger relatives.

“It’s common for grandparents to look after their grandchildren on a daily basis, and for their adult children to look after them, once they become older,” reports Wall Street Journal. “Now, efforts to combat the virus are putting an enormous strain on this social safety net.”

These multi-generational households might help explain why many elderly people in Italy are dying from the coronavirus, according to data collected by the University of Bonn in Germany.

“If you share a house, it’s very likely that other people will get it,” said University of Bonn professor Christian Bayer, who co-authored a new research paper on coronavirus transmission.

The paper discovered a correlation between countries where multi-generational households are common and higher coronavirus fatality rates, reports Wall Street Journal.

Demographics

Italy also has the second-highest elderly population in the world next to Japan. Moreover, the average age of those who die from the disease in Italy is 80. Therefore, an obvious answer as to why Italy’s death toll might be higher than other nations can, in part, be explained by Italy’s large elderly population.

But there’s another factor in place that could explain why so many of Italy’s older coronavirus patients are dying, and it has nothing to do with their age.

Rationing Limited Resources

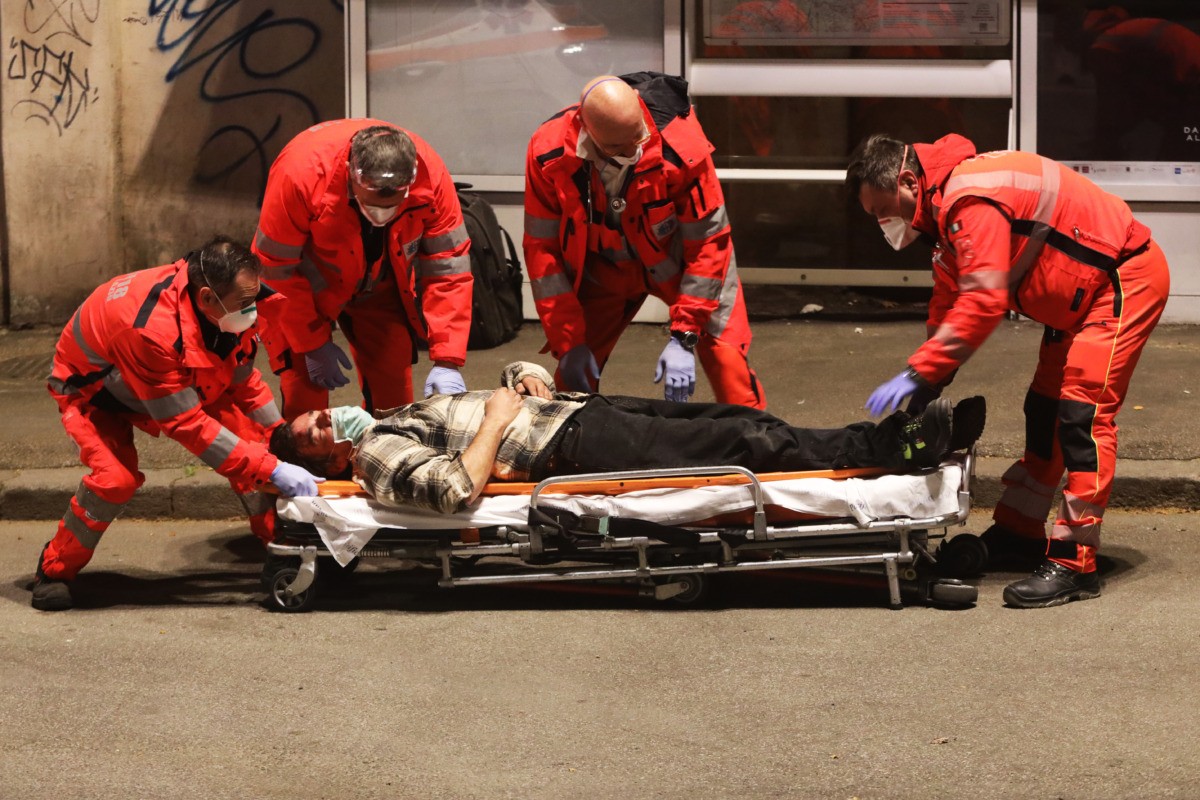

While older patients are dying, the majority of coronavirus patients in Italian hospitals are younger, healthier people — and they’re being prioritized by hospital staff who are forced to overlook older, sicker patients in order to tend to those who are more likely to survive the Wuhan virus.

Among those occupying ICU beds, 12 percent are between the ages of 19 and 50, about 52 percent are between the ages of 51 and 70, and the remainder are over 70. Therefore, roughly 64 percent of coronavirus patients are reportedly under the age of 70.

And the average age of coronavirus patients keeps dropping, as one Italian nurse noted, “the average age has dropped, around 55, 60 years old — 30-year-old males also come in on an oxygen crisis,” reported Il Giornale.

A man wearing a protective mask who was lying unconscious on the ground near a bus stop is carried away by medical personnel from an ambulance, on March 22, 2020, in Rome, Italy, as the spread of the coronavirus persists. (Marco Di Lauro/Getty Images)

The hospital system in northern Italy is one the finest in the country and in Europe. But even so, the coronavirus pandemic quickly overwhelmed the medical resources in this wealthy region of Europe.

With overcrowded hospitals running low on ICU beds, ventilators, and even supplies for their own doctors — many of whom are infected themselves — there are not enough resources to care for everyone.

“We can’t invent new intensive care unit beds,” explained doctor Marco Vergano of San Giovanni Bosco Hospital in Turin.

“It’s important to understand that patients who arrive with a grave interstitial pneumonia from Covid-19 will not be in intensive care for a few days, but for weeks,” he added. That long length of recovery time also strains the medical system in a pandemic when a constant surge of new patients requires care from a diminishing supply of ICU beds.

Meanwhile, Giorgio Gori, the mayor of Bergamo — a city inside of Italy’s worst-infected northern region of Lombardy — said that coronavirus patients who cannot be treated are simply “left to die.”

“If someone between 80 and 95 has serious breathing difficulties, you probably don’t proceed,” added Christian Salaroli, a doctor at a hospital in Bergamo.

A medical worker wearing a face make and protection gear tends to a patient inside the new coronavirus intensive care unit of the Brescia Poliambulanza hospital, Lombardy, on March 17, 2020. (PIERO CRUCIATTI/AFP via Getty Images)

Doctors treat COVID-19 patients in an intensive care unit on March 26, 2020, in Rome, Italy. (Antonio Masiello/Getty Images)

While Italy’s northern hospitals are overwhelmed — and as the disease begins to creep south — politicians south of Lombardy warn that their healthcare facilities will also be unable to fully assist older patients.

“Soon, we will no longer be able to help our most fragile citizens,” said Valeria Mancinelli, the mayor of Ancona, a city located in Italy’s Marche region, closer to Rome.

Marco Pavesi, a doctor at the Policlinico San Donato hospital in Milan, noted last week in an op-ed for the New York Times that if the number of coronavirus patients does not decrease, he could envision a scenario in which “triaging patients” becomes “standard practice.”

“Our elders, sick and left alone by the state. That’s why there are so many deaths in Lombardy,” reported La Repubblica.

Death Tolls Cannot Be Accurately Compared Between Nations

It is difficult to compare the death toll for coronavirus between nations because some nations are clearly falsifying evidence. Take China, for example, the nation that lied to the world about the coronavirus from the beginning. Should we believe the communist regime when it tells us that a little over 3,000 people died from the disease before the fatalities magically began tapering off?

There is increasing evidence that China downplayed its coronavirus death toll by tens of thousands (and perhaps even millions).

Then there’s Iran, which denies that it has mass graves dug for coronavirus victims, despite the reality that the graves are so enormous, they are visible from space.

As for nations that are more transparent with their data — such as France and Germany — each country has different ways in which it records data, making these statistics inconsistent across the West.

“The way in which we code deaths in our country is very generous in the sense that all the people who die in hospitals with the coronavirus are deemed to be dying of the coronavirus,” said professor Walter Ricciardi, the scientific adviser to Italy’s minister of health, according to the Telegraph.

This means that if someone dies with coronavirus in Italy, they are recorded as a coronavirus fatality.

Italian flags fly at half-mast on the Altare della Patria – Vittorio Emanuele II monument in Rome on March 31, 2020, as flags are being flown at half-mast in cities across Italy to commemorate the victims of the virus, during the country’s lockdown aimed at curbing the spread of the COVID-19 infection (VINCENZO PINTO/AFP via Getty Images)

But other nations might say, “Well, this person died with coronavirus, but they had these other pre-existing conditions, which could have been the main factor.” And then the death will not be recorded as a coronavirus fatality.

The same could be said for how countries define “pre-existing conditions.” Italy might be too generous in that department as well.

For example, a recent Italian study revealed that more than 99 percent of Italy’s coronavirus deaths have been people who had some type of pre-existing medical condition.

But when you break down what Italy considers a “pre-existing condition,” you come to find that the definition includes high blood pressure (which nearly half of Americans have), and diabetes (which roughly one in every three Americans have), according to the CDC.

Moreover, among those who have died from the Wuhan virus in Italy, more than 76 percent had high blood pressure and more than 35 percent had diabetes.

Conditions like obesity, however, didn’t even make it onto Italy’s short list of pre-existing conditions for coronavirus fatalities, and we know this condition has been a factor in coronavirus deaths elsewhere.

Take Louisiana for example, where diabetes and obesity are much more prevalent. So far, the coronavirus has been deadlier in New Orleans than it has been in the rest of the U.S., as it has a per-capita death rate significantly higher than New York City, reported Reuters on Thursday, adding that data suggests that the greater prevalence of obesity in New Orleans is a contributing factor.

“Some 97% of those killed by COVID-19 in Louisiana had a preexisting condition, according to the state health department. Diabetes was seen in 40% of the deaths, obesity in 25%, chronic kidney disease in 23% and cardiac problems in 21%,” reported Reuters.

So while Italy’s death toll might have been compounded by its large elderly population, other nations will face their own challenges due to a greater percentage of their population suffering from one or more of the pre-existing conditions that can make the virus more deadly — conditions that range from high blood pressure to diabetes, lung disease, asthma, or just obesity.

But despite all of that, it’s still too early to make comparisons across countries, as the pandemic hasn’t run its course yet, and experts believe that other nations — such as the United States, England, and France — are 9 to 10 days behind Italy with regards to coronavirus progression.

Meanwhile, Spain is bracing itself to become the next Italy, as the nation exceeded 10,000 coronavirus-related deaths on Thursday — a statistic that Italy had suffered one week ago.

A woman wearing a face mask arrives at the South Municipal cemetery in Madrid, on March 23, 2020, to attend the burial of a man who died of the new coronavirus in Spain, one of the pandemic’s worst-hit countries after China and Italy. (BALDESCA SAMPER/AFP via Getty Images)

Italy’s Death Toll May Actually Be Higher Than Reported

Speaking of the different ways in which countries record data, countries have different ways in which they test for the coronavirus as well.

While Italy initially conducted coronavirus testing among both symptomatic and asymptomatic contacts of people, stricter testing policies were implemented on February 25, according to a paper published in the peer-review journal JAMA.

This means that Italy’s fatality rate could actually be lower than reported, as the nation does not have a good indication of how many mild or asymptomatic cases are out there, given that Italy’s new policies prioritize testing for people with severe symptoms and limit testing for people who are asymptomatic or with mild symptoms.

This also means that Italy’s death toll could be higher than reported, as the country does not have a good indication of how many people have died from the coronavirus at home, without ever being tested for the disease.

So while some may prefer to downplay this pandemic, there is the undeniable evidence of the plethora of coffins leaving Bergamo every day, and the lonely funerals — due to loved ones of the deceased being on lockdown — held every half hour now.

And it took only a matter of weeks for this reality to transpire.

Local newspaper Eco di Bergamo features several pages of obituaries in its March 17, 2020. Bergamo is at the heart of the hardest-hit region in Italy’s coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

Parish priest of Seriate, Don Mario stands by one of the coffins stored into the church of San Giuseppe in Seriate, near Bergamo, Lombardy, on March 26, 2020, during the country’s lockdown following the COVID-19 new coronavirus pandemic. (PIERO CRUCIATTI/AFP via Getty Images)

The coffins of deceased coronavirus victims are stored in a warehouse in Ponte San Pietro, near Bergamo, Lombardy, on March 26, 2020, prior to being transported in another region to be cremated. (PIERO CRUCIATTI/AFP via Getty Images)

A convoy of Italian Army trucks arrives from Bergamo carrying bodies of coronavirus victims to the cemetery of Ferrara, Italy, where they will be cremated, Saturday, March 21, 2020. The transfer was made necessary since Bergamo mortuary reached maximum capacity. (Massimo Paolone/LaPresse via AP)

A priest celebrates funeral service without relatives for a coronavirus victim inside the cemetery of Zogno, near Bergamo, northern Italy, on March 21, 2020. (PIERO CRUCIATTI/AFP via Getty Images)

Italy’s struggle with the Chinese coronavirus offers a glimpse of what other nations could face if they do not adequately plan to combat the disease.

Thus, we should examine other countries, and not disregard their hardships — because if we don’t prepare and the virus hits us hard, then the added insult to injury will be that we should have known better.

You can follow Alana Mastrangelo on Twitter at @ARmastrangelo, and on Instagram.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.