AFP — It’s a snapshot from another political era. Forty-one years ago, in Britain’s last referendum on Europe, Margaret Thatcher hit the campaign trail clad in a woolly jumper emblazoned with a Union flag.

But the 1975 poll, which saw Britain embrace membership of what was then the Common Market, has plenty in common with the current bitter and closely-fought debate.

It also carries lessons for politicians ahead of the June 23 vote on whether to stay in or leave the European Union — not least that the referendum may not resolve the issue for long.

Labour prime minister Harold Wilson called the referendum on June 5, 1975, as a way of trying to appease the eurosceptic wing of his fractured party, and urged Britons to stay in after securing concessions from Brussels.

This time around, it is Conservative premier David Cameron who is holding a vote to try to heal party splits, and who is campaigning to “Remain” on the basis of a renegotiated EU settlement.

For Tim Bale, politics professor at Queen Mary, University of London, the lesson of the past is that a referendum cannot guarantee to put a contentious matter to rest.

“It will fail utterly to settle the Europe question ‘once and for all’,” Bale wrote in a blog post.

“As to whether, in a democracy, that kind of never-ending uncertainty is necessarily a bad thing, who knows?” he said.

Wilson secured 67 percent support for staying in the European Economic Community (EEC), which Britain had joined two years earlier — a result Cameron would be very happy with.

Opinion polls currently show the race is close, although the “Remain” camp has a slender lead.

Back then, the left wing of Wilson’s Labour party wanted to leave the Common Market, among them current leader Jeremy Corbyn — who now advocates staying in.

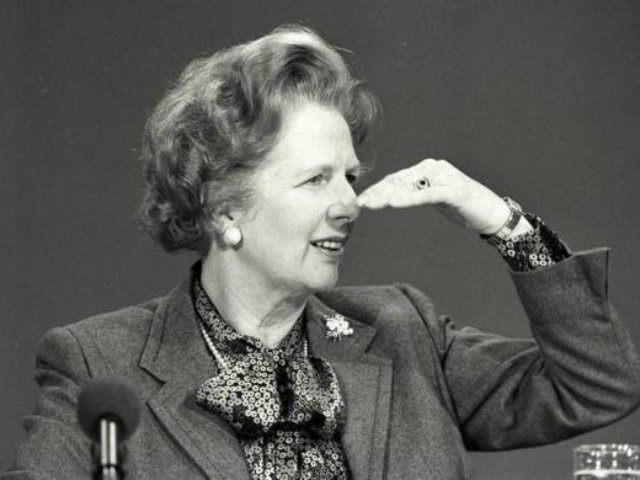

Meanwhile Thatcher, newly elected as leader of the opposition Conservatives, strongly defended British membership of the EEC, saying the country was “inextricably” part of Europe.

She would later become a heroine to Conservative eurosceptics due to her visceral declarations of opposition to Brussels when she became prime minister.

– ‘Not what we voted for’ –

Many older Britons who want to leave the EU argue that today’s bloc is not the same entity as the EEC they supported joining in 1975.

“When we voted in the Common Market, this isn’t what we voted for,” Lynn Everett, 62, who runs a football merchandise stall in Birmingham, told AFP last week.

“I voted in. It was a totally different thing. If we don’t leave this time, I’m finished with politics.”

The Brussels landscape has changed in the last four decades as economic union has evolved into stronger political ties, although Britain has not joined the single currency, the euro.

The EEC had six founding members and membership had risen to nine by 1975. The present-day EU has grown to 28 members, with others knocking on its door.

The end of the Cold War in 1991 and the lifting of the Iron Curtain paved the way for eastern European countries like Poland and Hungary to join in 2004.

The free movement of EU citizens means many thousands of eastern Europeans have since come to Britain to seek employment, with no need for a work permit.

Over three million people born in other EU countries are now thought to live in Britain and immigration is one of the most controversial issues in the current referendum.

Cameron argues that Britain’s economy benefits from EU migrants who work and pay taxes.

But he has pledged to restrict welfare payments to some migrants under a renegotiated membership deal with Brussels.

Amid such a complex and changing picture, some argue that the premier faces a more difficult task than Wilson did in 1975.

“In many ways, the stakes of voting on EU membership are higher now than in 1975,” wrote David Thackeray, a politics lecturer at Exeter University, in a blog post.

“Convincing voters to support the renegotiation terms may also be harder”.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.