A controversial review into the state of Sharia law in the United Kingdom and the bodies administering it has revealed the British government to be unaware of exactly how many of the Islamic law councils are operating in the country, an admission of systemic discrimination against women, including the victim of forced marriage being asked to appear alongside her family, with an “inappropriate” adoption of civil legal terms used.

The document — entitled ‘The independent review into the application of sharia law in England and Wales’ — was criticised for taking a theological approach to the issue after Islamic theologian Mona Siddique OBE, as well as Imam Qari Muhammad Asim MBE and Imam Sayed Ali Abbas Razawi, were appointed to the panel and advisory board. Other members included Sam Momtaz QC, Anne-Marie Hutchinson OBE QC (Hon), and Sir Mark Hedley DL.

Described as having an “inappropriate theological approach” by women’s rights groups, the report recommends the recognition of Islamic marriage in civil law, and vice versa, so that Muslim women do not necessarily feel their only option for divorce is through Sharia councils. The sole focus of the report appears to be divorce, despite an admission that a smaller amount of Sharia councils’ works are not in this area.

The report stunningly admits:

The exact number of sharia councils operating in England and Wales is unknown. Academic and anecdotal estimates vary from 30 to 85. The review has identified 10 councils operating with an online presence. The sharia councils identified by the review were mostly in urban centres with significant Muslim populations, such as London, Birmingham, Bradford and Dewsbury.

The investigators also concede they were not actually privy to any Sharia council processes and did not witness their active work:

The review panel did not observe first hand either the councils’ process for obtaining information from the individuals seeking their assistance or the decision-making process used by the councils.

There was — as the report’s methodology states — a public call for evidence on July 4th, 2016, with closed, oral evidence sessions with users of Sharia councils, women’s rights groups, academics, and lawyers, as well as other interested parties.

One of the primary recommendations of the investigation is the idea of “linking Islamic marriage to civil marriage” to ensure “that a greater number of women will have the full protection afforded to them in family law and they will face less discriminatory practices. This will be a positive move aimed at giving women maximum rights should the marriage end in divorce”.

This would require alterations to the Marriage Act 1949 and the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, “to ensure that civil marriages are conducted before or at the same time as the Islamic marriage ceremony, bringing Islamic marriage in line with Christian and Jewish marriage in the eyes of the law”.

Despite numerous admissions that men have an upper hand in Sharia councils, the report concludes the system should not only remain in place, but should be self-regulated by imams:

-

It could invite, encourage or even urge sharia councils to adopt a system of uniform self-regulation.

-

The state could provide a system of regulation for sharia councils to adopt and then to self-regulate.

-

It could impose such a system and provide an enforcement agency similar to OFSTED. However, proportionality is not the only issue. Just as the state does not confer legitimacy on the Beth Din or on Catholic tribunals by seeking to regulate them, the state may be reluctant to regulate sharia councils. That raises a dilemma: either the state withholds further intervention or it risks intervention being perceived as conferring legitimacy upon sharia councils and thereby creating a parallel legal system.

Despite the difficulties, we have concluded that intervention/regulation carries more advantage than no intervention.

Men are revealed to have an advantage in Sharia councils because of the ease of routes to divorce offered to them ahead of women. The report appears to want to ease this problem, rather than eradicate it, and lend the legitimacy of the British state to Sharia law.

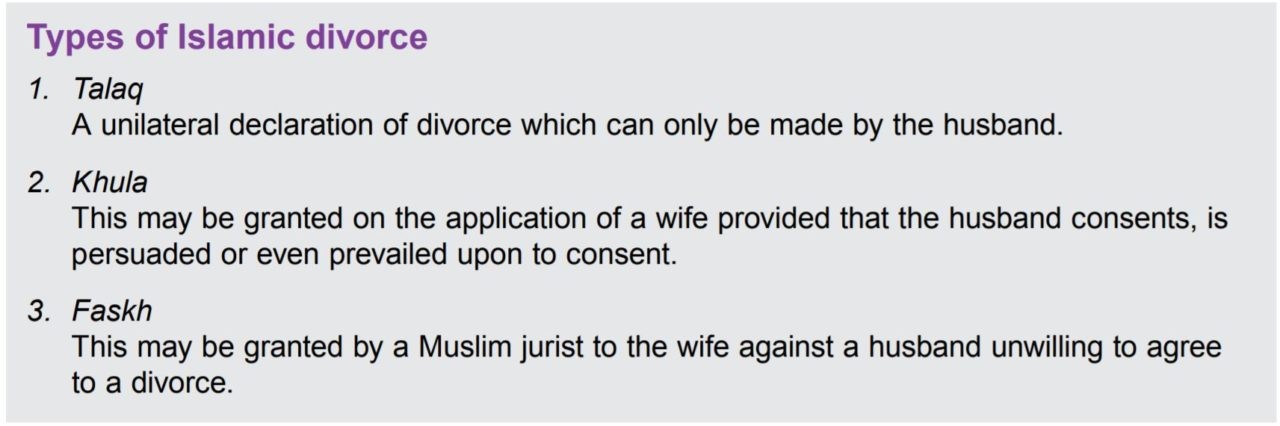

Men seeking an Islamic divorce have the option of ‘talaq’, a form of unilateral divorce that they can issue themselves. Women do not have this option, unless inserted as a term in the marriage contract (which varies from school to school) and therefore have to seek a ‘khula’ or ‘faskh’ from a sharia council.

The review also heard evidence “that in some instances, during khula divorces, women were asked to make some financial concessions to their husband in order to secure the divorce”.

Rather than a condemnation of such practices, the review seeks to create “a body by the state with a code of practice for sharia councils to accept and implement. This body would include both sharia council panel members and specialist family lawyers. This body could go on to monitor and audit compliance of the code of practice.”

The report also contains an unassailable admission — historically rejected or even ridiculed by left-wing politicians and campaigners — that “[t]he primary and underlying principle of sharia councils is the application of sharia law”, and that this is indeed taking place in Britain, and to an extent that the government is unaware.

The most well established sharia councils in England and Wales have been in existence since the 1980s. Anecdotal evidence indicates that the numbers of sharia councils in England and Wales has increased in the last 10 years.

The review also wrestles with the idea of [in effect giving] a quasi-legal status to the councils:

Such regulation will indeed endorse and add legitimacy to the perception of the existence of a parallel legal system whilst the outcomes of the sharia council processes in terms of religious divorces have no standing in civil law.

Another problem arising from such an endorsement is the fact the review revealed a misinterpretation of British law:

The sharia councils that were visited all had a very loose definition of mediation. In all cases there appeared to be confusion between mediation and what is in effect reconciliation counselling. All councils visited within the context of the review made provision for reconciliation counselling at the commencement of the process. The reconciliation was invariably described as ‘mediation’ when it is clearly not.

Save for one individual, the review found that those conducting the mediation at sharia councils have not received mainstream training from the recognised mediation organisations, nor was there any evidence of accreditation. The sharia councils appear to use the term mediation in a much looser sense than that of the highly trained and accredited mediators practicing in family law.

The authors add:

The creation of state endorsed regulation sends the message that certain groups have separate and distinct needs and further that sharia councils are an appropriate forum for resolution of their family law disputes. In short it would perpetuate the myth of separateness of certain groups. The acceptance of the premise that sharia councils only deal with, engage in or touch upon the dissolution of the religious marriage aspect of the dispute is naïve and unrealistic. In any family law or relationship dispute the issues are multi-faceted. Ancillary outcomes which arise out of the ‘mediation and other functions’ that sharia councils undoubtedly perform may be given legitimacy. Those functions where they deal with dowry forfeiture (or return) financial remedies, arrangements for children and issues regarding future behaviour and conduct will impact on the civil rights of those to whom they relate.

While the report praised some “good practice” in the Sharia councils, these are arguably overshadowed by the “bad practice” revelations.

Examples of “good practice” according to the authors included:

- reporting of family violence and child protection issues to the police;

- women unable to pay fees have them lowered/no payment taken;

- religious divorce granted as formality upon civil divorce;

- councils’ signposting to civil remedies, such as civil courts for child arrangements;

- little evidence of women being asked to reconcile relationships rather than obtain divorce;

- councils declining to deal with any ancillary issues and referring users to civil courts;

- in practically every case where a woman was seeking divorce, a divorce was granted;

- some councils had women panel members;

- some councils said they have safeguarding policies in relation to children and domestic violence.

Evidence of bad practice however included:

- inappropriate and unnecessary questioning in regards to personal relationship matters;

- a forced marriage victim was asked to attend the sharia council at the same time as her family;

- insistence on any form of mediation as a necessary preliminary;

- women being invited to make concessions to their husbands in order to secure a divorce (men are never asked to make these concessions). For example in khula agreements, husbands may demand excessive financial concessions from the wife;

- lengthy process so that while divorces are very rarely refused they can be drawn out;

- inconsistency across council decisions and processes;

- no safeguarding policies and/or the recognition for the need of safeguarding policies;

- no clear signposting to the legal options available for civil divorce;

- even with a decree absolute a religious divorce is not always a straightforward process and the council will consider all the evidence again;

- adopting civil legal terms inappropriately, leading to confusion for applicants over the legality of council decisions;

- very few women as panel members;

- panel members sitting on sharia councils who have only recently moved to the UK, and who do not have the required language skills and/or wider understanding of UK society;

- varying and conflicting interpretations of Islamic law which may lead to inconsistencies.

Addressing the calls to ban Sharia in the UK, the authors note (emphasis added): “Th[e] demand [for Sharia councils] will not end if the sharia councils are banned and closed down and could lead to councils going ‘underground’, making it even harder to ensure good practice and the prospect of discriminatory practices and greater financial costs more likely and harder to detect. It could also result in women needing to travel overseas to obtain divorces, putting themselves at further risk. We consider the closure of sharia councils is not a viable option. However, given the recommendations also proposed in this report include the registration of all Islamic marriages as well as awareness campaigns it is hoped that the demand for religious divorces from sharia councils will gradually reduce over time.”

Critics from across the political spectrum noted of the review: “It is evident from the limited terms of reference and the makeup of the review panel that the review is in danger of becoming seriously compromised and as such, we fear that it will command little or no confidence”, citing the make-up of the panel:

Although some of those appointed to the panel come from judicial and family/ children law backgrounds, two Islamic ‘scholars’ have been appointed as advisers to the chair, Mona Siddiqui who is herself a theologian. This is cause for alarm: the government has constituted a panel more suited to a discussion of theology than one which serves the needs of victims and is capable of investigating the full range of harms caused by sharia councils and tribunals, particularly for women.

They called for the government to “[d]rop the inappropriate theological approach, and appoint experts with knowledge of women’s human rights, those who can properly and independently examine how sharia systems of arbitration in family matters contravene key human rights principles of equality before the law, duty of care, due diligence and the rule of law. The inquiry must be clearly framed as a human rights investigation not a theological one.”

Supporters of the review included Iman Abou Atta — a director at the discredited TellMAMA group that seeks to shut down criticism of Islam, as well as Labour Party councillor Neghat Khan, the extremist-linked East London mosque’s manager Sufia Alam, and Guardian journalist Alia Waheed.

Raheem Kassam is the editor in chief of Breitbart London and author of the bestselling book No Go Zones: How Sharia Law is Coming to a Neighborhood Near You

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.